How to Build a "Bigger We" - and Go From Isolated Actions to Cultural Change

Parsing the Freedom Together Foundation's critical new report. Plus, Vu Le's new book on nonprofits and philanthropy and lessons from the Defiance in Chicago.

What a frustrating time to be in the Defiance. Just weeks after No Kings II, the largest nonviolent public protests in modern American history, and days after a sweeping rejection of Trump and MAGA at the polls, the so-called opposition party gave in on the government shutdown with nothing to show for the forty-day effort. Jon Stewart kept saying “I can’t f---ing believe it” on The Daily Show last night, but of course we can believe it, because it’s quite clear that the current generation of Democratic leaders doesn’t understand that we’re in the fight of our lives with an authoritarian movement bent on wielding unchecked power. We have to channel our fury wisely.

As I wrote here back in March, in a post titled “The Defiance This Time”:

“We need to drastically lower our expectations about Democratic elected officials leading the opposition to Trump II. With a few important exceptions, most of these people have no concept of organizing. They’ve risen (and held on) to their positions because they are good at two things: raising money and spending it on TV ads. They see citizens who try to do more than give them money and vote as a threat. This is why top Democratic leadership is constantly stiff-arming or trying to control grassroots activists (be they of the left or more moderate). Such people push their representatives to do things that conflict with what their funders want them to do.”

“….If we’re going to successfully defend democracy and the rule of law in America, it will be because civil society rises to do so and then creates the conditions for the opponents of Trump and MAGA to win future elections (which need to happen inside both parties and then in the general elections of 2026 and 2028). Elected Democratic leaders aren’t going to organize this; instead, they talk expectantly about benefiting from it after it happens.

So, while it is tempting to vent at Senate Democrats for their performative and ultimately half-hearted attempt at playing hardball with fascists, that won’t change a thing. The work remains the same. We have to rely on our capacities to organize and learn how to do so with enough scale that we can change the conditions of our time, and that’s what I hope to keep focusing on here at The Connector.

How to Become More Than the Sum of Our Parts?

So, when was the last time you joined with other people to become something together? Not do something together like vote or sign a petition or attend an event. But become something, like an organization with a shared identity and purpose. Devoted fans of sports teams have this experience, as do committed members of faith congregations, people who join a theater troupe or production, devoted alumni of a college, or veterans of a military campaign. Sometimes people who all work on a political campaign have this experience too. You can tell when people are building a common identity together quite easily—they often wear branded clothing, hats or buttons that reinforce that identity.

But as I’ve been writing here since forever, too much of what passes for Democratic or progressive organizing these days is not about helping disparate individuals become something together, but rather simply extracting time or money from those individuals in order to achieve some short-term goal: a fundraising target or a get-out-the-vote metric. Despite the warnings of social scientists like Robert Putnam and Theda Skocpol for the last few decades about how older social structures like civic clubs and unions were being hollowed out, leaving Americans to “bowl alone,” on the center-left there’s been very little investment in trying to change that underlying pattern. (Not as true on the right, where evangelical mega-churches, gun clubs, and youth movements like Turning Point USA fill these gaps.) And then we wonder why so many people feel disconnected from politics, down on democracy, and attracted to tribalism, xenophobic populism and conspiracy-thinking. If you don’t have a political home, it’s easy to be lost.

A new report from the Freedom Together Foundation’s Faith, Bridging and Belonging Program aims to confront this problem head-on. (FTF, which was previously known as the JPB Foundation, has long been a major backer of groups focused on equity and justice, giving away $2.7 billion between 2012 and 2023. Under its new leader Deepak Bhargava, a longtime progressive movement organizer, it recently announced that it will increase its annual grantmaking to ten percent of its endowment for at least the next two years to address the current polycrisis. So if you aren’t already paying attention to its initiatives, now you know why you should.)

Titled “A Bigger We,” FTF’s report argues that today’s democracy crisis is rooted in a crisis of agency, in that most Americans rarely, if ever, experience themselves as having the collective ability to change the world they live in. Or, to put it in a simpler vernacular: people don’t give a shit because they don’t think they matter. And too often, the civic and advocacy groups that could bring individual Americans into something larger focus on simply getting them to take modest, individual actions – to vote, to recycle, to sign a petition, to give $3 – rather than inviting them into collective action and shared leadership.

This isn’t a new insight, and indeed the FTF report leans heavily on the research and advocacy of people like Hahrie Hahn, Elizabeth McKenna, Jane McElveny, Ziad Munson, and Joy Cushman, some of which I’ve previously covered here and here. You could add people like Becky Bond and Zack Exley, who explained in their 2016 book Rules for Revolutionaries: How Big Organizing Can Change Everything how asking people to join together in a bold transformative movement was as likely to gain participants as the technocratic “ladder of engagement” theory that imagines you have to start with very small asks before people will take on something hard.

FTF’s report argues that “Bigger We” organizing groups all embrace six elements: “a culture of agency; culturally relevant on-ramps; belonging before belief; a honeycomb structure; a commitment to bridging across the commons; and a shared long-term power project.” Each of these elements cut against the grain, not just of most short-term transactional projects and campaigns, but of the larger realities of American life. To wit:

-A culture of agency means focusing on developing people “as collective actors in public life.” Not as consumers, or mere taxpayers, or atomized individuals anesthetized by endless forms of cheap entertainment.

-Culturally relevant on-ramps means meeting people where they are and appealing to them on the basis of shared identity, experiences or interests. For political organizations this is especially hard to do because they often ask people to do hard and boring tasks rather than anything fun or engaging. And, as noted above, many other forms of social engagement like rooting for a sports team meet similar human needs for belonging while keeping people from doing anything more collective than making a “wave” during a ballgame or complaining about bad trades or coaching decisions on a sports show.

-Placing belonging before belief means welcoming people who haven’t read all the right books or know the right words to use. This is a really important distinction, one that organizers like Jonathan Smucker have been talking about for years. It’s also tricky terrain for a major funder--is FTF suggesting that it doesn’t want groups to lead with land affirmations and declarations of preferred pronouns?

-A honeycomb structure means getting to scale by networking many small groups rather than what many organizations do today, which is build a big email list or social media following. As the report states, Bigger We organizing constantly asks the question, “What is the smallest reproducible unit in our organization, and how are we investing in that?” (Paging Seth Godin, who has been trying to get organizers to understand this kernel of wisdom for years.)

-Bridging across the commons means involving all those disparate groups regularly in convenings where everyone learns to appreciate their differences as well as how to bridge them. FTF suggests that this can include things like a central leadership team meeting or an organization-wide retreat, but in my experience such practices are truly rare (and expensive and difficult to pull off), and more often than not they are rationed out to give a few lucky members and some privileged patrons the experience of being “on the inside” of a group.

-Finally, having a shared long-term power project means trying to win meaningful results over a long period in ways that grow “the shared power of the honeycomb.” Or, again to use more common vernacular—involving people in a sustained movement for change.

A Bigger We offers an expansive vision of what could be possible if committed philanthropy put $100 million a year toward such a strategy (a sum, one should note, that is a tiny fraction of the $4.5 billion that was spent in 2024 on TV ads by both sides):

“One could imagine powerful, multiracial configurations in fifteen states supported by fifteen hundred nested teams where community leaders experience the belonging, agency, and power to strengthen their resolve to make pluralist democracy work. Talent shifting flexibly across the ecosystem to stand up new efforts, meet new challenges, and build the future we all deserve. One million people in weekly non-violent actions at a scale big enough to force a moral and economic crisis to bring about change.”

Count me intrigued but also a tad skeptical. One problem A Bigger We doesn’t address is the distorting effects of Big Philanthropy on the people, organizations and movements it aims to buttress. The report kind of skirts this concern by suggesting that philanthropists back capacity building networks in order to train more organizers, fund more research into the field of Bigger We organizing, and look for ways to help organizations “test new approaches to building independent revenue streams.” It also suggests funding entities that can act as an “operational spine” for groups, taking on back-office needs and administrative burdens—something that a variety of fiscal sponsorship groups often do already. Those moves could be certainly be helpful; progressives lack leadership development institutions that operate anywhere close to the scale of the Leadership Institute, which has an annual budget around $45 million, roughly twenty times as big as the Midwest Academy.

Finally, and very helpfully, A Bigger We urges a shift in how funders and organizers measure their impact. Building on earlier work by Elizabeth McKenna and Joy Cushman, the report offers metrics to replace things like contact attempts and digital impressions, including tracking things like “number of leaders with clearly defined roles and responsibilities,” “number of chapters,” “number of teams,” “number of house meetings,” “rate of retention of members over time.” It also offers a list of ways to discern if an organization is genuinely working on long-term power building. For this list alone of metrics and questions that can be used to tease them out, plus all its other insights, A Bigger We should be required reading across the entire do-gooder universe.

Why? Because in most places…

Vu Le, the founder of the Nonprofit AF blog, who has long been one of the most trenchant and frequently hilarious observers of the dysfunctions of philanthropy, has a new book out with the surprisingly tame name Reimagining Nonprofits and Philanthropy. His critique aligns closely with the thinking on display in A Bigger We, and I just want to end this post by quoting his description of how most of the sector still behaves, despite the authoritarian power-grab underway.

“If Lord of the Rings were set in our sector, here’s what it would look like:

The elves, who hold the most power and resources, decide they’re only going to give out 5 percent of their riches to fight Sauron, maybe increase it to 6 percent, and keep the rest in their endowments, since they are immortal beings who plan to leave for the Undying Lands of Perpetuity, where none of Sauron’s actions really affect them.

Gandalf thinks the best way to fight Sauron is to gather a fellowship of brilliant warriors—so they can spend the next three years researching which communities have been most hurt by Sauron. They release a white paper and hold a summit. The first recommendation in this white paper is…to do more research.

Aragorn’s Council of Advisors believes it’s “mission drift” for him to form an army to fight Sauron, since his focus has been to be a ranger and protect the forests. Fighting Sauron is “too political” and that’s just not something they think he should do.

Boromir thinks maybe it would be best to work with Sauron, meet him in the middle; he can’t be that bad, and it’s good to have diverse perspectives; the important thing is that everyone is civil with one another and with Sauron when they disagree.

Gollum, meanwhile, is a consultant teaching people how to raise money to fight Sauron, using traditional tactics that center the emotions and whims of donors, despite Sam and Frodo saying these tactics strengthen Sauron’s power. “Why do they hates the old ways of fundraising, Precious? The old ways works! They raises money, Precious!! They keeps us employed!”

Notes on The Defiance

—Chicago is teaching the rest of us how to respond with solidarity as Trump’s ICE and CBP rampage through the city. Here’s an excerpt from a great article in (of all places!) The Chicago Tribune:

“For the past two months of President Donald Trump’s so-called Operation Midway Blitz, federal agents have engaged in a norm-defying assault on the Chicago area. In Little Village…restaurant doors have remained locked and business along 26th Street has slowed.

The resistance born there, though, has spread. A movement that began in Chicago’s Latino enclaves has arrived in neighborhoods everywhere, breaking through segregation and boundaries long defined by race and socioeconomic status. A city known for its resilience and a take-no-nonsense attitude has found another reason to unite

And in its unity, the city has made a statement, an unmistakable message akin to the one a woman packing whistles at a recent “Whistlemania” event on the Northwest Side hoped to send. “Show ’em that you don’t (expletive) with Chicago,” she said.

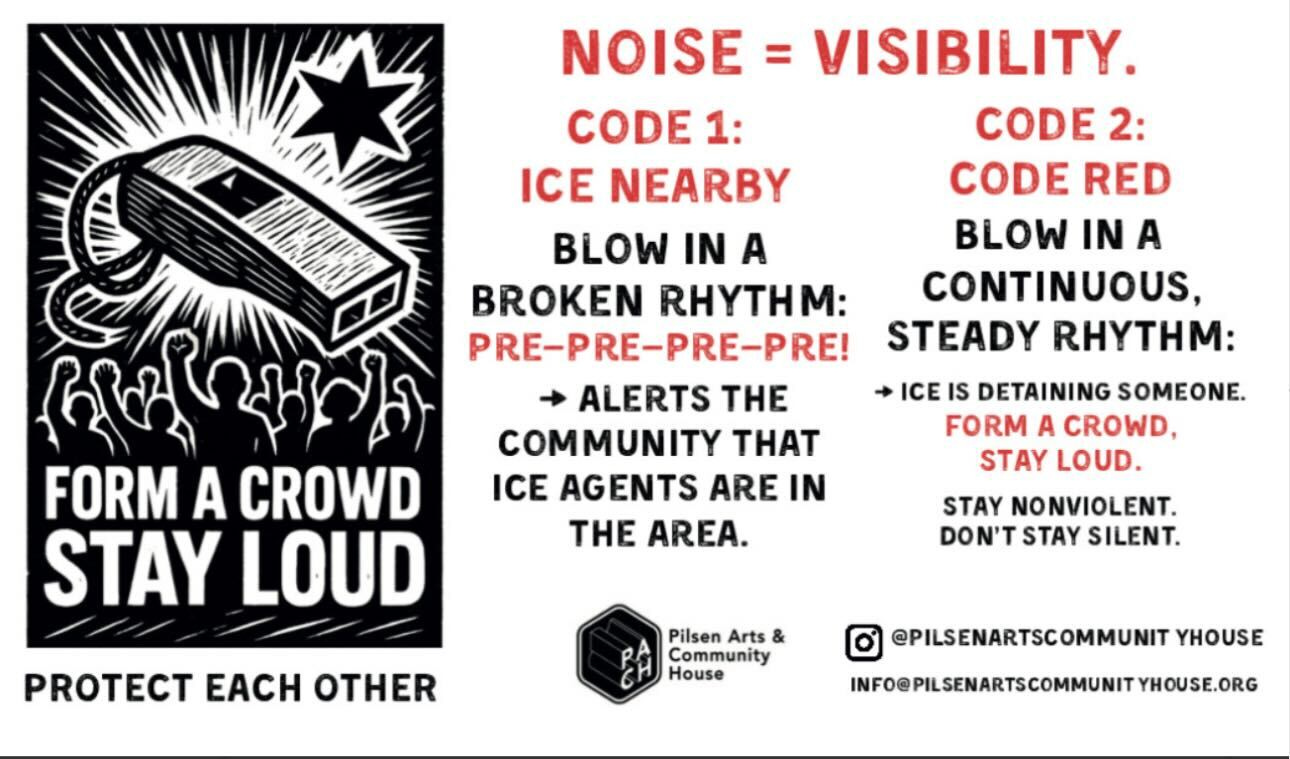

—This story in Block Club Chicago describes how people put together more than 17,000 whistle kits for Chicagoans to use to alert neighbors.

—Here’s a Google Drive folder put together by Belmont Cragin United, a neighborhood group, on how to organize a Whistlemania (or Safety Whistle event). And here’s an Amazon Wish List for buying all the supplies needed.

—What’s next on the national stage? Check out We Ain’t Buying It, a new push aimed at three major corporations that have been complicit with the Trump regime: Target, Amazon and Home Depot. Organizers are calling for a pause on shopping from these three giants from Thanksgiving through Cyber Monday.

FTF's plan sounds a lot like what Indivisible has built - thousands of local chapters united by shared values who take a variety of power-building actions together including protests, mutual aid, and winning elections. And it didn't take philanthropic millions to launch Indivisible - it took a google doc.

Indivisible was the lead organization behind both No Kings marches that broke records for nationwide protests. Which leads me to wonder why Indivisible doesn't get the credit and respect it deserves both from organizers and organizing theorists.

thanks for this clear set of observations , analyses, and suggestions for where and how to go forward. Organization is pretty much everything and calls for careful planning and implementation.

(And I think you meant to write Jane McAlevey)