New Trends in Political Tech

Parsing Higher Grounds Labs' annual landscape report. Plus, how one big VC firm is making some "radical" bets on civic tech startups. (Not.)

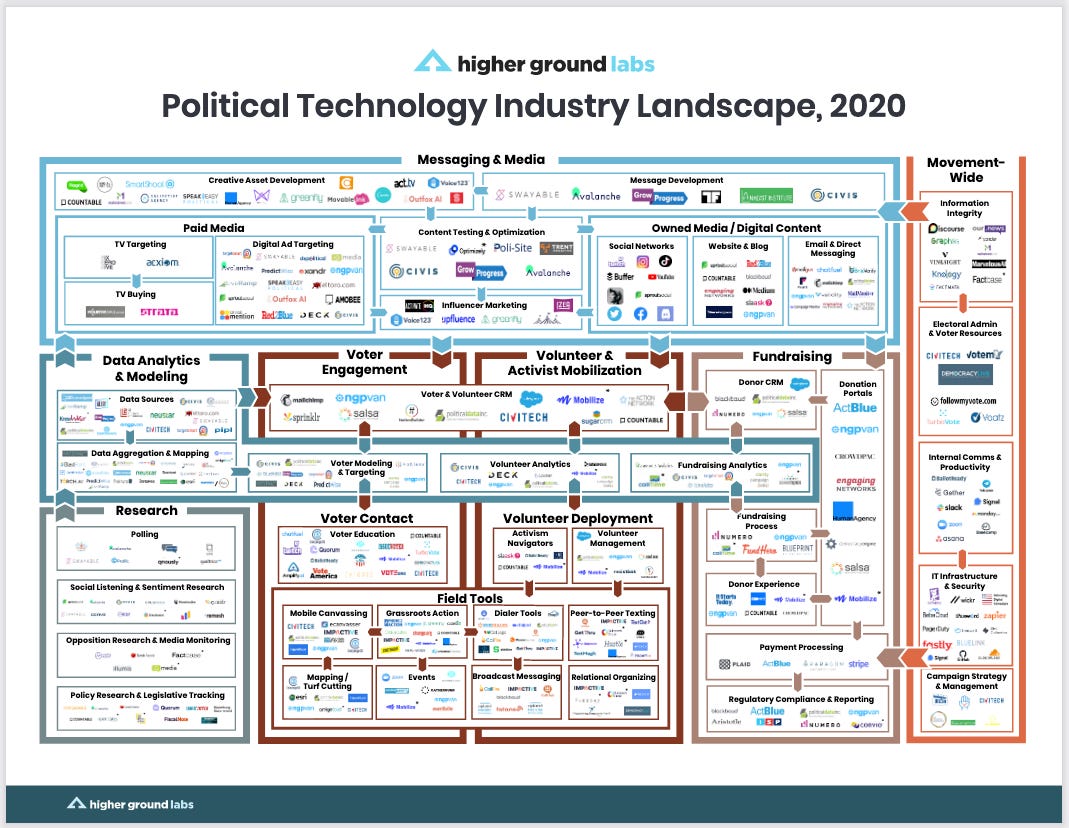

The team at Higher Ground Labs (HGL), a progressive technology accelerator founded in early 2017 that has invested $20 million since then in 36 startups that build tools, data, analytics and other tech for the Democratic ecosystem, recently posted their annual Political Tech Landscape Report. If you work anywhere in or near the arenas of messaging, media, analytics, voter engagement, volunteer mobilization, fundraising or field organizing, it’s well worth a close read. Here are my takeaways.

In his introduction, report author Teddy Gold, a former investment banker who leads investment for HGL, offers a mostly positive overview on a very challenging year: “The 2020 campaign cycle was unlike any other in modern history. COVID-19 forced candidates to make their case online, an unhinged president staged a coup on democracy, and social media platforms wrangled the effects of toxic disinformation. For an industry that was slow to adopt digital tactics, COVID-19 was the ultimate accelerant for political tech. Tech spending in the 2020 election more than doubled for both Democrats and Republicans, and a new class of startups - many minted in the aftermath of the 2016 election - were well positioned in this tectonic shift.”

While Gold is broadly optimistic about the role of tech in politics, noting how many small venture-backed start-ups have helped fill gaps exposed by COVID, and how the Democratic National Committee has, after years of false starts, made big leaps to improve data sharing among state parties, campaigns and independent groups, he also notes some challenges. “Granular voter data remains fragmented and largely inaccessible to smaller campaigns and causes. Meanwhile, the tech monopolies like Facebook and Google hold unregulated power over the most important avenue for modern message dissemination.” He also adds, “Beyond technical obstacles, the progressive movement just also reckon with organizational barriers that knee-cap its data operations. Black, Brown and Indigenous Americans continue to be underrepresented in both political data sources and campaign data teams. The success of the progressive movement in the years ahead will hinge on how well it can combat these issues of exclusion and bias. In addition, small organizations and campaigns often lack the technical expertise to build efficient and effective data programs, and the consolidation of data assets by party-affiliated groups raises questions about access and control.”

Indeed the growth and consolidation of the political technology field should also remind us of questions about who and what all of this is for. HGL’s tag-line is “We’re in the business of saving democracy.” But unless you think the entirety of democracy is winning campaigns through the ever more effective use of high tech, HGL’s Landscape Report comes up short. As Democrats continue to look back at 2020 and ahead to the battles of 2022 and 2024, there are a couple of subterranean arguments underway about, let’s face it, the sheer narrowness of their victory.

One is over the relative abandonment of face-to-face field organizing due to the pandemic. Unlike Republicans, who following their insane leader continued to hold mass rallies and door-knock, most Democratic campaigns shifted entirely to virtual campaigning. HGL’s report celebrates this shift for how much it accelerated the embrace and expansion of digital tools and platforms. However, friends of mine in the deep canvassing community, like Changing the Conversation Together, which ran a big effort in eastern PA last cycle, continue to assert, with evidence, that face-to-face door-knocking not only could be done safely but that it was still the best way to rally voters toward the Democratic column. (See also the Texas Democratic Party’s post-mortem on 2020, which bemoans the lack of door knocking as a factor in its challenges there.)

HGL’s report does nod briefly toward important research by David Broockman demonstrating the effectiveness of deep canvassing, but it is much more tilted toward high-tech. And whether or not Dems did well in 2020, many political tech start-ups did. According to HGL, with big incumbent vendors like EveryAction/NGPVan and Political Data, Inc ramping up their acquisition activity, “In 2020, the media political tech valuation was ~6.5x revenue, up from ~2.5x pre-2018.” Translation: some political tech founders made bank.

A second argument that HGL skates past is over how much Democrats spend on media advertising (and related messaging testing and strategy) as opposed to actually creating and supporting media. Tara McGowan, the cofounder of ACRONYM, a well-funded digital advertising agency, is one leading voice making the case for building more progressive media, and in the last cycle she founded Courier Newsroom to run a network of digital newsites in eight swing states. New Media Ventures made some bold choices in its latest funding round, picking several niche media efforts as worthy of more support. And Accelerate Change, a nonprofit media lab led by Peter Murray is also driving experimentation in this area, backing partners like PushBlack, Noticias Para Inmigrantes, Pulso, ParentsTogether and La Alianza. But the landscape report doesn’t explore these efforts much—is media not tech?

While HGL celebrates the big jump in spending on tech-enabled messaging and advertising, its 2020 report shows a fairly modest increase in spending on voter engagement, volunteer mobilization, or organizing and movement tech tools. HGL addresses this in part by urging a bigger investment in “effective persuasion between cycles.” Gold writes, “Advertisers know it takes a long time to build brand loyalty—car companies start marketing to kids years before they ever get their driver’s licenses. In politics, however, organizations concentrate the vast majority of their marketing in the few months before the election. While these campaigns may succeed in swaying a few indecisive voters, they are unlikely to persuade substantial numbers of disillusioned or conservative-leaning individuals to cast votes for progressives. If the movement wants to build a culture of civic participation and expand its base in a sustainable way, it must invest in more consistent, long-term messaging and media campaigns. Deep canvassing and relational organizing may be especially effective in healing the nation in the post-Trump era.”

Amen to that, though as I have been writing a lot here lately, the last-mile problem in the battle for hearts and minds isn’t going to be solved with better targeted messaging, or relational organizing that is actually more about mining supporters’ social networks instead of actual community building.

If money is the mother’s milk of politics, data on individuals is its lifeblood.

A third issue that dances around the pages of HGL’s report without ever getting resolved is the problem of privacy. On the one hand, political tech practitioners know that there’s a backlash underway against Big Tech and surveillance capitalism. On the other hand, the hard-core campaigners who are the main consumers of political tech love what they can do with microtargeting. Moves by Google and Facebook to limit online political advertising in 2020, or—the horror!—phase out the use of third-party cookies, limiting campaigns’ ability to target online, are generally seen as threats to the sector, even if they may be good for the health of democracy.

Admirably, Gold writes, “As policymakers debate the future of privacy in the United States, it is critical for the movement to create a set of best practices around data collection and distribution. Today, progressive campaigns and organizations collect an immense amount of data on voters, ranging from general demographic information to more intrusive details like geolocation. The industry is largely self-policing, which creates opportunities for abuse and harm. Setting standards for how sensitive personal data can be collected, secured, and shared — like limits on list swapping, for example — will not only mitigate risk, but also set an example for other socially conscious organizations in the public, private and nonprofit sector to follow.”

I’m not going to hold my breath expecting the progressive tech industry to take the lead here. If money is the mother’s milk of politics, data on individuals is its lifeblood. And while the spread of connective technology was initially a liberating force, enabling individuals and groups to self-organize and gain voice beyond the power of the dominant, capital-intensive world of pre-Internet, the big driver of investment in political tech has been top-down national campaigns and parties, along with the vendors who have figured out how to make money servicing that beast. Campaigns have been abusing individuals online for decades now. Outraged by the Trump campaign’s use of dark patterns to hook donors into making multiple gifts without their knowledge? How about the way Democratic vendors use hysterical subject lines to scare elderly liberals into coughing up more dough?

As Ethan Roeder, the head of data analytics for Obama 2012 said at a conference I attended on “Data-Crunched Democracy” in early 2013, “Politicians exist to manipulate you and that is not going to change, regardless of how information is used.” He continued: "OK, maybe we have a new form of manipulation, we have micro-manipulation, but what are the real concerns? What is the real problem that we see with the way information is being used? Because if it’s manipulation, that ship has long since sailed." The bottom line to Roeder was clear: “Campaigns do not care about privacy. All campaigns care about is winning.”

That said, if winning is the goal, Gold does admit that there’s a problem in how weakly organized the Democratic base actually is, based on how the most motivated activists vote haphazardly with their wallets. “Today, dollars tend to flow to candidates that receive the greatest media attention instead of those most in need of donations. This creates inefficient situations where high-profile long-shot candidates are flooded with funds while low-profile competitive candidates find themselves strapped for cash. For instance, Jaime Harrison, the Democrat who ran to unseat Sen. Lindsey Graham, raised a record-breaking $131 million, but lost his race by more than 10 points. Similarly, Democrat Amy McGrath lost to Sen. Mitch McConnell by nearly 20 points despite raising a staggering $94 million. Had that money been spent elsewhere, like competitive House and state-level races, progressives would have likely gained more seats across the country. Perhaps the greatest asset of the progressive movement is its army of small donors. Today, we see a pressing need for tools and strategies that can help the movement inform and mobilize that base for maximum effect.”

I’d add: Not just tools and strategies, but a well-informed base rooted in its own indigenous, high-quality independent media and community spaces.

Related: General Catalyst, a venture capital firm best known for its successful investments in companies like Deliveroo, HubSpot, Snap, and Oscar Health, has announced a new investment vertical it is focusing on—civic technology. Principal Katherine Boyle, who is leading the firm’s focus, told Fortune, “We think civic technology is going to be a growing sector.” Such companies, she says, are “either working hand-in-hand with the government to solve problems, or building in a way that augments the function of government to help society.” But look more closely, and it seems General Catalyst is really more interested in companies hoping to make money off of increased government infrastructure spending, or start-ups seeking to “disrupt” that sector by creaming off its most profitable parts, or worse, companies that help strengthen the police state.

So for Boyle, investee Mark43, a police tech company that provides cloud-based records management and computer aided dispatch, is civic tech. (I’m fascinated to learn that co-investors in that company include Spark Capital, Ashton Kutcher’s Sound Ventures, Bezos Expeditions, Goldman Sachs, and General David Petraeus.) For Boyle, investee Anduril, a startup that is building AI-powered surveillance and defense systems like interceptor drones for the US military, is civic tech. (Its cofounder, Palmer Luckey, the creator of Oculus, was ousted from Facebook in 2017 in part over a donation he made to a pro-Trump group.) Evolv Technology, which uses advanced sensors and AI to protect visitors at events and venues from concealed weapons, is civic tech. Samsara and Applied Intuition, which help owners of car or truck fleets manage them more efficiently, is civic tech.

A blog post by Boyle announcing the new vertical nicely explains the logic of these choices, helpfully showing how easy it is to bend words inside the looking glass. She writes: “Startups are a political protest. A small faction of people, disgruntled but determined, leave the relative comfort of an ideology or way of live to build something different. Often, they are radicals—headaches for the defenders of the status quo.” OK, maybe. “Silicon Valley has long been very good at building culture.” Say what? “Silicon Valley is [also] very good at government.” I thought Silicon Valley didn’t believe in government.

But here we get to the heart of it: Boyle writes, “as the pace of technology accelerates, so too has innovation in these sectors—and private tech companies have become instrumental to solving civic problems that government oversees. In fact, Silicon Valley—the idea, not the place—is quietly becoming a shadow capital of Washington, augmenting and replacing many of the civic functions that government used to provide. Since the turn of the century, we have watched startups usurp the responsibilities of governments at breathtaking pace: Uber and Lyft are supplementing much of public transport in major cities. Palantir has become one of the biggest complements to the U.S. intelligence community.”

Sorry, this isn’t civic tech, even if Miami Mayor Francis Suarez is nice enough to call it that. Civic tech is the use of technology for the public good, and to shift power from the few to the many. General Catalyst’s new investment arm may be making some smart investments in start-ups aimed at improving physical infrastructure uses, or solving gaps in the never-quite-successful arena of job training. But let’s call this civil engineering tech, or, in the cases of Palantir and Anduril, authoritarian tech.

-Deep thoughts: Spore drive, anyone? Francis Gooding’s essay in the London Review of Books on Merlin Sheldrake’s new book, Entangled Life—How Fungi Make Our Worlds, Change Our Minds and Shape Our Futures, is a vivid tour of the most prolific and confounding forms of life on earth. Here’s a taste: “Fungi are used to searching out food by exploring complex three-dimensional environments such as soil, so maybe it’s no surprise that fungal mycelium solves maze puzzles so accurately. It is also very good at finding the most economical route between points of interest. The mycologist Lynne Boddy once made a scale model of Britain out of soil, placing blocks of fungus-colonised wood at the points of the major cities; the blocks were sized proportionately to the places they represented. Mycelial networks quickly grew between the blocks: the web they created reproduced the pattern of the UK’s motorways (‘You could see the M5, M4, M1, M6’). Other researchers have set slime mould loose on tiny scale-models of Tokyo with food placed at the major hubs (in a single day they reproduced the form of the subway system) and on maps of Ikea (they found the exit, more efficiently than the scientists who set the task). Slime moulds are so good at this kind of puzzle that researchers are now using them to plan urban transport networks and fire-escape routes for large buildings.”