So Much Damn Money: Is That A Good Thing?

Democrats are outpacing the GOP in the new world of dark money, but their small donor base has shrunk since 2020. Plus, the data privacy debate hits one of the civic tech world's biggest players.

Welcome back to another weekly edition of The Connector, where I focus on news and analysis at the intersection of politics, movements, organizing and tech and try to connect the dots (and people) on what it will take to keep democracy alive. This is completely free newsletter—nothing is behind a paywall—but if you value it and can afford a paid subscription at any level, please hit the subscribe button and choose that option. Feel free to forward widely; and if you are reading this because someone forwarded it to you, please sign up!

“There are two things that matter in politics. The first is money, and I can’t remember what the second one is.”--Senator Mark Hannah (R-OH), 1895

“They’ve got money, but we’ve got people.”--Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY) 2020

Well, which is it? That’s the question running through my head as I ponder the following new political developments.

First, consider this front-page story in Saturday’s New York Times by Kenneth Vogel and Shane Goldmacher, which detailed how the deregulation of political spending caused by the Supreme Court’s 2010 Citizens United decision now seems to favor political organizations aligned with the Democratic Party. Sifting tax filings, they found that “15 of the most politically active nonprofit organizations that generally align with the Democratic Party spent more than $1.5 billion in 2020 — compared to roughly $900 million spent by a comparable sample of 15 of the most politically active groups aligned with the G.O.P.” Much of this money was spent on advertising, polling, research, voter registration and mobilization and voting rights legal fights. One big clearinghouse for left-leaning cash, the Sixteen Thirty Fund, which got donations as large as $50 million from anonymous donors, spent a total of $410 million in 2020 via grants to more than 200 groups, more than the Democratic National Committee. Undisclosed money of this sort outpaced the total raised by Joe Biden and Donald Trump for their own campaigns, combined.

Second, ActBlue, the Democratic donation hub, reported late last week that in 2021, 4.5 million unique donors gave a total of $1.3 billion to thousands of campaigns and organizations—twice as much as was given at the same point in the political cycle four years ago. The active Democratic donor base was almost two million people larger than in 2017 and nearly as large as in 2019. “Donors stay dedicated to fueling change” was the headline ActBlue put on its post announcing the numbers.

Third, in the last few days, Art Spiegelman’s book Maus, which was first published in 1980, has soared to the top of the best-seller lists, landing at #2 on the Amazon books list, #1 on Barnes & Noble’s best-seller list, and #2 on Bookshop.org’s list. Nirvana Books, a comic book shop based in Knoxville, Tennessee, has raised more than $80,000 to provide students with free copies of the book. This all after the McMinn County Board of Education voted last Wednesday to remove the book from its 8th grade curriculum. (My favorite donation was from someone named Nathaniel Bezanson, who gave $1,984.)

At the same time, a wave of prominent artists and other content creators have decided to pull their work from Spotify to protest its having turned a blind idea to promotion of Covid-19 misinformation by Joe Rogan, a controversial podcast host who Spotify paid $100 million to in 2020 to get exclusive rights to his show. Rock legends Neil Young and Joni Mitchell, both of whom are in the age group at greatest risk to Covid exposure, one might note, led the boycott, with Brene Brown, a TED Talk celebrity, following suit. Rogan has already responded to the pushback, promising to try to be more balanced in his discussion of the pandemic.

The fight against disinformation also keeps churning in the commercial arena led by groups like Check My Ads, which keep chipping away at online advertisers who prop up rightwing websites and causes. Right now they’re diligently bird-dogging ad executives whose companies’ ads are supporting January 6th insurrectionists.

The first two stories suggest that maybe Democrats and their allies are doing better than it appears at winning the game of politics. Especially if the second thing that matters in that game, which the plutocrat Mark Hannah couldn’t remember, is people. Perhaps.

On the question of Democratic dark money, which Rachel Cohen did an excellent job of dissecting in December in the American Prospect (and which the Times unfortunately didn’t acknowledge), the emergence of a Democratic plutosphere that may rival the Koch/Scaife/Olin/Bradley juggernaut that financed the New Right certainly means that some people may begin to enjoy a degree of financial security as Democratic activists. But when there’s so much damn money floating around Democratic power centers and so little visibility into who gets what and why, the chances that resources will be misaligned go up. Cronyism and self-dealing thrive in such conditions. Dependence on big money is now a feature of both the Democratic and Republican party ecosystems. If you think that means that mainstream Democrats will now do a better job than Republicans at responding to the needs of ordinary working people, I have a bridge you may be interested in buying.

What about the explosion in small donations that ActBlue, more than any other single organization, has helped enable? It’s true that there’s more money available to more groups, and theoretically that means a bigger universe of organizations who are less dependent on large donors. ActBlue’s report on 2021 highlights how the number of unique campaigns, committees and organizations, including nonprofits, that are getting donations has grown from under 8,000 in 2017 to nearly 18,000 in 2021. Local candidates and organizations are a bright spot, it says: “Together with local political organizations, [local candidates] raised double the amount of money and contributions compared to 2019, and 6x the dollars and 5x the number of contributions compared to 2017.”

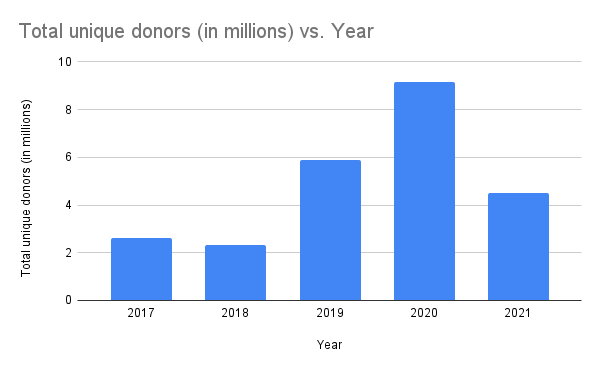

Unfortunately, the ActBlue post on 2021 skirts around a tough fact: More than half the people who made a donation via ActBlue in 2020 disappeared in 2021. Here’s how the trend looks since 2017:

Given everything else we know about the decline in President Biden’s approval numbers and the ongoing Covid-19 crisis, it’s not surprising to see that the Democratic small donor pool has shrunk since his election. Whether its fatigue or disappointment or a sense that the emergency of the previous four years is over, the high-water mark of 2020 has rapidly receded.

And yet, the current flare-ups over book-banning and Covid misinformation on Spotify suggest that there’s a lot of punch left on the left. What makes these flare-ups in the cultural arena so interesting and potentially invigorating is they allow people to vote with their pocketbooks. Electoral politics, where we only get to vote once every two years or so, is where a great deal of power is concentrated (and thus, where are great deal of organized money concentrates). Our choices in that arena are constrained well in advance by the money primary, and before that by the gerrymandering process, where politicians choose their voters. The cultural arena is a lot freer and more open to disruption. If politics is choked off by big money, activists will keep organizing cultural pressure campaigns. It turns out the dollar can vote there too.

—Related: The Starbucks Workers United union effort is making substantial gains. To date, 55 stores in 19 states have filed petitions with the NLRB to unionize.

Crisis (Again) at Crisis Text Line

From 2013 to 2020, if anyone ever asked me for an example of a civic tech organization that had achieved significant scale, I pointed to Crisis Text Line. The global nonprofit, which provides free mental health texting services in the United States, Canada and Ireland, had processed more than 105 million messages from millions of people in crisis, connecting them instantly with trained crisis counselors and undoubtedly saving thousands of lives. Ahead of many nonprofits, CTL was early to invest in using artificial intelligence techniques to help its counselors triage cases and handle urgent ones most effectivelyu. Its founder, Nancy Lublin, was a charismatic visionary who was equally at home pitching funders or wowing the TED stage. In 2016, she raised $23.8 million from LinkedIn founder Reid Hoffman, Melinda Gates, The Ballmer Group, the Omidyar Network, the Knight Foundation, Craig Newmark, Zynga founder Mark Pincus and several others. Hoffman, who was one of Lublin’s biggest cheerleaders, praised how fast CTL had disrupted the traditional world of crisis intervention. “Like other tech start ups, Crisis Text Line has demonstrated accelerating growth, and this funding will enable it to scale rapidly to deliver its critical services to many more in need,” he said at the time.

Then, in 2020, during the transformative weeks that followed the murder of George Floyd, CTL staff publicly rebelled against its erstwhile leader, accusing her of abusive internal practices and insensitivity to racial and sexual harassment, and staging a walkout. People also raised questions about the organization’s practice of calling 911 and sometimes summoning police to engage with people in crisis, also demonstrating a lack of racial sensitivity. Within a week, the board – which had received a letter from employees in 2018 detailing many concerns but never responded -- fired Lublin. Two board members stepped down and Dena Trujillo, a longtime Omidyar Network program officer who sat on the board, became the organization’s new acting CEO. (Zoe Schiffer’s story for the Verge at the time lays out most of the details.)

Now the pioneering organization is again in hot water, this time because long-simmering concerns about its privacy practices have finally boiled over. Friday, Politico published a story by Alexandra Levine reporting on how Loris.ai, a for-profit subsidiary of CTL that Lublin founded in 2018 to monetize the massive amounts of personal data it was collecting from texters in crisis, was violating their privacy. While CTL, which hoped to earn income from its subsidiary, claimed that all the data was fully “anonymized,” privacy experts question whether that was possible. Equally troubling was CTL’s claim that the people whose data it was selling had actually consented to the arrangement. “These are people at their worst moments,” Jennifer King, privacy and data policy fellow at Stanford University, told Politico. “Using that data to help other people is one thing, but commercializing it just seems like a real ethical line for a nonprofit to cross.”

At first, CTL’s CEO Trujillo responded to the Politico story with a statement defending its data practices, insisting that all personally identifiable information was removed, and claiming that the Electronic Privacy Information Center, the independent privacy watchdog, had called them a “model steward of personal data.” Yesterday, EPIC responded, noting that it had never actually done a technical review of CTL’s practices and drawing a red line: “The fundamental problem with what CTL and Loris.ai are doing is not that they haven’t used the right words or the right data techniques. The problem is that their arrangement seeks to extract commercial value out of the most sensitive, intimate, and vulnerable moments in the lives those individuals seeking mental health assistance and of the hard-working volunteer responders. And the financial relationship between CTL and Loris.ai further undermines the trust that is essential both to their core service and to the ethical academic research framework that they have worked to establish. As CTL themselves said on their own FAQ page back in 2016, commercial use of this data is “gross” and should be a nonstarter ‘(Read: no commercial use. Never ever ever.)’. That was a good standard then, and it is a good standard now. No data scrubbing technique or statement in a terms of service can resolve that ethical violation.”

Yesterday, Danah Boyd, a founding board member of CTL, and the founder herself of the Data & Society Institute (full disclosure: I’m on their advisory board and consider danah a friend), posted a long mea culpa on the whole affair. To her credit, and the credit of CTL’s current leadership, she starts by stating that they were “wrong to share texter data with Loris.ai and have ended the data-sharing agreement, effective immediately.” What follows is illuminating and should be read carefully by anyone working at the intersection of data and ethics. For what Boyd reveals (at least, as I read her) is that her understanding of CTL’s mission convinced her that it was appropriate to use texter data without their explicit consent because, in her judgment, such uses could better help people in crisis, for example, by improving the training of crisis counselors. Similarly, because CTL sought to be available instantly to anyone in crisis, and sometimes not enough counselors were available, she supported the involuntary use of texter data to improve the organization’s triage algorithm. The notion, now gaining traction across the data privacy community, that personal consent should be enthusiastically provided, was never on their radar. (See ConsentfulTech.io for more on that principle.)

Boyd also discusses how CTL’s struggle to be sustainable influenced the board’s decision-making about Lublin’s Loris.ai subsidiary. This part of her post is fascinating, because it both describes the infuriating and unjust constraints that any do-good nonprofit faces and then embraces them as reasons for ultimately doing what she now admits was the wrong thing. To wit, Boyd notes how foundation program officers rarely offer sustaining support, always wanting their grantees to find other sources of money. Sometimes, she notes, the government offers funding, but it’s been slashing support for mental health. CTL could bill insurance companies, but not all of the people it was helping have insurance. And while big tech companies were increasingly relying on CTL as their first response for people in crisis, they weren’t committing “commensurate (or sometimes, any) resources to help offset that burden,” she notes. So CTL’s board let Lublin start Loris.ai as a for-profit subsidiary (with funding from Pierre Omidyar and former LinkedIn CEO Jeff Weiner). Boyd says she voted in favor because she hoped it wouldn’t just be able to generate income for CTL, but because she believed it could train more people to develop crisis counseling skills and then “perhaps the need for a crisis line would be reduced.” And on such thin reeds of hope and infused with the can-do spirit of Silicon Valley, bad decisions were made.

Looking at the Crisis Text Line/Loris.ai mess as a whole and thinking about the nonprofit sector’s constraints and contradictions, I’m left wondering, what if we had all said that helping people in crisis with volunteers and AI was a giant fantasy, and that instead of selling that fantasy to foundations and rich tech bros and the public, which loves a feel-good story, we had said that the mental health crisis in America couldn’t be solved without massive government support, more progressive taxation, higher minimum wages, more counselors in schools, and so on. What if after demonstrating the need for more and better intervention services, CTL had organized the people it was trying to help to march on their state capitols instead of imagining it could scale up to replace government and somehow find a sustainability model that didn’t cross any ethical lines? What if would-be funders didn’t bring their flawed ideology of “blitzscaling” and working “around” government rather than “with” government to infect so much of the sector? What if instead of pretending the problem of people in crisis could be addressed with a 24-7 text line, we admitted that CTL’s tech upgrade was just another bandaid, not a cure? It’s an old story, isn’t it, social work instead of social change.

Democracy Watch

—More than 80 American civil society organizations have written the Biden Administration, urging that in the wake of its December global “Summit for Democracy” that it actually engage with domestically focused groups working on topics relevant to its themes, “including racial justice, voting rights, and fiscal transparency,” noting that these groups “were either not aware that the Summit was taking place, did not think the Summit was relevant to their advocacy, or did not know how to engage with Summit organizers.”

—Related: Tim Noah makes a cogent case in The New Republic that the catastrophism about the end of democracy in America is overwrought, and liberals should recognize that they have plenty of effective avenues to beat back Republican attempts to subvert the elections ahead.

—Amazing how three retired election technologists based in Arizona were able to use their smarts and the available public record to completely debunk the “Cyber Ninjas” and their spurious audit of the 2020 election there.

—People with faster internet connections may spend less time in civic participation, a study in the Journal of Public Economics finds. It compared information about data speeds with two major British surveys of household behavior and found a 6% reduction in participation in organizations like political parties, unions and professional associations the closer someone lived to a high-speed internet service. Maybe so, but correlation ain’t causation.

Odds and Ends

—Funny how little debate there’s been on the center-left about how close President Biden is to getting us into a quagmire in Eastern Europe with his movement of troops and armaments to counter Russia’s moves near Ukraine. Seriously, when exactly did we all agree that NATO had to patrol Russia’s borders? My friend Marc Cooper raises excellent questions in his CoopScoop newsletter, and this piece by historian Jordan Michael Smith in The New Republic gives a concise counter-history on what could have happened after the collapse of the USSR instead of the current revival of the Cold War.

—Here’s a map visualization of the 886,573 known Covid deaths in America, courtesy of Democracy Labs.

End Times

—Christian prayer apps are selling their users innermost thoughts to data brokers and companies like Facebook, Emily Baker-White reports for BuzzFeed. And some of Silicon Valley’s biggest VC firms are cashing in, like Reid Hoffman’s Greylock Partners, an investor in Pray.com; Andreesen Horowitz, an investor in Glorify.com; and Peter Theil, a backer of Hallow.com. Facebook itself also has spun up a new tool called prayer posts. “Once a prayer request has been posted, group members can choose to indicate they’ve prayed, react, leave a comment, or send a private message," Facebook said as it rolled out the feature. With church attendance in steep decline, is this the future of devotion? Baker-White reports, “Religion scholars noted that the most spiritually important conversations may not always be the most commercially viable ones, and that companies’ desire to capture users’ attention might narrow the themes explored in their devotional practice.” Might?

I am now writing twice a week for Medium as part of their contributing author program. If you enjoy the mix of topics that I cover here, then please sign up to be a Medium member. Here’s a “friend link” to a recent post about how Republican gaslighting about January 6th is even making inroads among some Democrats.