How COVID Has Accelerated the Future into the Present

When it comes to tech's role in society, signs suggest that surveillance systems are only getting more baked into how we live, learn and work.

“The best minds of my generation are thinking about how to make people click ads. That sucks.”

--Jeff Hammerbacher, early Facebook engineer

“Historically, pandemics have forced humans to break with the past and imagine their world anew. This one is no different. It is a portal, a gateway between one world and the next. We can choose to walk through it, dragging the carcasses of our prejudice and hatred, our avarice, our data banks and dead ideas, our dead rivers and smoky skies behind us. Or we can walk through lightly, with little luggage, ready to imagine another world. And ready to fight for it.”

--Arundhati Roy

As the worst of the Great Pandemic starts to subside, at least here in the United States, our thoughts turn to the future. And one question that I’m going to keep raising in this newsletter is whether we are simply returning to the broken status quo or seizing the opportunities created by this crisis to do things differently. When we wrote Pathways Through the Portal, our field scan of the potential for emerging technologies to work for the public interest, we were so inspired by Arundhati Roy’s April 2020 essay that we used the quote above as the report’s framing epigram.

But thinking about the role of tech in our lives in the last year, I see a lot of signs that things aren’t changing for the better, they’re either just treading water or changing for the weirder. A lot of our generation’s best minds are still focused on the wrong place.

Let’s start with how we’re working and learning during the pandemic. A new report from Koustubh Bagchi, Christine Bannan and Raj Gambhir for New America’s Open Technology Institute finds an explosion in the use of surveillance tools to monitor the behavior of workers and students. First, to supposedly fight COVID-19, many workplaces and businesses are adopting thermal imaging systems (not just thermometer guns), which not only capture someone’s temperature but can also track their movement and biometrics. They also report that some schools and workplaces are making wearable health monitors mandatory. While these can assist with social distancing and contact tracing (SD&CT), there are valid concerns that the spread of these tools “could normalize public and private surveillance of the body, paving the way for location tracking long after the threat of COVID-19 abates,” the authors note. AiristaFlow, one such vendor, is suggesting its customers build on their “investment” in SD&CT tech to log employee activity or ensure that people stay within predefined boundaries, for example.

Second, and arguably far more disturbing, the pandemic is accelerating the use of surveillance tech not just in the workplace but also in educational settings from K-12 to higher ed. The shift to remote learning has fostered a boom in proctoring software. The names of the vendors are an offense to would-be satire writers, because you can’t write satire when reality gives you Proctorio, ProctorU, Honorlock, Examity, and Respondus. As Bagchi, Bannan and Gambhir note, “The proctoring software many universities use relies on a combination of facial recognition and eye-movement tracking that poses privacy and equity threats.” For example, while Amazon has announced a one-year moratorium on the use of its Rekognition facial recognition tool by police, it has not stopped its use in education. Not only do these tools misidentify Black faces at higher rates than white ones, they also erroneously flag neuro-atypical and disabled students at higher rates. They point out that there are dozens of petitions on Change.org from students calling on their university to stop using these tools.

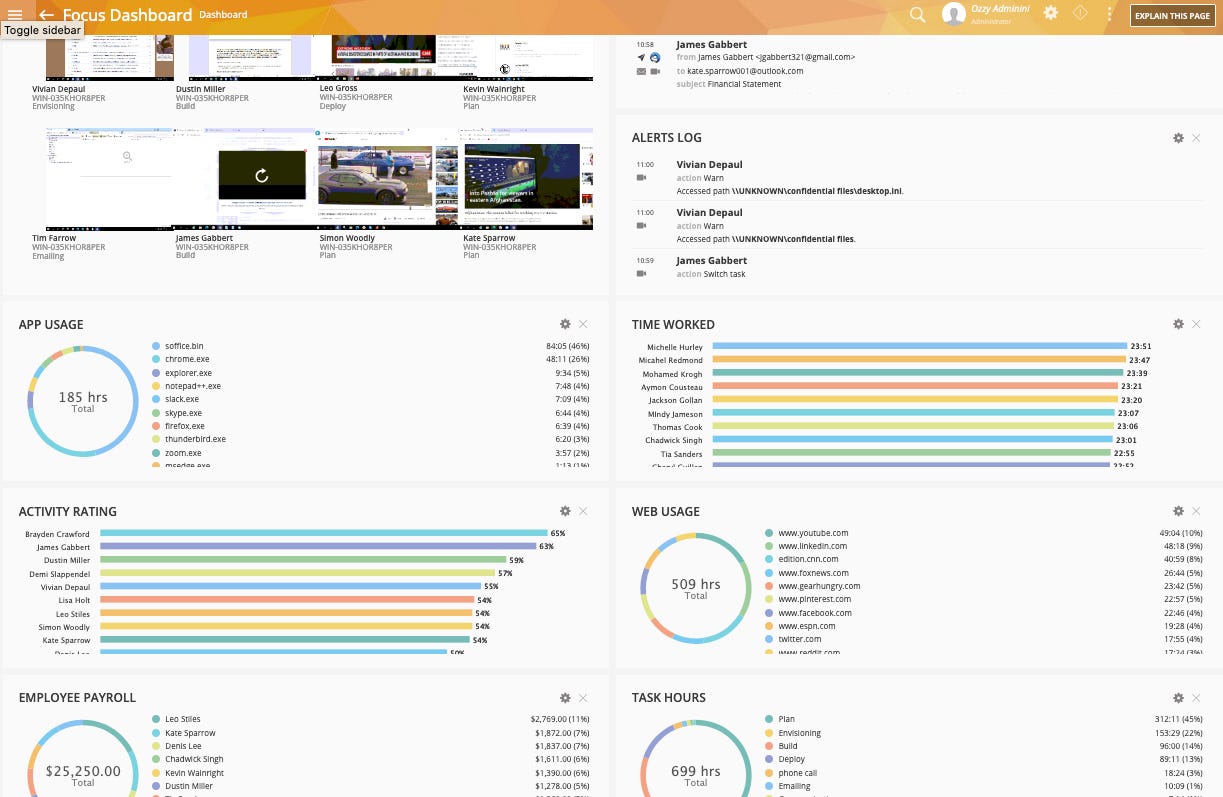

Demand for tools that enable bosses to remotely monitor their employees’ activities is also way up. Again, satire is the loser here. Vendors include StaffCop, Teramind, Hubstaff, CleverControl and Time Doctor. StaffCop offers a live view of remote desktops, automatic screenshotting of employees’ desktops, special monitoring if the boss wants to know when the employer is on Facebook vs Excel, webcam snapshots, and the list goes on. Teramind offers a truly gorgeous dashboard view (see below) that shows a live montage of employee screen activity, along with nifty bar graphs showing how much time they’ve worked, their app usage, an activity rating and a sweet little tool for comparing how much each employee is costing you in payroll.

Naturally, these companies are telling reporters that cheating by remote students and employees has gone way up since the pandemic started, and this is probably true. But using flawed and intrusive tools in the midst of an emergency to try to bend people back towards “normal” is a terrible solution. But at least one-quarter of US companies have put new tracking software on the laptops of their remote employees since last year. “We were already moving in this direction of passively monitoring our employees, listening to them and watching them, and asking them less and less,” Brian Kropp of Gartner told Computerworld last fall. “What the pandemic has done is just accelerate the speed at which that is happening... They were going to get there eventually; the pandemic has just accelerated the future into the present.”

These Aren’t Faster Horses

Five years ago, after Edward Snowden’s revelations and the Cambridge Analytica-Facebook scandal, sci-fi writer and privacy activist Cory Doctorow saw a silver lining, arguing that “We are past peak indifference to online surveillance: that means that there will never be a moment after today in which fewer people are alarmed by the costs of surveillance.” At the time, I thought he was right, but the irresistible momentum of technologies that offer convenience and efficiency still seems to be outpacing any unmovable objections of people newly awakened to the need to defend their data and their selves from further colonization.

In the last few weeks, this has hit me from several angles.

In late February, our Prius died and we needed a new car. We got a new 2021 Toyota RAV4 Prime, which is a plug-in hybrid. On a fully-charged battery, the car can go somewhere between 40 and 50 miles before the gas engine needs to kick in. I’m thrilled to report that so far we’ve driven about 450 miles on about 4 gallons of gas, which translates to about 112 miles per gallon.

What I’m not thrilled to report is it’s 2021, and I own a sophisticated computer on four wheels that is also a surveillance machine. According to Toyota’s ill-named “Privacy Notice,” their fleet of cars come with “Connected Services” that collect my personal information, vehicle location data, current vehicle information including its fuel economy, how we drive it including the use of steering and braking functions, engine performance data, information on how we interact with its multimedia screen, and voice recordings, some of which Toyota says it may store for up to 20 years. While the company says it will protect this data, it also informs us that it will share it with various third parties and that it can’t really promise it won’t have a data breach.

Now, I’m an outlier and I actually take the time to read the terms of service and “privacy” notices on products and apps, but an unwitting buyer or leaser of a Toyota equipped with Connected Services is deemed by the company to have “agreed” to these terms when they get the car and don’t deactivate them. In other words, a surveillance machine by default. I called Toyota’s line to find out more and had a confusing conversation with a customer service representative who mainly wanted to sell me on activating its Safety Connect option, which is free for one year and which offers to send emergency assistance if I hit the car’s SOS button. He indicated that based on our car’s VIN number that it didn’t have all the Connected Services, but when I tried to get him to explain how I might personally access that data, he hung up on me.

What I’d really like is a way to view my car’s performance data and share that information with other RAV4 owners. But I’m like the person who understood that faster horses wasn’t what Henry Ford was building. The four-wheeled computers we call cars do come with on-board diagnostics, but while there’s a fair amount of talk about building “data trusts” to enable trustworthy third parties to help people manage and benefit from their own data, no one is doing anything like this, ye. One company that did offer a way for ordinary consumers to access their vehicle’s performance data, Automatic, was shut down by its parent Sirius XM last May due to COVID.

Surveillance still seems to be the default assumption of lots of start-ups. Take Maple, an app with the oh-so-alluring-in-the-age-of-COVID slogan of “Parenting is hard, what if we made it easier?” Their home page is gorgeous. And the idea of beautifully designed app that might help families and other intentional small living units share tasks more seamlessly sounds great. So I requested access and downloaded the app. But after starting the registration process by putting in my name, phone number, birthdate and city, I stopped short. The very next screen of Maple asks me to tell it what responsibilities I take care of for my family in intimate detail, followed by asking for the names of my kids.

So I wrote to Maple support. “Did I miss the step where you first tell me what your Terms of Service are, what data you are collecting and how you are using it? Shouldn't that come before I start telling you whether I have to buy diapers, pump, or make dinner? I realize this is a new service but it seems like you should be clear from the start how my data is being collected and used.” Michael Perry, who it turns out is Maple’s founder and CEO, wrote me back pointing to where those documents live on their website (but not in app). And he added, reassuringly, “With that being said, we do not share or sell any of your or your families data.”

Well, in fact, the company’s privacy page says that it does share my data as part of “Facilitating connections to, and transactions with, third-party partners as part of our Services,” and that “We may share your personal information with business partners to provide you with a product or service you have requested. We may also share your personal information to business partners with whom we jointly offer products or services.” They also admit that if they get bought or go out of business, “your information may be sold” as part of such transactions.

This is standard operating procedure for most start-ups. When I flagged my concerns to Perry, he insisted “We take family privacy and data very seriously, and if you get into the app you will see that we don't share information with any of our partners. You individually have to sign up for those services.” But, he added, “The language is protective (and flexible) to the Company to better align with our long term ambitions/ roadmap- but will still give the privacy power to the user.”

In other words, buyer beware.

Passing peak indifference to surveillance capitalism doesn’t mean that enough consumer demand has shifted to cause companies to value user privacy more seriously, or for the programmers that build these whiz-bang apps to make them more private by default. That’s the lesson a group of students at Amsterdam’s CODAM programming school brought to the annual Mozilla Festival last week. They held a “creepathon” (a lovely portmanteau for a hackathon where you explore a public dataset for its privacy violating properties) and presented their findings on Venmo, a money-transferring app whose data is still publicly scrape-able even after a graduate student showed two years ago how easy it was to downloaded hundreds of thousands of transactions from it. The CODAM students were able to find 300 Venmo transactions by foot fetishists, including several whose personal information was plain as day. In another case they traced a Venmo user from his publicly-shared purchase at a sports bar in San Diego back to his parents’ names and address and his own public criminal records. Asked about their findings, the students said it wasn’t enough to expect individual Venmo users to change their default settings to private; it was up to the company to better protect its users. Venmo, which is now a subsidiary of PayPal, has more than 50 million users in the US. So it goes.

Odds and Ends

-Supporters of the For the People Act (HR 1/S 1) should pay attention to Jessica Huseman’s important report in The Daily Beast on the problems in how the bill draft handles election administration. Huseman, who has covered the voting system beat better than anyone for many years for ProPublica, says that the bill “comes packed with deadlines and requirements election administrators cannot possibly meet without throwing their systems into chaos.”

-Current reading: I just got my copy of Alec MacGillis’ new book Fulfillment: Winning and Losing in One-Click America, which looks at rising American inequality through the lens of Amazon’s rise. Can’t wait to read it. And looking forward to getting my hands on Jillian York’s new book Silicon Values: The Future of Free Speech Under Surveillance Capitalism.

A trully excdlkent if scary read. Really good work and sharp thinking.