The Climate Emergency and the Better Future That is Still Possible

Wrestling with the apocalypse, with the help of the new book "I Want a Better Catastrophe" and fresh thinking about the transition we're living through.

As soon as I heard that Andrew Boyd had published a new book, back in early June, I rushed to buy a copy. I’ve known and been friends with Andrew since at least 2000, when he was the main instigator of the agit-prop project Billionaires for Bush (or Gore). Under the moniker “Phil T. Rich,” he and a merry band of pranksters would dress up in top hats, tuxes and evening gowns and then show up at campaign events, typically standing across the street from (more obviously) liberal protestors chanting things like “Let workers pay the tax so investors can relax” and holding signs reading “Corporations are people, too!” (In 2004, the group resurfaced as Billionaires for Bush, and their gloriously Web 1.0 website is still up!).

The Billionaires got a ton of free media attention, spawned at least 75 local spinoffs (in part because anyone could copy their satire), and most importantly, made protesting fun. During the 2004 Republican convention in New York City, they held a very memorable party on the Frying Pan, an old tugboat anchored on Manhattan’s West Side; one should never underestimate the organizing value of holding good parties.

In 2012, building on his many experiences in grassroots activism, Andrew was the lead author of Beautiful Trouble, which is still one of the best guides to transformational organizing to come out in our lifetimes. It’s more of a toolbox than a conventional narrative, filled with a mix of stories, tactics, theories, principles and methodologies contributed by dozens of veteran activists. He’s also written two very funny books that also draw on his years in movement culture, Daily Afflictions: The Agony of Being Connected to Everything in the Universe and Life’s Little Deconstruction Book: Self-Help for the Post-Hip.

For the last decade or so, Andrew’s gotten more involved in climate activism, setting up the Climate Ribbon project in 2014, attending a number of the international climate change conferences run by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, and most recently helping build the “Climate Clock” (which counts down how little time we have left to keep global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius) at the request of Greta Thunberg.

So while his new book, I Want a Better Catastrophe: Navigating the Climate Crisis with Grief, Hope, and Gallows Humor, retains much of the irony and whimsy of all of his earlier work, it is not an easy read. In fact, after I dove in to read it back in late June, when July rolled along and I went on vacation with it only half-read, I found that I couldn’t convince myself to open it again. Only now, back at work, mulling the wildfire that consumed Lahaina on Maui, looking at the news coming out of northern Canada, thinking back on the heavy smoke from the Quebec fires that smothered New York in June (see below), and sending my friends who live in southern California hopes that their homes will be spared from Hurricane Hilary, did I power through the rest of it.

Thinking About the Unthinkable

It’s really hard to think about the meta-crisis of climate change—or what we should now insist be called “the climate emergency”—isn’t it? It’s been on my mind at least since Hurricane Katrina devastated New Orleans in 2005, and certainly since 2012’s Superstorm Sandy flooded most of the New York metropolitan area, including the home I grew up in, where my mother still lives, on the south shore of Long Island. But still, this summer has felt different. Maybe everyone has a different moment when the penny metaphorically drops, and you know in your bones that reality has shifted. For me, it’s the last few weeks of massive wildfires, flash floods, and the merging of climate events so that instead of “getting back to normal” we start to know that instead this is the norm, and just the beginning of worse.

In I Want a Better Catastrophe, Andrew Boyd works hard to help us wrestle with the hardest questions: how we go on with our lives facing the devastating truth of the growing climate emergency, and, most critically, how do we go on doing what we can to change the world for the better despite the knowledge that it may be too late. That too much carbon and water vapor is already in the air, too much of Antarctica and the Arctic is melting, and too many species are on the way to extinction.

As he writes:

“Climate catastrophe is coming. We know this. What we don’t know is how bad it will be. In the best-case scenario, an unprecedented global Green New Deal rapidly transitions the world economy off of carbon, holding global temperature rise under 3 degrees Celsius. This causes large-scale polar ice melt, 12 inches of sea level rise by 2050, and major habitat disruption. We lose Miami, Shanghai, and many of our greatest cities. Tens of thousands of species become extinct. Coastal flooding and systemic crop failure lead to hundreds of millions of climate refugees, global resource wars, and partial social breakdown, but enough of us survive, and a chastened version of civilization—one that’s learned to live within sustainable limits—stumbles through. That’s our best-case scenario, if we’re being honest. In the worst-case scenario, runaway global warming of 6 degrees Celsius superheats the planet, wiping out humanity and most complex life forms.”

With this choice, he argues eloquently that we must do everything possible to limit the damage. But how do you organize for that? “Imagine the protest rallies,” he writes. “’What do we want? A better catastrophe! When do we want it? As late in the century as possible!’” Or picture door-knocking with the following pitch: “Hey, neighbor, I’m here today seeking beauty and dignity in failing to stop the inevitable. Care to pitch in?”

Before you think, no, humans can’t deal with this bleak a choice, Andrew reminds us that in the early months of World War Two, Winston Churchill rallied his country with an equally bleak message: “I have nothing to offer but blood, toil, tears, and sweat.” What Churchill offered was either the catastrophe of living in a world dominated by Adolf Hitler or Europe bombed to bits by the process of defeating the Nazis. So too can we choose a better catastrophe, he argues.

Well, yes maybe. Or, better, yes we must. But humans run mostly on emotion, not rationality, and my own initial inability to finish reading Andrew’s book is just another sign of the difficulty we have facing the climate emergency. As he says in his conversation with Joanna Macy (one of eight key interviews with climate organizers that the book is built around), “Social movements run on hope. You want to be able to invite people into something positive and meaningful, into building a new and better world, not just how to cope with a world that’s going to become unspeakably worse. Yet, if you’re paying attention to what’s happening to the planet, you know that unspeakably worse is a possibility, even a probability—if not already an inevitability, to hear some folks tell it. So, I feel like I’m constantly navigating between my private sense of doom, and keeping up a positive public face.” How do you navigate all of this in good faith, he asks.

The environmental scientists, organizers and strategists he talks to offer many answers, and if I Want a Better Catastrophe has any flaw, it’s in the swirl of multiple overlapping viewpoints and riffs that tend to blur its main point. Not everyone agrees that all is for naught, and that is the slender thread that keeps the book on the side of hope rather than despair. For my money, the most interesting person addressing the climate emergency that the book features is Gopal Dayaneni, the co-founder of Movement Generation, a grassroots think-tank in Oakland.

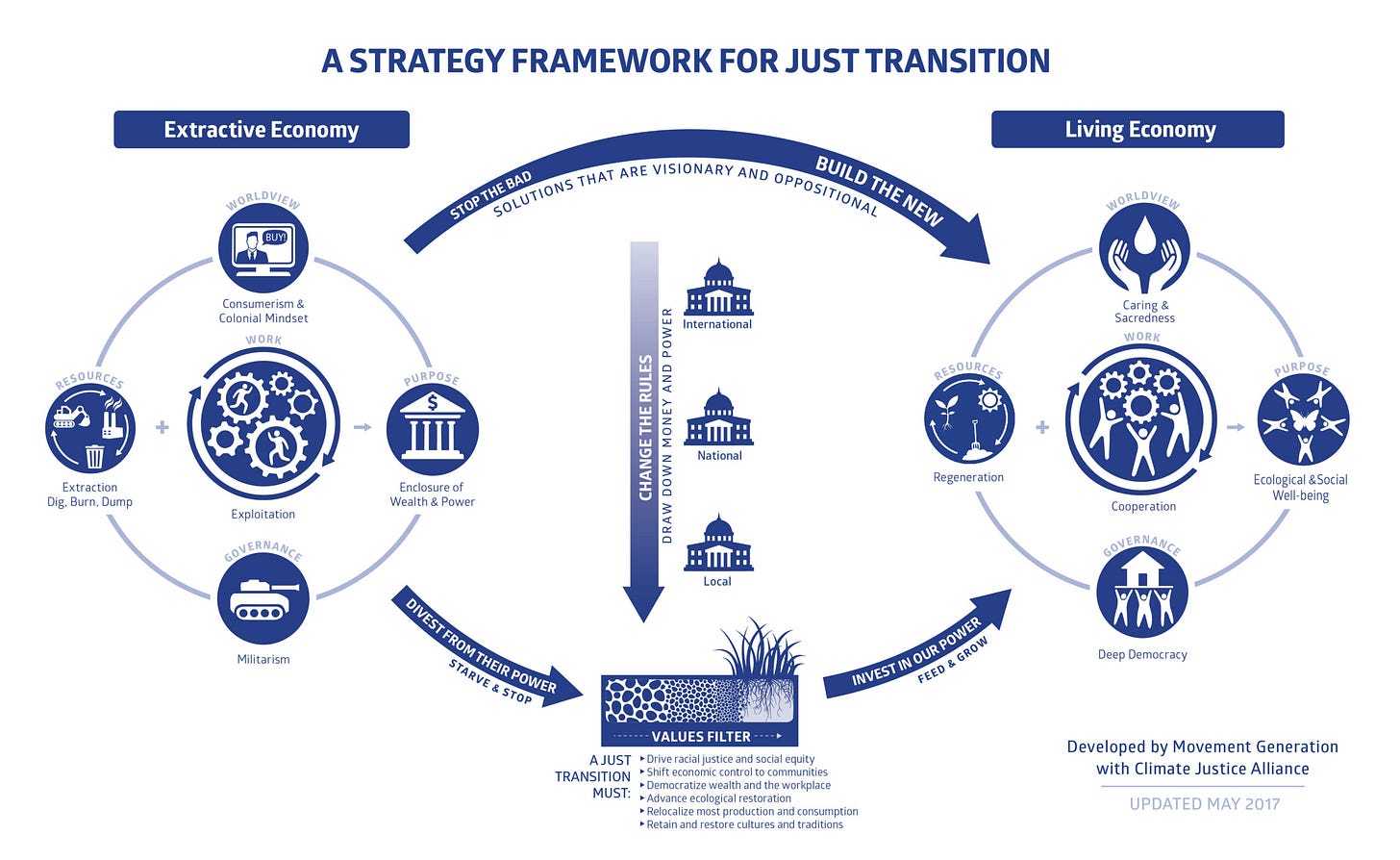

Dayaneni’s group has done some serious scenario planning and they see three paths into the future: a “Gray” one of business as usual and the evolution of a Fortress America that tries to ride out climate change with increased militarization; a “Green” one that imagines we can find technological fixes to the climate emergency without addressing the underlying exploitative system that got us here; and a “Gaia” scenario that focuses on reorganizing our economic systems around the living, natural systems of which we are a part.

Most of the current establishment discourse, which assumes creating more “growth” and “jobs” as a given, is centered on the Green scenario. “Clean energy is not a solution to the climate crisis,” Dayaneni argues, “The reorganization of the very purpose of the economy is the solution to the climate crisis. Sure, energy needs to be renewable, but as much, if not more, it needs to be democratized, decentralized, distributed, and decolonized.”

What’s so interesting and valuable about Dayaneni’s approach is that he not only is offering three plausible visions of the future, but he suggests that all three are going to happen to some extent and “our future is going to be a contest between Gray, Green, and Gaia.” To him, the dominant argument right now between the right and left over climate change (is it real, or is it a woke hoax?) is irrelevant to the actual battle over defining the solutions to come. The chart below encapsulates that understanding.

For me, this helps a lot in getting past the “it’s all over” doomerism that causes so many of us to turn away from the climate emergency, as well as the “reduce your personal carbon footprint” activism that many people try to do, even though they know it’s not enough. What Dayaneni and Movement Generation offer is a new awareness for our new normal of smoked-out cities and rising waters. We are going to go through “shocks, slides and shifts,” as Dayaneni says in the book, but instead of experiencing those as unpredictable disruptions, we should see them as opportunities. As Dayaneni puts it, “When folks say, ‘Catastrophe is inevitable,’ I think: well, yeah, but change is also inevitable; transition is inevitable….We can imagine a transition—and actually organize toward one—that both reduces our consumption of resources, redistributes them equitably, and creates greater democracy.”

“There is a future,” he says, “in which we shut off non-essential power from, say, 4pm to 7pm, so you have to go outside and play with your kids, or be with your neighbors, or whatever. There’s all kinds of ways we could socially construct the transition in a way that actually adds value to our lives, so long as we consider equity, justice, care and cooperation.”

To simplify, you might say that instead of simply trying to reduce the size of our personal carbon footprints, we have to change the direction we are walking. Strangely, even though the future may be catastrophically bad, knowing that it can also be categorically better makes me hopeful.

—Related: If you want to make a donation to support the relief and recovery effort in Maui AND also contribute to long-term community organizing and power-building, then click here to support Our Hawaii Action’s Maui fund.

Odds and Ends

—Google’s AI bots Bard and SGE are not to be trusted with their answers to questions like whether slavery was beneficial or whether Hitler was a great leader, Avram Pitch reports for TomsHardware.com.

—Food for thought: Charles Jennings, an AI startup founder and author, writes for Politico that it’s time for the US government to nationalize AI, similar to how the Atomic Energy Commission took over the development of nuclear power and weaponry after WWII.

—Say hello to the Center for News, Technology and Innovation, a new independent policy research center backed by the likes of Google, Craig Newmark Philanthropies, the Knight Foundation, and the Lenfest Institute.

End Times

Can we make Seinfeld Night a new national holiday?

In the Time's battle for hearts and mind conclusion to the three part climate transition articles we come to a Kansas solar installer who learned the hard way not to mention climate change when selling panels. "Nobody's ever going to make a decision unless it benefits them in a money sense," he says.

That's the lesson deniers operated under for ages, the one we need to import and counter with every breath we have left.