A Reality Check on Our "National Reality Crisis"

Is it time for a Kerner Commission-style report on disinformation? Or would it just add more fuel to the politics of resentment?

Do we need a “reality czar”? Are we in the midst of a “national reality crisis”? That’s the view of longtime New York Times technology columnist Kevin Roose, who wrote an essay a week ago titled, “How the Biden Administration Can Help Solve Our Reality Crisis.” In it, he makes several interconnected arguments.

First, the extent of delusive political beliefs about conspiracies like QAnon and the election result is far greater than other hoaxes, lies and prejudices that have captured hearts and minds in the past.

Second, that widespread belief in an alternate version of reality is making it harder to deal with challenges like the pandemic or climate change.

And third, and most serious, “unless the Biden administration treats conspiracy theories and disinformation as the urgent threats they are, our parallel universes will only drift further apart, and the potential for violent unrest and civic dysfunction will only grow,” Roose writes. [italics added.]

From these concerns, Roose spins up a need for a national “reality czar” who would head up a cross-agency task force to tackle disinformation and domestic extremism, and act as “the tip of the spear for the federal government’s response to the reality crisis.”

In a similar vein, Bill Adair, the founding editor of Politifact and Philip Napoli, a Stanford public policy professor, recently wrote in The Hill that President Biden should create a bipartisan commission to investigate the problem of misinformation and make recommendations on how to address it, modeled on the 1967 Kerner Commission. They argue:

“The mob that stormed the building was acting on a tidal wave of misinformation about the election that was spread by the president, his fellow Republicans and their supporters using a web of partisan media outlets, social media and the dark corners of the internet. The lies flourished despite an extraordinary amount of debunking by fact-checkers and Washington journalists. But that fact-checking didn’t persuade the mob that stormed the Capitol — nor did it dissuade millions of other supporters of the president. Fed a steady diet of repetitive falsehoods by elected officials and partisan outlets, they believed the lies so much that they were driven to violence.”

Presaging a possible federal commission, the Aspen Institute is launching a new commission “to examine the nation’s public information crisis,” installing Christopher Krebs, the former director of the Department of Homeland Security’s Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, who was fired by Trump for telling the truth about election fraud, as its chair.

There are some good ideas here. Federal agencies that are dealing with COVID-related conspiracy theories, like the Centers for Disease Control, ought to interface with other agencies dealing with cyber-security challenges, because foreign actors do want to exploit internal cleavages in American society to our overall detriment. And legislators and regulators need to be pressing the tech platforms for more transparency into their algorithms and how they may accentuate emotional engagement and filter bubbles. The FTC could be doing a lot more to ensure that consumers aren’t being harmed by targeted advertising filled with misinformation.

But a “reality czar” is a terrible idea. And a national commission on misinformation risks fundamentally misunderstanding the situation we’re in.

It’s not just, as libertarian Matt Welch of Reason magazine argues, that “Proposed changes to government policy should always be visualized with the opposing team in charge of implementation.” I agree, a President Ted Cruz or President Tucker Carlson anointing a “reality czar” would be a very bad development.

First of all, as investigative journalism legend I.F. Stone often said, “all governments lie.” Vesting the power to determine the objective truth of debated issues in a central authority is not only dangerous, it’s doomed to fail. A “reality czar” would have an impossible job.

Besides, skepticism about political claims is a good thing. We are better off living in a country with an oversupply of skepticism about government authority than one where everyone dutifully conforms to what the government mandates. When government needs the public to take some action—like wearing masks to minimize the spread of COVID-19—it should make that case using persuasion, and using existing authority that elected legislatures have already given to governors and public health agencies.

But, you may be shaking your head, we’re in a crisis! One-third of Republicans have a favorable view of QAnon! More than 70% of Republicans believe Trump won the election! These are worrisome numbers, but let’s put them into context.

Has there ever been a time when sizable minorities of Americans didn’t believe some kind of nonsense? A little more than a third of Americans surveyed in 2016 said they believed (completely or at least partially) the “chemtrails” conspiracy theory, which holds that airplanes are spraying toxic chemicals into the air, to do things like change the weather or control our minds. A 2006 poll found that one-third of the public believed that “federal officials either participated in the attacks on the World Trade Center or took no action to stop them.”

Well, take a deep breath and consider. Have government officials allowed toxic chemicals to be sprayed in ways that have harmed Americans? Yes, just look up the history of DDT. And while there’s no evidence that government officials participated in the 9-11 attacks, was President Bush warned in advance, and did he fail to take that warning seriously? Yes, just read the 9-11 Commission Report, which cites the President’s Daily Brief of August 6, 2001, titled “Bin Ladin Determined to Strike in the US.”

My point is that we should be really, really careful how we interpret polls that seem to suggest that huge blocs of Americans hold solid opinions that we can clearly distinguish in a sentence. I may turn out to be wrong, but I think the salience of the QAnon world-view as well as the Republican disbelief in the election result is smaller than we think and likely to go down as Trump is no longer in office and in command of the White House bully pulpit. As this piece in Nature suggests, we may have just passed Peak Paranoia.

Support for QAnon or the Big Lie that the election was stolen is worrying, but the number of people taking action as a result of these beliefs is quite small. The January 6th Stop the Steal rally, which turned into the mob assault on the Capitol, was attended by perhaps 8,000 people. About 800 broke into the building, according to federal authorities investigating the event. The impeachment trial of President Trump, which begins today, will re-amplify the actions of these people, and indeed it should—because the political ramifications of Republican elected officials condoning Trump’s lies are important. But in a country of 330 million, a few thousand people willing to storm government buildings because they think Democrats are pedophiles who stole the election from Trump is not a national “reality crisis” – it’s a law enforcement problem.

And having spent a lot of time talking to political outsiders over the years, it’s my sense that the embrace of misinformation is a symptom of a deeper problem: an ongoing battle for status and recognition playing out across America as we become a more multiracial and multicultural nation. In the case of resistance to the facts on the pandemic, vaccines or climate change, the core cleavage is between rural and urban dwellers. Katherine Cramer, a political scientist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, captured this issue well in her 2016 book The Politics of Resentment: Rural Consciousness in Wisconsin and the Rise of Scott Walker. Instead of determining their political identity by what you might call “economic self-interest,” a lot of Americans place resentment of other citizens at the center of how they think about politics.

If people are consuming a lot of misinformation about COVID-19 or the election, it’s because it validates a status need they have, to be seen as equal to or smarter than or better than those “liberal elites” who keep telling them they’re dumb or backwards and need to trust the experts. We won’t weaken that phenomenon one iota with a national commission on disinformation. Nor will we reduce some politicians’ need to placate those views (or desire to play them up for their own gain) by holding a fancy Aspen Institute event.

Let’s not confuse the political crisis we are in for a “reality crisis.” And maybe, let’s also consider how the priorities of funders and the quirks of the US tax code (which privilege donations to nonprofits over political organizers) may be skewing how we understand the situation we’re in. As Bill Adair and Philip Napoli noted in passing in their Hill oped, “For the past four years, academics and journalists and philanthropists and foundations and tech leaders have thrown a lot at the problem of misinformation — hundreds of millions of dollars and millions of words, plus countless conferences and reports — and yet the problem seems worse than ever.” [Emphasis added.]

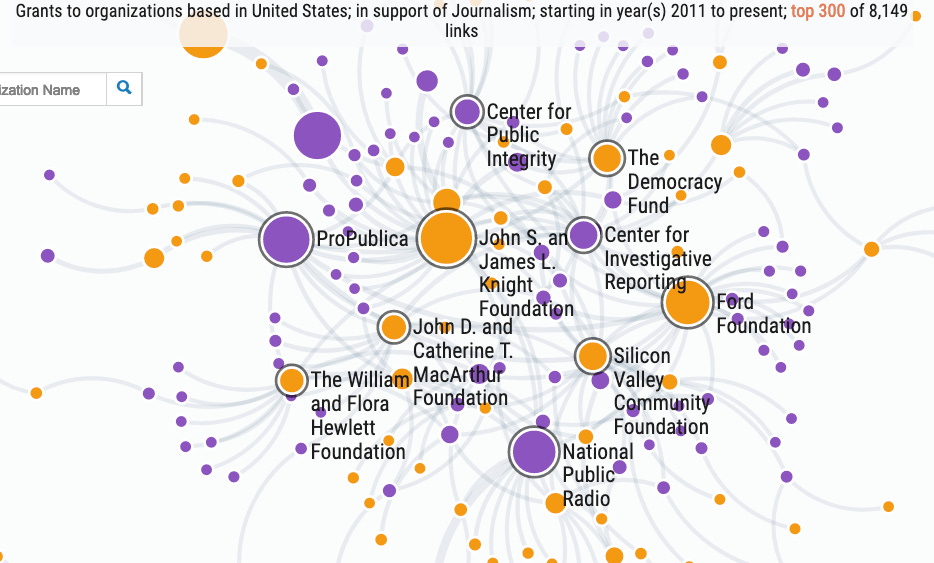

Indeed they have. Since 2011, American foundations and other grantmakers have given nearly $1.3 billion to support journalism, according to data collected from annual IRS 990 filings by the Foundation Center. Since those filings are generally made public two years late, I’ve left out the data for 2019 and 2020, but I’m willing to bet the trend line didn’t change. In the two years after Trump got elected, there was a boom in giving to the sector, with nearly a half billion flowing to academic centers, investigative journalism hubs, nonprofit news startups, and assorted convenings. (The Center’s database doesn’t include donations from Craig Newmark’s philanthropies—who I should note has been a big supporter of my work over the years—so if anything the picture understates how much the sector has blown up.)

From my perch at Civic Hall, I saw a lot of this money slosh into the journalism sector, and indeed the number of conferences and reports mushroomed. I vividly remember attending one such summit held in April 2019 at the offices of TED in New York City, where Clair Wardle of First Draft (a group that has done excellent work on disinformation) opened the meeting by saying, “We can't keep having meetings and then asking for funding, having meetings and asking for funding. We need concrete interventions and a road map for the next 3-6 months.”

In my humble opinion, we need to look elsewhere. First, as Roose argues at the conclusion of his column, concrete improvements in people’s lives will mean much more than any change in how the tech platforms police themselves or how government agencies share information with each other about emerging hoaxes. Investing in developing the political muscle to win those kinds of changes—something I harp on a lot in this newsletter—would help a lot. And second, we need more ways of showing we’re listening, not just that we’re talking, if we are ever going to reduce the intensity of the politics of resentment. Our political system and our media system don’t model listening very well, and the incentives for just making your base feel good right now outweigh any incentives for showing that you are listening too. A starting point might be in efforts that “complicate the narrative,” as outlined in this 2018 essay by Amanda Ripley the Solutions Journalism Project.

Odds and Ends

-Speaking of making real improvements in people’s lives, this new piece by Tony Romm on the failings of the government’s Lifeline program offers a comprehensive take on how we could make dramatic improvements in access to broadband for poor and rural users of the internet.

-A new report from NYU shows that social media platforms aren’t censoring conservatives or favoring liberals. For example, in terms of video views, partisan left videos on YouTube got 19 billion views in 2020 compared to 16 billion for partisan right videos. Facebook interactions were dominated by President Trump, with 654 million likes, shares or comments compared to 33 million for Senator Bernie Sanders and 22 million for Senator Elizabeth Warren. Same with Facebook interactions with Fox News and Breitbart compared to CNN, ABC News, BBC News, NBC News and NPR. The allegation that the platforms are biased against conservatives is “a mass-aggrievement narrative, deployed as a cudgel by politicians who use it cynically to rally their base,” Renee Diresta of Stanford says.

-Issie Lapowsky reports for Protocol on Chicago’s new partnership with health care scheduling company Zocdoc to streamline the vaccination process. Let’s hope things go better there than they did in Philadelphia, where the city’s decision to partner with an untested startup led by a 22-year-old whiz kid has erupted in scandal.

-Neighborhood forum colonization platform NextDoor has quietly decided to stop recommending political groups to its users, Will Oremus reports for Medium’s One Zero.

Howard Rheingold was quoted in the NYTimes recently (https://www.nytimes.com/2021/02/04/opinion/michael-goldhaber-internet.html):

“Attention is a limited resource, so pay attention to where you pay attention.”

That makes me believe we need less a "reality czar" and more of a online "reality" toolkit. Howard has a good one in his book Net Smart. My notes are available at

http://hubeventsnotes.blogspot.com/2015/11/net-smart-how-to-thrive-online.html

Fox "News" and it's evil spawn Newsmax & Onan along with huge funding of right wing groups by Koch Brothers with a large dash of Russian disinformation attacks are IMHO active root causes that need to be addressed along with all your other great points.