As war rages, where is the US peace movement?

We don’t have an antiwar movement in America; what we have is two pro-conflict movements: one that insists Israel must win and one that insists Palestine must win.

Monday morning, as I pondered what I would write about this week, I got a call from my friend Janice Fine, a longtime organizer with deep experience across many movement projects who now teaches labor studies at Rutgers University. What happened to the antiwar movement, she asked me. “The current binary—where you can only be either pro-Israel or pro-Palestine—is making it really tough for many movement people to find their place,” she said. “We need to create a place for people to stand in the breach.”

She got me thinking. What kind of movement(s) have been galvanized in America since Hamas’s October 7 attack on Israel? Who is showing up in the streets and what are they saying? Why is the debate so polarized that many people of good will are staying on the sidelines? And what is the polarization doing to public opinion—is it changing anything?

Let’s start with the data. According to the Crowd Counting Consortium (CCC), an academic network that has been collecting and parsing news reports about political protest activity in the United States starting in January 2017, since October 7 there have been more than two thousand solidarity rallies, vigils, and marches focused on supporting either Palestine or Israel. Jay Ulfelder, a Harvard-based researcher who helps run the consortium, compared the scale of activity to the May-June 2022 surge in abortion rights protests surrounding the Supreme Court’s Dobbs decision. He also said it was less intense than the post-George Floyd uprising on 2020, when CCC logged more than 400 events per day.

Still, it’s been a lot. In the first ten days after October 7, pro-Israel events outnumbered pro-Palestine events, with CCC tallying about 270 of the former and 200 of the latter. Since then, pro-Palestine protests have surged, with about 130 taking place in the three-day period of October 20-22 and roughly another 500 in the two weeks following. Ulfelder suggests that Israel’s decision to cut off water and electricity to Gaza and to order Palestinians to move south kicked the protests into a higher gear.

With the exception of the “March for Israel” rally in Washington, DC on November 14, which drew a huge crowd—similar to a pro-Palestine march there ten days earlier—the size and volume of pro-Israel rallies has not matched what was seen in the first weeks after Hamas’s attack. Overall, through Sunday November 26, Ulfelder tells me that the consortium has recorded 1,868 pro-Palestine rallies, demonstrations, marches, vigils, and direct actions in 468 different cities and towns across 49 U.S. states, DC, Puerto Rico, and Guam. “We have information about crowd size for about 57% of those events (1,058), and we roughly and conservatively estimate the total crowd size for that 57% at 677,000 people, with a median crowd size of 125.” He says they’ve noted the presence of counter-protesters at nearly 200 of those events, or about 11% of the time, and the presence of supportive elected officials at just 20 of those events, or about 1%.

On the other side, CCC has recorded 430 pro-Israel rallies, demonstrations, marches, and vigils in 259 different cities and towns across 45 U.S. states and DC. Ulfelder says, “We have information about crowd size for about 70% of those events (302), and we roughly and conservatively estimate the total crowd size for that 70% at about 291,000 people, with a median crowd size of 200.” Counter-protestors have been more sparse, showing up at just 31 (7%) of those events, while elected officials from governor on down have appeared at 101 (24%) of them.

What are people saying with these rallies?

On the pro-Israel side, the imagery has been dominated by the Israeli flag, or a blended Israeli/American flag, along with signs attacking Hamas, referencing the Holocaust and displaying the faces and names of the people taken hostage into Gaza. These, it seems, have remained constant, while the chants and signage prominent at pro-Palestine events has shifted, according to an Los Angeles Times analysis done with consortium data.

At first, words like “apartheid” and “resistance” were dominant, but more recently that has changed. The incendiary phrase “resistance is justified if Palestine is occupied” (or variations of it) was used in at least 88% of the pro-Palestine events through October 15; a month later that had dropped to under 10% of such events. Likewise, the phrase “from the river to the sea, Palestine will be free” was seen or heard at more than 40% of such rallies in early October; a month later it was found in less than 17%. “Cease-fire” was only prominent in 8% of pro-Palestine events in the second week of the war; since week four it has been heard at more than two-thirds. And as this chart below from the CCC shows, it wasn’t until the second week of the war that pro-Palestine protestors really started charging Israel with “genocide”; through the middle of November roughly half of those events have highlighted that claim.

What’s missing from this picture? Events that bridge rather than exacerbate the conflict by expressing sympathy with all civilian casualties, Israeli and Palestinian alike, and/or that call broadly for de-escalation and compromise that would ensure peace and security for both peoples. Talking to journalist Marc Lynch last month, Jeremy Pressman of the University of Connecticut, another founder of the CCC, mentioned seeing only a very small number of such gatherings, citing a vigil in Brighton, New York, at the Islamic Center of Rochester or the “Interfaith Peace Vigil for the Middle East” at Mt. Sinai Congregation in Cheyenne, Wyoming.

I asked Pressman yesterday why he thought that was the case. He said it was hard to speculate about non-events, but suggested that it could be because America is already so polarized people don’t feel comfortable speaking out with simultaneous empathy, or because news coverage of the conflict has inevitably focused more attention on Israel’s attacks than Hamas’s. But he also suggested that all the organizations with significant backing were on one side or the other; “without an organization pushing the bridge idea, it doesn’t get off the ground.” (Here’s an example of a promising effort in Washington, DC led by a new ad-hoc group calling itself Am Shalom: Jews and Allies for Ending Violence, which has started holding vigils near the White House and has one scheduled for Sunday December 3.)

So, to sum up, if you aren’t fully on board with backing Israel but also aren’t sure if you’re comfortable standing up alongside people who may have celebrated Hamas’s October 7 attack as “resistance” and who throw the word “genocide” at Israel or President Biden (as in “Genocide Joe”), but want to urge both sides to de-escalate and compromise, it’s understandable if you aren’t in the streets. Right now, visible public participation in the debate over the Gaza war is highly polarized. As my friend Janice Fine suggested to me, we don’t have a peace or antiwar movement in America; what we have is two pro-conflict movements: one that insists Israel must win and one that insists Palestine must win.

How have we gotten so polarized?

I have a couple of answers. First, there’s the natural human tendency to form in-groups that cohere more strongly by identifying an out-group they are against. And we’re more likely to justify immoral or dishonest behavior if it benefits our in-group.

Second, social media algorithms definitely intensify this tendency. Posts about political opponents are substantially more likely to be shared of Facebook and Twitter/X than posts about one’s own group. Back in 2018 a Facebook research team warned that its algorithms “exploit the human brain’s attraction to divisiveness” but according to the Wall Street Journal, that team was shut down and the company declined to implement recommendations that would have made the platform less divisive. So we can blame a nice Jewish boy from Dobbs Ferry, NY and his willingness to “move fast and break things” for some of the problem.

Third, since the “racial reckoning” summer of 2020, when many organizations, including numerous corporations, made public statements about their commitment to racial equity, the expectation has grown that all kinds of previously passive or neutral entities will respond positively when activists demand that they “take a stand.” It’s not clear how useful this expectation has proven to be—for a few years it led to a boom in the “diversity, equity and inclusion” consulting world, though many commitments made by corporate America during that heady summer have since evaporated. And we’ve been living with an energized white backlash ever since then. Is it a good thing that today many organizations with no specialization in the Israel/Palestine conflict have felt compelled to take a stand, even if that has damaged their ability to function? (If you think such statements have petered out, they have not—check out this new one from more than 200 immigrant rights groups and leaders.)

Fourth, it can’t be denied that as Israel has moved to the right since the second intifada, largely under the leadership of Benjamin Netanyahu, young people in America—Jews and non-Jews alike—have grown significantly less supportive of it, more sympathetic to Palestinians, and more open to the anti-Zionist, decolonization framework. Even though Jewish Voice for Peace was founded decades ago, its forthright anti-Zionism is attractive to younger people yearning for clarity in a world that keeps telling them they have to compromise on their values and hopes.

Fifth, and perhaps most pertinent here, some activist organizations subscribe to a theory of change that involves deliberately choosing to polarize the public around a controversial issue. The legendary Saul Alinsky taught this approach in his “Rules for Radicals,” telling organizers to “pick the target, freeze it, personalize it, and polarize it” in order to heighten attention around the target. Momentum, an organizing network that was inspired initially by the work of Mark Engler and Paul Engler, teaches a similar model. It urges groups to “frontload” their organizational design in anticipation of “moments of the whirlwind” when a moral shock generates mass protest and then to adopt a morally distinct stand along with disruptive and confrontational tactics that may both weaken their opponent and draw supporters toward them for absorption.

As the Englers wrote in their book, This is an Uprising, in such moments with such a strategy, large segments of the public may move from indifference to engagement, and generating active antagonism isn’t necessarily a bad thing. “For polarization to pay off,” they write, “the positive must outweigh the negative. And here the reaction of the general public—those not already aligned with either side—is critical. Acts of sacrifice and political jui-jitsu can help to foster an empathetic reaction: they convince the undecided to side with communities in resistance rather than forces of repression. When the process works, members of the public are alienated by the extremism of reactionary opponents, and they acknowledge that something needs to be done to address the movement’s grievances.”

This certainly describes what groups like IfNotNow (a group incubated by Momentum) and Jewish Voice for Peace have been doing since October 7, not only in their rhetorical decisions to invoke the Holocaust and accuse Israel of “genocide” in Gaza, but in their disciplined use of street disruptions like the takeover of NYC’s Grand Central Station on October 27. One could argue that polarizing the debate by deliberating framing Israel as an “apartheid” or “settler colonial” state can give previously indifferent or less engaged observers an easy way into understanding the conflict and picking a side.

As one veteran progressive organizer familiar with the Momentum training model said to me this weekend, “It’s not just like there is a moment of the whirlwind and you just sort of sit around in the town square and wait for people to come to you. You call a big shot. And then people gravitate towards that because it’s so morally clear.” Whether or not what Israel was already doing to Gaza in the days after October 7 amounted to genocide didn’t matter; one article in the radical Jewish Currents magazine called it ”A Textbook Case of Genocide” on Oct 13 was enough. “Part of the challenge here,” this person told me, “is that most people in this country, not even Jews, have a position on Israel/Palestine. It’s like number 12 on the list of things Jews care about in this country on any given day. So what Jewish Voice for Peace and IfNotNow did was more pull people off the sidelines less than convince the big middle to agree with them.”

There’s much to be said for the polarization model of social change organizing, but it doesn’t always work. As the Englers write, “Polarization can also go bad. For movements to benefit from a state of heightened conflict, its participants must make sure of two things: first, that they are drawing in more active supporters than opponents, and, second, that even if their methods are perceived as extreme or impatient, the tide of public opinion is pushing toward greater acceptance of their views. This requires strategic judgment.”

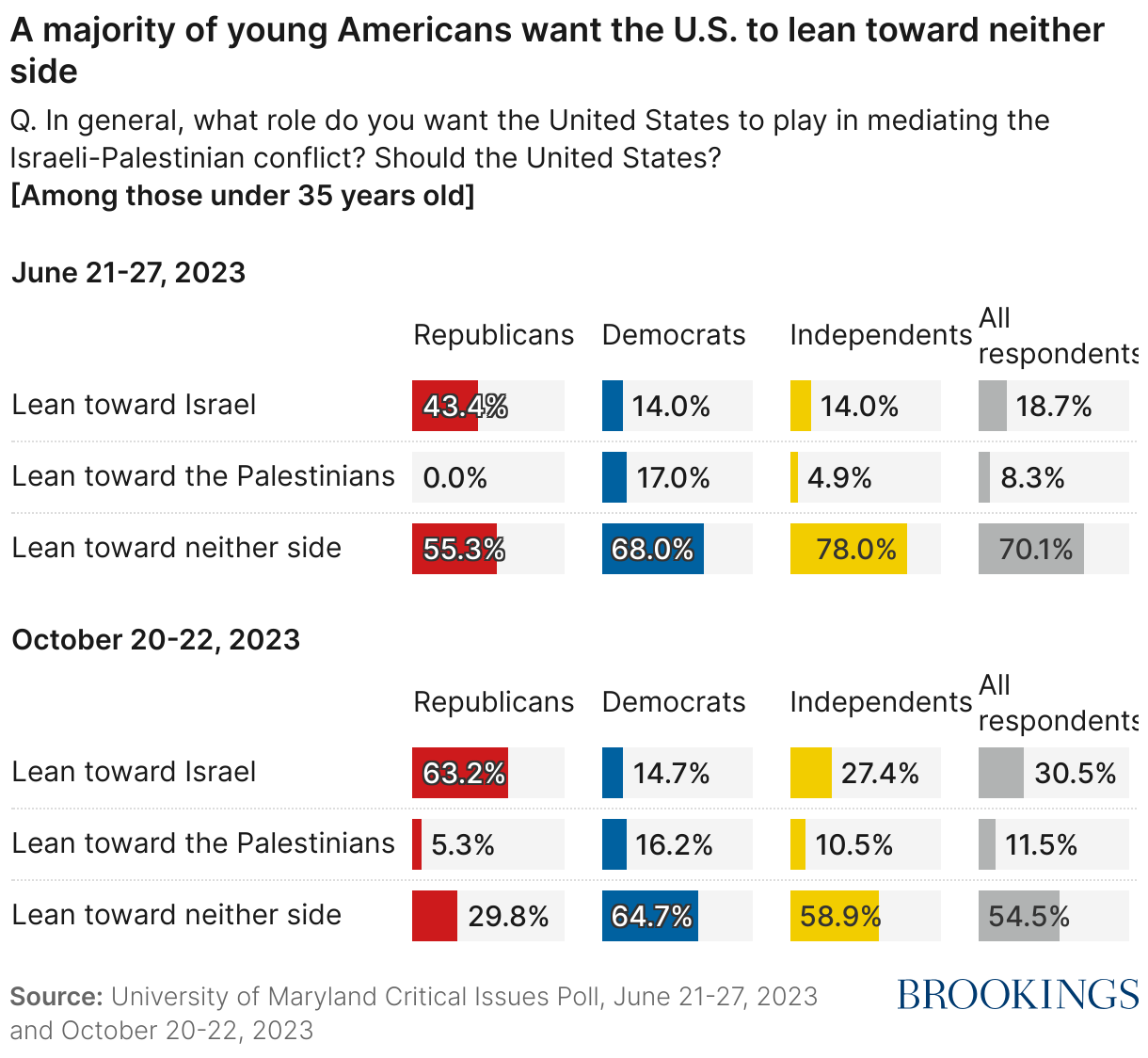

Polling on public attitudes towards the Israel/Palestine conflict since the war began suggest a mixed picture at best for the polarization strategy. Americans have somewhat more positive feelings toward the Palestinians than in the past, but according to YouGov, support for the idea that they should have their own state has dropped to 47% (in a late October poll) compared to 68% back in 2009. A different survey conducted at the same time, fielded by Ipsos on behalf of the University of Maryland, found that Republicans, independents and Democrats alike had become more pro-Israel. Asked “what role do you want the United States to play in mediating the Israeli-Palestinian conflict?” all three groupings said they wanted the US to lean more toward Israel than they did last June, when the same question was asked. Even among Democrats, support for leaning toward the Palestinian side ticked down. People under the age of 35, who have become substantially more sympathetic to Palestinians (as evidenced by this recent Quinnipiac poll), also showed little change in their attitudes about how the US should approach the conflict.

So, despite the flowering of protest activity, especially on the pro-Palestinian side, it’s far from clear that the choice to polarize the debate is actually helping build the political power needed to alter the course of US policy. But it is helping fracture the Democratic Party. Let’s hear it for performative extremism! (“What do we want? Nuance! When do we want it? Now!)

So where is an antiwar movement?

The vast majority of groups that have historically engaged in antiwar or peace activism, many of them faith-based, have issued statements calling for a cease-fire in the fighting. That link will take you to a big spreadsheet maintained by the Fellowship of Reconciliation, which has been advocating and organizing for peace and nonviolence since 1914. But what their spreadsheet doesn’t show is which groups are trying to fill the “breach” and which are choosing one side. MoveOn.org, the biggest progressive umbrella group, which generally leans into issues based in part on what campaigns resonate most with its millions of members online, has pushed for humanitarian aid for Gaza, a stop to bombing civilians and the release of the hostages. That petition has more than 430,000 signatures. Notably, that statement from MoveOn makes no mention of apartheid, colonialism or Zionism and just concludes that “the people of Palestine and Israel deserve to live their lives without fear of violence and mass death.” Maybe MoveOn is onto something?

In the hopes of getting a different take on the political challenge we’re facing, I reached out to Sara Haghdoosti. She’s the executive director of Win Without War, an antiwar organization that was founded about twenty years ago to oppose the invasion of Iraq by a coalition of progressive organizations including the National Council of Churches, Physicians for Social Responsibility, Rainbow/PUSH, Business Leaders for Sensible Priorities, Sojourners, NOW and MoveOn.

I asked Haghdoosti what had happened to the antiwar movement in the last twenty years. If you haven’t noticed, the last big antiwar demonstration in the US took place in 2007, when George W. Bush was still in charge of the war in Iraq. Once Barack Obama took over, mass protests against US-backed wars basically ended and peace organizations took on more of a lobbying role inside the Beltway than a grassroots organizing role. Haghdoosti said, “In many ways the movement for peace and justice is stronger than ever before. More people are critical or at least skeptical of foreign wars than they were twenty years ago. The number of Members of Congress that care deeply about this issue and are pushing on it through sanctions reform, war powers reform, accountability for civilian deaths is also larger. While our demands may not always be met - they’re not laughed out the room the way they would have been two decades ago.”

She noted that Obama won the presidency in part on an anti-Iraq war platform. “During his presidency, the movement took on AIPAC when it came to diplomacy with Iran and won. People may not agree with the policy choice, the fact that Congress also voted against intervention in Syria during that time shows how the strength of the peace and justice movement had bipartisan and strong public support and shaped outcomes. The same movement pushed back against a lot of the Trump administration’s worst instincts - like having military parades in DC, the Muslim Ban, and major organizing after the Suleimani assassination.” She admits that the movement hasn’t been as effective with Biden, but “But the peace movement is often underestimated in terms of its power and in shaping the agenda.”

As for how Win Without War has responded to the Gaza crisis, she said, “The lessons of the endless post 9/11 wars are a key part of our DNA. We also fundamentally are a progressive organization that believes people’s liberation is tied up together. This moment has been a reminder of that principle in a profound way for us because of the work we do and who we are. I’m a Muslim woman, my kids have Jewish and Muslim heritage - I want them to be proud of both family traditions and to never have shame in either one. Stephen Miles, our President, is Jewish. For us, organizationally, we’re not an organization that focuses on only this conflict - we do have the unique benefit of being rooted in many communities in a way that has really helped navigate this moment.”

“Here’s what we’ve done so far, we condemned the October 7 attacks by Hamas. We’ve also strongly condemned the way the Israeli government has used collective punishment in Gaza, the use of starvation as a tactic and the targeting of civilian infrastructure. We’ve been strongly advocating for a ceasefire for a few reasons: the last few days have shown that diplomacy is key to getting hostages to safety. I can’t imagine what those families have been going through and we need to do all we can to bring hostages home.”

“Also, we fundamentally don’t believe the Israeli government's goal of eradicating Hamas through military tactics is possible. Twenty years of war didn’t eradicate the Taliban or Al Qaeda - in fact, those conflicts were used as recruitment tools for those same organizations and spawned even more extreme groups. It’s crucial to also remember this moment didn’t happen in isolation, that this is a horrifying escalation of a broader conflict. If anything, what’s happening now illustrates that the approach in Israel and Palestine has utterly failed at bringing real peace or security to anyone. It’s clear that we need to focus on solutions that allow people in Israel and Palestine to be able to have dignity and live and thrive without the fear of violence.”

“Given that, here are concrete things we’ve done. We’ve covered DC in posters for a ceasefire, we created a memorial on the national mall, that acknowledged the hostages and also everyone who had died in the conflict so far to help humanize this debate, we’ve written about the need for the administration to not conflate support for a ceasefire with support for Hamas, and we’ve been connecting members of Congress and key decision makers with Jewish and Palestinian peace activists from Israel, as well as briefing them on the lessons from the endless wars."

What’s not on that list of actions is grassroots organizing outside the Beltway. So we have a gap. Will organizers figure out how to fill it? Stay tuned.

Give a Little Bit

It’s that day when everyone suggests that you empty your wallet in their direction, so here are a few suggestions of who to donate to:

—American Friends of the Parents Circle, which supports the Families Forum: Palestinian and Israeli Bereaved Families for Peace.

—Standing Together, the Israeli-Palestinian solidarity movement.

—Win Without War, working for a US foreign policy rooted in shared values of justice, equality and security.

A fine wine. Not a found one :(

You are like a find wine. Always good. Richer with age. (Though to me u will always be 35).