A Tale of Two Whistleblowers: Daniel Ellsberg, Frances Haugen and the Fight for the Truth

Their examples show how small groups of people can change the world, but at too many institutions, secrecy and fear still prevent good people from coming forward.

By coincidence, I finished reading Frances Haugen’s excellent new book, The Power of One: How I Found the Strength to Tell the Truth and Why I Blew the Whistle on Facebook, this past Saturday, the day after the man who leaked the Pentagon Papers, Daniel Ellsberg, died at the ripe old age of 92. This confluence of events has gotten me thinking about a mix of complex questions: when and how individuals may take outsized roles in sparking social change, whether people like Ellsberg and Haugen were the almost inevitable product of the harmful and hypocritical institutions they worked for, and finally, what whistleblowing does (and maybe doesn’t) accomplish.

Back in 2010, I managed to convince Ellsberg to speak at Personal Democracy Forum by suggesting that he meet WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange for their first public encounter on our stage. In the wake of WikiLeaks’ disclosure of video evidence of American war crimes in Iraq, Ellsberg had remarked that had the Internet existed in 1969, he would have posted the Pentagon Papers online. This was an obvious hook to pull him toward the PdF audience. But what convinced him to rearrange his schedule so he could attend was something more personal: in my invitation to him I had mentioned a mutual friend, Randy Kehler.

I had gotten to know Randy first in the early 1980s, when I wrote some pieces for The Nation about the nuclear freeze movement that he had helped found. In the mid-late 1990s, I worked with Randy at Public Campaign on public financing of elections, a reform that was a direct outgrowth of his efforts to dismantle the military-industrial complex. It was there that he told me about a speech he had given at a conference of the War Resisters League in the summer of 1969 about preparing to join his brothers in jail for resisting the draft. Ellsberg, who was still working for the government at the time, had already moved from hawkish support of the Vietnam War to strident opposition, was in the audience.

Hearing Randy speak movingly about the personal sacrifice he was about to make literally changed the course of Ellsberg’s life. As he describes in his memoir Secrets, immediately afterwards he had an emotional breakdown, driven by his sense that “we are eating our young,” and spent an hour on the floor of a bathroom crying. “It was though an axe had split my head, and my heart broke open,” he wrote. “But what really happened was that my life was split in two.” From that point forward, Ellsberg decided that he was willing to risk prison and give up his career as a defense analyst for the RAND Corporation, and forfeit all his social relationships, in order to do everything he could to end the war. Copying and then leaking the Pentagon Papers came next.

As I wrote to Ellsberg, “That story has always reminded me how you never know how one person's action can change the world.” And no question his love for Randy (who has a major role in the Ellsberg biopic The Most Dangerous Man in America) along with his admiration for Assange, led him to come to PdF. Unluckily for us and our audience, at the last minute Assange decided not to fly to America. His excuse was that he had been warned by his lawyers to avoid countries that “don’t follow the rule of law,” but in retrospect, it seems likely that by then he knew Chelsea Manning had been arrested and feared he would be next. So we had to conduct the conversation by Skype, which was suboptimal at best and started off with a comical interchange about whether Assange, who hovered on a giant screen behind us on stage, was even wearing pants.

A few weeks before that ill-fated encounter, while we were corresponding about plans for the event, Ellsberg mentioned that he was on his way to Vienna for a conference. Crazily enough, I was already in Vienna, midway through a trip speaking at an e-democracy event and a meeting of European political consultants. And so fate gave me an afternoon and dinner one-on-one with one of my heroes. We met outside his hotel and decided to stroll the wide pedestrian boulevards of downtown, getting to know each other as we walked. But then Dan had an idea—we should go to the Freud Museum, so he could pay tribute to the famous psychoanalyst for having helped remove Richard Nixon from office. Say that again? Dan explained: After he leaked the Pentagon Papers, Nixon and his henchmen in the White House created the “plumbers” unit to plug future leaks, and one of the tasks they were assigned was to break into the locked files of Ellsberg’s psychiatrist, in order to find and spread dirt about him. As it happened, Ellsberg’s shrink was a Freudian. The revelation of the break-in not only derailed the government’s case against him for leaking the papers (he had been charged with espionage, but the judge declared a mistrial), but it also became one of the strongest counts against Nixon in the articles of impeachment that led to his resignation.

What I remember most about our conversation that day (other than a mind-blowing coincidence that is only worth a footnote below) is how much Dan hoped more people in positions of knowledge and power would step forward and tell the truth about what their leaders and institutions were actually doing. “Courage is contagious,” he often said. Indeed, in the stories of whistleblowers there often are direct examples of courage inspiring action. In her book, Frances Haugen, who came two generations after Ellsberg, describes reading about two young women in New York City, Mary Sharmat and Janice Smith, who in 1959 had each on their own decided that they would not participate in an annual compulsory civil defense drill, since they believed there was no way to survive a nuclear attack. Once they found each other, they organized more and more women, eventually gaining real media attention and ultimately helping lead to the abandonment of the drills. Haugen made a study of these women and their subsequent involvement in the movement against nuclear weapons testing her capstone research project at college. Learning about them “became part of who I was to become.” And so stories of courageous dissent do inspire others, though often we don’t know the exact chain of connection. (Haugen also mentions colliding with a young Aaron Swartz when she was helping build Google Books and he was scraping its output for the Internet Archive’s Open Library, but she doesn’t say much about how that interaction might have influenced her other than noting his “punk-rock vibe” of “we’ll just take the data if they won’t give it to us.”)

But while we may lionize people like Ellsberg and Haugen, they are the exceptions to the rule. Tens of thousands of people with high security clearances have worked in the military establishment, but only a handful have gone public with their concerns about war crimes, dishonesty or waste. Haugen writes eloquently and in great detail about the process that led her make her break with Facebook, but while her aim is to inspire others, she also illustrates how hard it is for anyone who has made a commitment to a job and started to garner its benefits to choose to give that all up for a cause.

One of the most poignant stories she shares in The Power of One is what happened in the fall of 2019 after CEO Mark Zuckerberg made the unilateral decision to protect the speech of all politicians from any kind of content moderation. As Haugen writes, more than thirty key decision-makers across the company had worked diligently for months to develop a policy for when dangerous political speech, the kind that risked triggering communal violence, should be taken down. Muslims in India were being described as rodents by top officials of the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party, and this was clearly leading to violence. But before the policy could be embraced, questions arose about what the company would do when Donald Trump inevitably demeaned ethnic minorities in similar ways. In that context, Zuckerberg’s fiat hit Facebook’s Civic Integrity team, where Haugen worked, like a thunderbolt.

As Haugen writes, Samidh Chakrabarti, the head of Civic Integrity, called an emergency all-hands meeting to clear the air:

“He began by telling the story of his own journey on Civic Integrity. At one point he flashed up MRI images of his spine to illustrate how much he, just like the rest of us, had sacrificed to pursue the mission of Civic Integrity: He had spent so much time sitting and working in the wake of 2016 that he had ruptured at least one if not two discs in his spine. He talked about missing time with his children during those priceless years when they were small, and how sometimes the cost felt like it was just too much to bear. This went on for at least twenty minutes. I can’t speak for the room, but I certainly thought the only way this monologue could end was with Samidh stepping down. Stepping down would not have been a rash act, either—Civic Integrity had worked according to the Facebook process. The group had diligently wrangled vastly competing internal and external interests into a brokered compromise. It showed remarkable disrespect [on Zuckerberg’s part] to think you could spend a weekend alone on your computer and do it better. And then Samidh swerved and said that all of that didn’t matter, though, because we were working on something so important the sacrifice was worth it, and he was going to continue to fight on.”

Haugen writes a lot about the dilemma of the committed insider. “Now that you were at Facebook, inside the curtain that shielded the public from the truth, you knew exactly how bad things were on the platform and Facebook’s role in it. But you also knew that the work to blunt those damages was underfunded and lacked institutional will. If you stayed, you knew there was at least one more person trying to keep the train from jumping the tracks….If you left, you knew there was one person fewer trying to buy enough time for the better angels of men to prevail. A large part of what would push me over the edge into whistleblowing was that I watched that formula play out tragically over and over again.” For her the final straw was when, right after the 2020 election was over, the company decided to disband its Civic Integrity team.

As it happens, I know and like Samidh Chakrabarti, as he was a frequent attendee of Personal Democracy Forum starting before he was at Facebook, when he was part of Google’s Civic Innovation team. At both places he helped build relationships with civil society organizations, which included providing sponsorship support for events like ours. And so we had a bit of a delicate dance: Big Tech platforms wanted to be able to tell their story at places like PdF, and we were willing to take their money only as long as we could also showcase their toughest critics. Samidh was also a regular attendee (and sponsor) of mySociety’s annual conference on global civic tech (TICTeC). My notes from a presentation he gave at the 2019 TICTeC conference show that Samidh truly thought his arm at Facebook was making a meaningful difference—blocking hundreds of millions of fake accounts every day, sleuthing out clusters of coordinated actors using multiple groups and accounts for inauthentic behavior, accelerating the taking down of information operations, creating more transparency for political ads, working with third-party factcheckers to reduce the spread of demonstrably false information, removing thousands of examples of voter suppression content, and getting better at stopping pop-up foreign spammers trying to influence elections. He was also proud of civic features his team added to the Facebook user experience, like badges so politicians would know when someone commenting was a constituent, peer-to-peer voter registration drives, and day-of election reminders.

But what Haugen shows, quite convincingly in my opinion, is that none of this was anywhere close to enough. Facebook was wreaking deadly havoc across the world, doing the most damage and taking the weakest corrective steps in the places that were most vulnerable and least powerful. In the United States, where it made the most money per user and where it had the greatest vulnerabilities to political and social pressure, it made some investments in reining in disinformation and responding to hate speech. But even these, Haugen shows, were putting lipstick on a pig. It mattered more to top executives that Facebook defend against negative press than actually solve the problems causing the bad headlines. (Hence the partnerships it made with third-party factcheckers that, at best, only touched the surface of the billions of pieces of content shared by the platform’s users.) And in much of the world, which Zuckerberg megalomaniacally sought to “dominate,” Facebook colonized the online space so effectively that whole populations didn’t know there was an internet beyond its familiar blue borders, while spending almost nothing to protect people in those countries from the hyper-polarization its souped-up recommendation algorithms rewarded. By contrast, Haugen notes, big Facebook advertisers – anyone spending say, $100,000 monthly -- automatically got special treatment.

Even worse, because the entire internal organizational structure at Facebook was built around metrics, anyone who sought to prevent bad things from happening was at an incredible institutional disadvantage. If you couldn’t find a way to measure a problem, you couldn’t work on it. How could you demonstrate your value if the thing you worked to prevent didn’t happen, so the success couldn’t be tallied? And the problems of disinformation and hate speech also tended to produce solutions that only cost the company money. If you upgraded a reporting system that so-called “trusted partners” had been given in order to alert the company to fast-breaking local issues, then you just caused more reports to be filed that needed attention. This was not the kind of thing that employees facing quarterly performance reviews got positive ratings for. Nor did the Growth team at Facebook, one of the power centers at the company, take kindly to any changes to its sharing algorithms that might reduce usage—even if that meant leaving abusive or dangerous behavior untouched.

As I’ve written before, Facebook is like an extremely badly designed network of nuclear reactors. Connecting people to each other, like putting uranium-laced fuel rods close to each other, produces a lot of energetic interactions that can be converted into a valuable resource. In the case of Facebook, that resource is our attention, which it sells to advertisers. All the external polluting effects of Facebookization have been dumped on the rest of society. The cloud that Zuckerberg has cast over the world isn’t anywhere as visible as the cloud that spread from Chernobyl, which is why he’s been able to commit social ecocide for so long. The question remains, why do any of us still allow this to go on?

And that’s the ultimate dilemma of the whistleblower. What if, as Henry David Thoreau wrote, you “Cast your whole vote, not a piece of paper merely, but your whole influence,” and then the beast you are fighting doesn’t die? As Haugen notes, Facebook’s stock price peaked at $378 a share the week before the first Wall Street Journal story sourced to the files she liberated appeared. It slid downhill all the way to $90 at the beginning of November 2022, a more than 75% decline. But now it’s up to $280, a healthy rebound. The company spent a whopping $280 million standing up the so-called Facebook Oversight Board, a semi-independent group that sounds like it has real power to oversee the company but, as Haugen rightfully notes, can only make decisions about whether individual pieces of content were appropriately moderated, and a whole cottage industry of scholars and journalists (I’m looking at you, Kate Klonick) fell for the bait and obsessed about that board, referring to it as Facebook’s equivalent of the US Supreme Court. I suppose the analogy has some truth but only in the sense that like our Supreme Court, Facebook’s oversight board serves the interests of its owner, not the general public.

At least in Europe, Haugen’s revelations have contributed to meaningful change, starting with the passage of the Digital Services Act, which will force some transparency onto all the major tech platforms starting in 2024. Other than that, the only good news about the company formally known as Facebook is the steady decline in its user base, as younger people gravitate toward platforms like TikTok instead. Haugen has launched her own nonprofit, Beyond the Screen, using it to continue to fight online harms (though so far it itself has no online footprint), while her former colleague Samidh Chakrabarti has used his time after leaving Facebook to immerse himself in the risks that may be generated by AI, and to join the advisory board of the fledgling Integrity Institute.

As for Meta/Facebook, like a zombie that has taken shots to the head, it just keeps on going. And that’s because our democratic systems for public oversight are still no match for Big Tech. Haugen writes about briefing top congressional staffers from the Senate Commerce Committee that took her blockbuster testimony and asking whether there were other tech-focused staffers she should be giving documents to. The people she was meeting with looked at each other and then responded, “I know that sounds reasonable and I would say yes [the staffer paused, conveying how little he wanted to finish his sentence] if we could go two weeks without another committee staffer leaving for a job at a Big Tech firm.” And so it goes.

About That Footnote

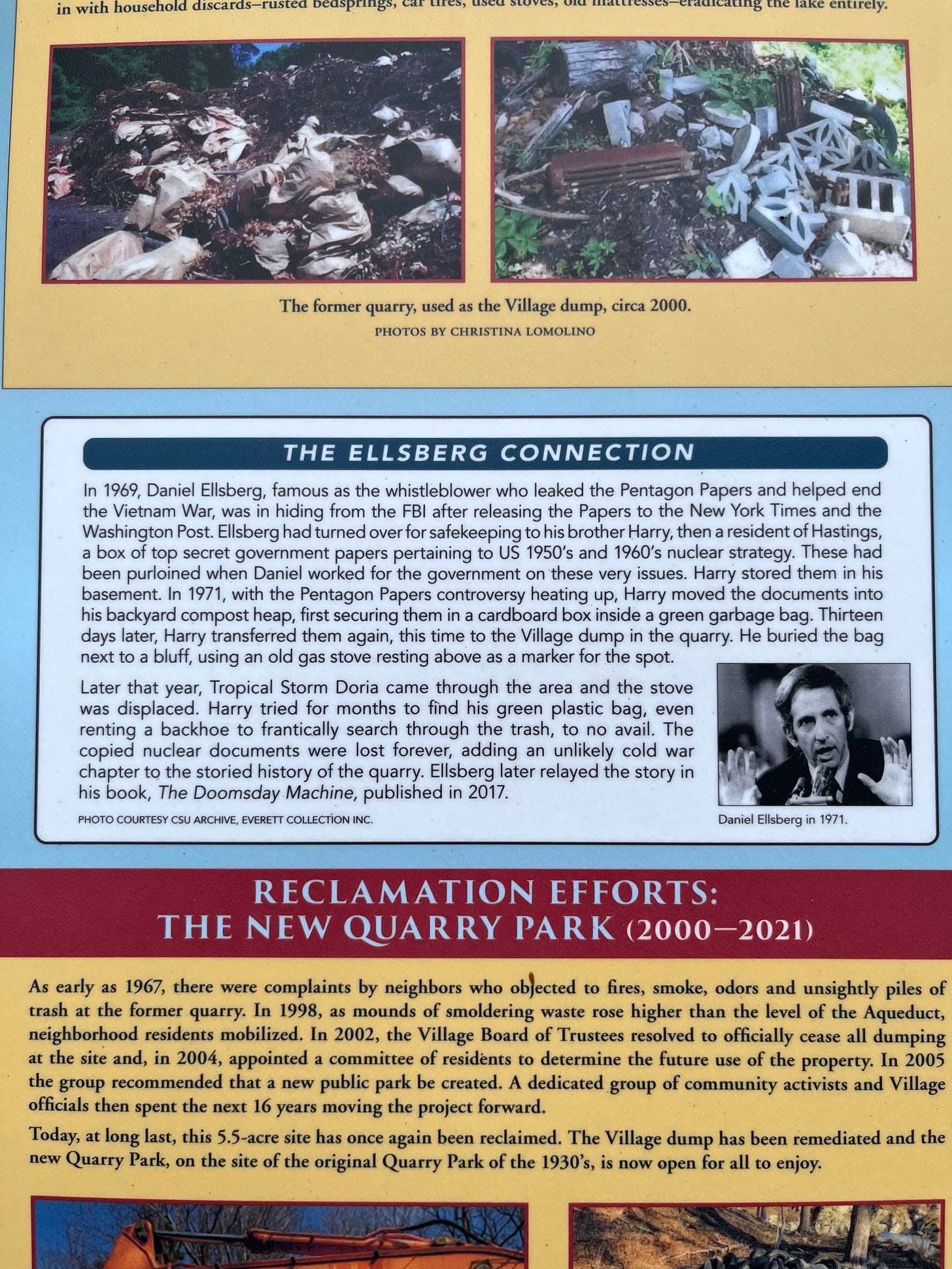

At the end of our afternoon jaunt through Vienna, Ellsberg and I found a restaurant for dinner. He asked me where I lived, and I said Hastings-on-Hudson, just north of New York City. “Hastings! I know Hastings,” he exclaimed. He then proceeded to tell me the astounding story of how, in addition to the Pentagon Papers, he had also copied a box-load of documents related to US nuclear war fighting plans and then given them to his brother Harry, who lived in Hastings, for safekeeping while he focused on Vietnam history first. My jaw kept dropping as I listened. In 1971, when The New York Times and the Washington Post started publishing their stories on the Pentagon Papers, Harry moved the box from his basement to hide it under a compost heap in his backyard. Fearing the FBI was on to him, he moved it to the town trash dump, the site of an old quarry. Then disaster struck when tropical storm Doria hit the town and, despite weeks of searching, the box was lost. As I listened, all I could wonder was what kind of cosmic sense of humor decided to connect us?

Odds and Ends

On my reading list:

--“Analysis of the Changing U.S. News Media Landscape and Strategies Toward Delivering Civic Value,” by Sophie Elliott, Arkadi Gerney, Tim Hogan, Sarah Knight, and Akhil Rajan.

--"Overview and Key Findings of the 2023 Digital News Report,” by Nic Neuman of the Reuters Institute.

--"The Antidote to Authoritarianism: How an Organizing Revival Can Build a Multiracial Pluralistic Democracy and an Inclusive Economy,” by Beth Jacob and James Mumm of the People’s Action Institute.

End Times

This, I promise, is my new favorite government website. I checked the link. Three times!

Worth noting is the difference in how Ellsberg was treated then (facing jail, saved by the Supreme court, after that lauded by the media) and how Assange is being treated now (facing jail, either ignored or criticized by the media). Ellsberg admitted he had been secretly given a backup copy of the leaked Afghan & Iraq war logs, in case WikiLeaks was prevented from making them public. He pointed out that his possession of the docs made him equally culpable with Assange and demanded that he be indicted too.