The Hard Work of Persuasion

While the Defiance keeps growing, here's an argument for moving from mass protest to lots of face-to-face engagement with people who *aren't* already in motion.

A question for pro-democracy activists: When was the last time you had a serious political discussion with someone you disagreed with? More specifically, when was the last time you talked face-to-face with someone about our current predicament, where you were trying to convince them to join you in taking an action that you believe will help stop some aspect of Trumpism, and where the person you were engaging didn’t already share your values and point of view?

I have a confession. I haven’t done that in a while. My conversations about politics are generally with people who broadly agree with me. When I find myself talking with someone who either doesn’t share my sense of our situation, or who perhaps vaguely agrees but doesn’t share my feeling of urgency, I don’t pursue them for long. In the former case, that’s often because I don’t want to expend much energy on someone who thinks what’s going on now is fine or is too apathetic, cynical, or self-absorbed to care. And in the latter case, it’s because I don’t like pushing people past their comfort zone. If someone has reasons for being less active, nagging them isn’t likely to work and it just makes you into a nag. But maybe I’m making a mistake.

I can’t prove it, but I have a feeling a lot of us are in this mode. Here’s what political activism looks like these days. Millions are going to protests like the April 5 “Hands Off” rallies or the June 14 “No Kings” rallies, or weekly #TeslaTakedown protests and pop-up protests for immigrant protection. And when we’re not doing those things, we’re going to (or organizing) meetings of likeminded souls aimed at getting more people to protest. Or we’re doing (or learning how to do) solidarity work of some kind, showing up for immigrants with legal support or ICE-monitoring. Or we’re attending giant Zoom meetings of thousands of likeminded people where a few movement leaders or issue experts talk at the rest of us, and the most interaction we do is in a chat thread that flies by too fast to read. Or we’re wasting time doomscrolling and trying to keep up with every new development in the news and every new controversy on social media. Or we’re doing some kind of grunt work for a campaign that involves brief encounters with strangers via text or phone or door-knock, but generally nothing like an open-ended political conversation about the multiple crises facing our country and world. The only exception is deep canvassing, a method of one-on-one engagement that is meant to build an empathetic relationship with someone as the foundation for a discussion about a political decision.

A glance at the list of upcoming events on Mobilize, the progressive organizing platform used heavily by campaigns and political organizations, shows lots of rallies (many of them centering on the July 17 Good Trouble Lives On protests that the “No Kings” coalition of groups is promoting as their next big national action), monthly meetings of local groups, postcarding get-togethers, visibility events involving people standing on an overpass together holding protest signs, and fundraisers. A smattering are more social, like a book club meeting organized by an Indivisible group or a “sip and paint” poster-making party sponsored by For the Many. Paging through Mobilize’s list, I didn’t see a single teach-in or event aimed at engaging people beyond the choir, other than a few canvassing events being run by local groups that genuinely appear to be trying to reach out to the unconverted. “Leafleting” isn’t even an event category on Mobilize. Neither is “deep canvassing.” (The same is generally true on the New York Progressive Action Network’s calendar and on the Movement Infrastructure Project’s DC-focused calendar and on the “Big List of Protests” calendar.)

Something tells me this isn’t going to be enough.

From Protest to Persuasion

A lot of us are working under a theory of change that can be best summarized by these two graphics.

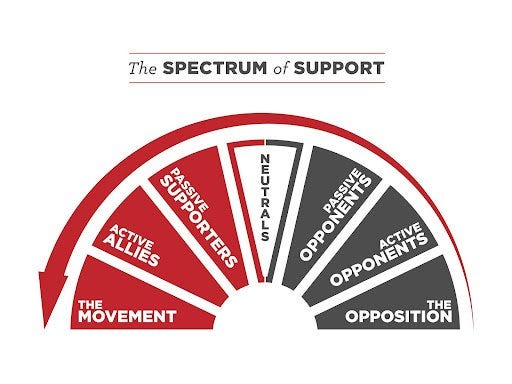

The first one, showing the spectrum of support (which I’m borrowing from Mark Engler and Paul Engler’s excellent article “Why Protests Work, Even When Not Everybody Likes Them,” argues for movement activists to devote their efforts at “passive supporters” and “neutrals.” Organizers who use this graphic often are arguing for the value of polarizing an issue in such a way that it causes people in the middle to shift in their direction, even as it may also cause support for hard-core opponents to also grow. But polarization can also cause the other side to get stronger while isolating the “movement” if you’re not careful. Rallies like “Hands Off” and “No Kings” were designed to be big tents that could appeal to a broad swath of supporters, and millions showed up. But then what?

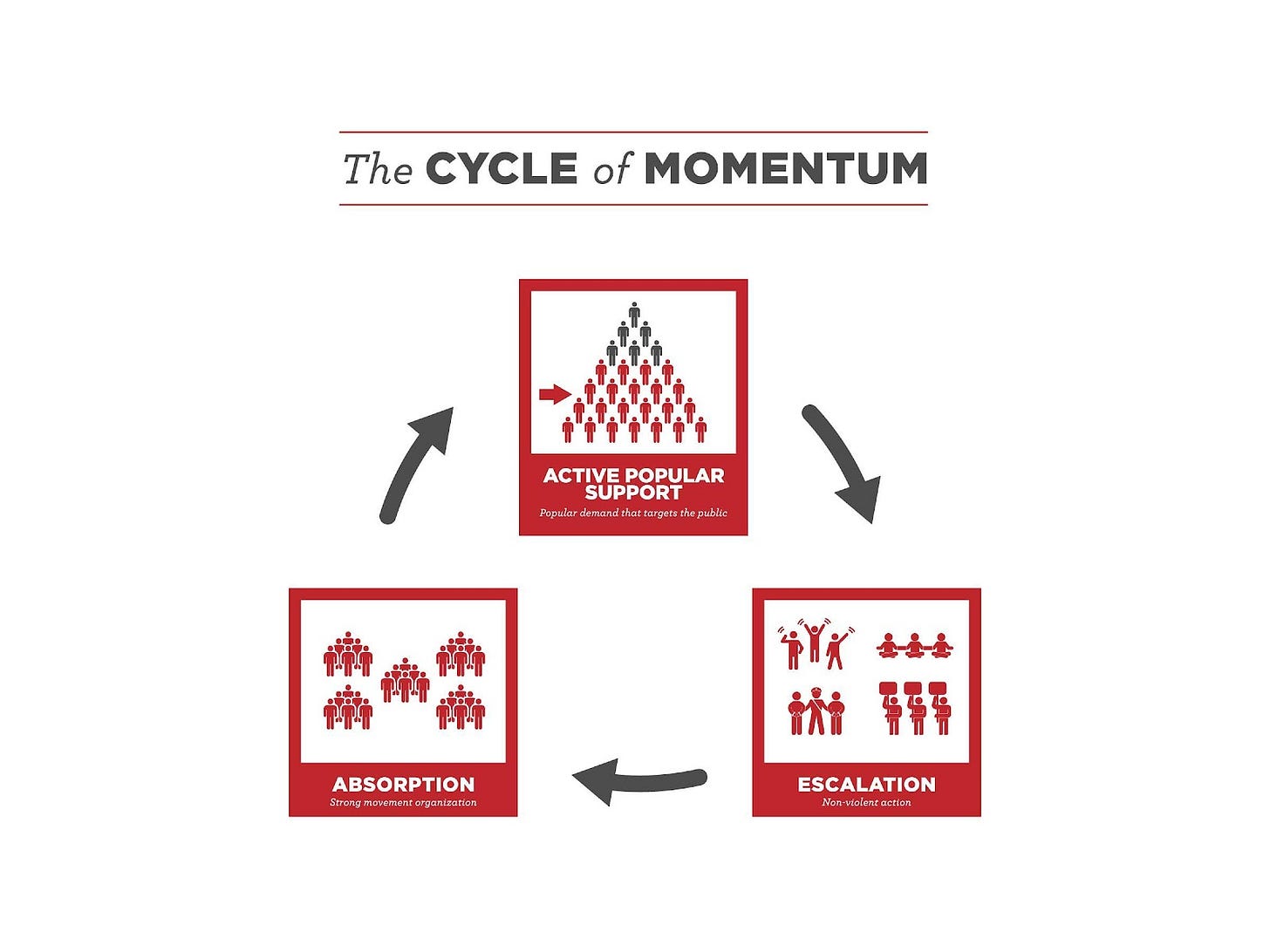

That gets to this second graphic, showing a virtuous cycle of movement growth (drawn from the Momentum organizing network’s training materials). It suggests that the period immediately after a mass protest event, which may happen because external events trigger a moral shock and spur people to action, is just as important as the protest itself. This is when new people get absorbed into an organization and, ideally, are drawn into ongoing engagement. The Momentum folks argue that this must be more than adding names to email lists, collecting online donations and social media followers. Ideally it includes inviting people to mass trainings—"when you gather a ton of newly interested people in one space where ‘trainers’ hand them the tools they need not only to attend a march, but also for each and every one of them to start planning actions and campaigns that are aligned with the movement’s strategy, vision and principles.”

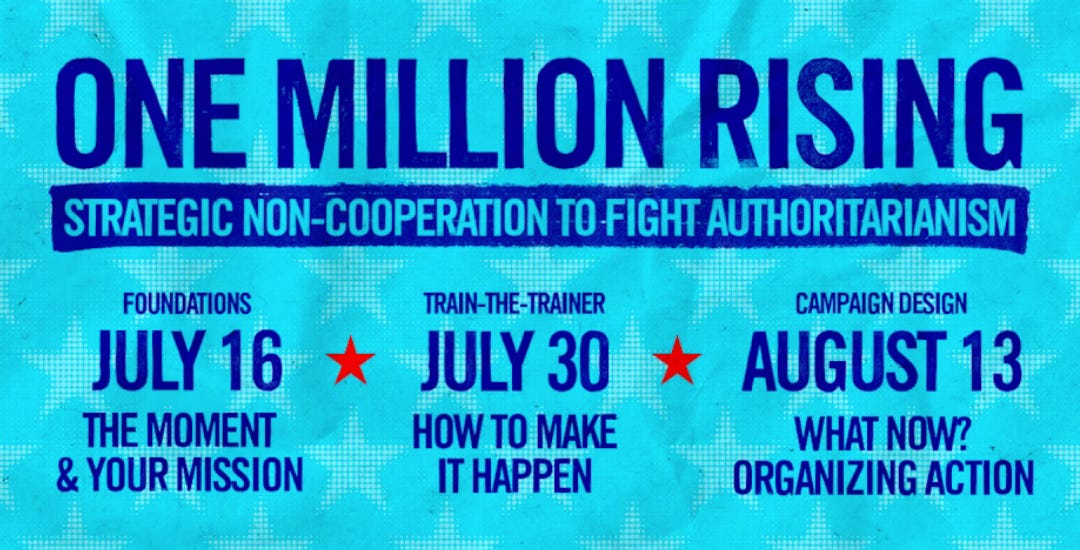

Some of this kind of work is definitely starting to happen. Next week, on July 16, Indivisible is holding the first session of a three-week online training called One Million Rising—"a national effort to train one million people in the strategic logic and practice of non-cooperation, as well as the basics of community organizing and campaign design.” The second session is the key one because that’s where attendees will be trained to train others, which is critical to scaling the whole effort. I certainly hope this succeeds. But having sat through many mass Zoom calls already, I’m worried that this form of lightweight organizing won’t produce many strong local groups or leaders.

A Blast From the Past

Let me give an example from a time before our internet-powered age of mass participation, when a relatively small group of people set out to change public opinion on a gigantic issue and faced everything from state repression to media bias and, despite the odds, grew their movement from something that was marginal and despised to something that a majority of Americans agreed with: the movement to stop the Vietnam War.

Over the weekend, I finished reading an advance copy of The Hard Work of Hope, a political memoir written by Michael Ansara that is coming out July 15. The book covers three major periods in Ansara’s life in and around the Boston area as an activist and organizer—his years as a very young and early member of the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee; his years at Harvard University where he led its burgeoning SDS chapter through many protest waves, including the massive Harvard Strike of 1969, and then saw the New Left disintegrate in paranoia, sectarian infighting and exhaustion; and then his years helping build and then lead Massachusetts Fair Share, the first of a generation of community organizing groups that eventually formed Citizen Action in 1980 and fought, often successfully, to organize working-class people and neighborhoods around progressive populist issues like fighting utility rate hikes and unequal property taxes.

It's not my intention here to write a formal review of Ansara’s book, which deserves to be placed alongside other thoughtful and engrossing memoirs of “the long 1960s” as well as the community organizing waves that followed. Someone far more versed in the intricacies of the New Left’s battles over how to end the Vietnam War would be in a better position to judge if Ansara’s version of events is fair to all concerned, or if he’s glossing over things with the benefit of more than 50 years of hindsight. Writing in Jacobin, labor journalist Steve Early praises the book for the lessons it conveys about how SDS cracked up in the late 1960s, but also savages Ansara’s later role in a mid-1990s Teamsters union scandal that, he says, triggered the collapse of Citizen Action, and raises questions about Ansara’s second career as a political consultant and telemarketer—topics that get scarce mention in The Hard Work of Hope.

Those are arguments for another day. Instead, I want to flag something else that jumped out at me as I read of Ansara’s time organizing against the Vietnam War with SDS and later organizing for community empowerment with Mass Fair Share: he and his colleagues spent endless hours working to persuade non-believers to join them. Listen, for example how he explains organizing across colleges in New England in advance of SDS's first national March against the war in Vietnam which took place April 17, 1965.

“We had to explain the basic facts about Vietnam over and over. In leaflets that we would slide under every dorm room door. Over meals in dining halls. In small groups. After classes. Everywhere we could, we explained how Vietnam, after centuries as an independent country, had been colonized by the French, how then the Japanese had occupied the country during the Second World War, and how the United States had supported the resistance to the Japanese led by the communist Ho Chi Minh. Then after the defeat of the Japanese, the attempt by the French to reassert their colonial control and the new war of independence once again led by the communists and Ho Chi Minh….Over and over, we would use this quote from President Dwight D. Eisenhower in his memoir Mandate for Change: ‘I have never talked or corresponded with a person knowledgeable in Indochinese affairs who did not agree that had elections been held as of the time of the fighting, perhaps 80% of the population would have voted for the communist Ho Chi Minh as their leader.’

We educated. We listened. We organized. We produced fact sheet after fact sheet, our hands stained purple from running leaflets on Gestetner machines, our clothes splotched, black from mimeo ink…. In the month before the March, the faculty and graduate students at the University of Michigan held the first ‘teach-in.’ Amazingly 3000 students cycled through the prolonged event. Soon SDS and sympathetic younger faculty were organizing teachings at 100 universities across the country. They were meant to be like a ‘sit-in,’ professors, teaching fellows, and students making presentations and speeches, one after the other, hour after hour. The crowded halls were filled with couples snuggling, antiwar activists recruiting the people in the next seat over, wide-eyed freshmen from conservative families wrestling with what they were hearing, a few members of Young Americans For Freedom at the doors denouncing the whole affair as a red conspiracy, and large numbers of reporters writing furious notes and doing interviews in the hallways outside....That spring opposition to the war was taking root on America's campuses.”

Or again, at the end of 1965, after a second March on Washington DC again with 25,000 to 30,000 people marching, Ansara writes:

“Each time we marched, there was a reaction against us that opened room for discussion and debate. Each march, each bus ride to DC, each demonstration, forced students to choose -- would they stay silent or would they act? Once you pinned on an antiwar button, once you passed out a leaflet, once you boarded the bus to DC, once you marched, you were committed and part of a new community of activists. Each time a student said to me, ‘I think you are wrong to protest,’ I had the chance to make the case against this wrong war, to plant a seed of doubt, share facts, and offer an alternative framework.

In the long run, real world events would prove decisive in building the opposition as the war was brought into living rooms through television in a way that no other war had been. But our organizing, educating, and constantly engaging with the young was required to create the room for dissent and build an organized antiwar movement....It is easy to write about the demonstrations, the marches, the confrontations. They were dramatic and essential, however they were only possible because of long hours of outreach, discussion, connecting. It was the mundane work of reaching out to students that occupied me and the other SDS organizers and that made it possible for people to join the march, get on the bus, join the movement. Demonstrations not immediately followed by engagement, education, and organizing would do little to build the movement....No one was changed in a single discussion. It took time and persistence. SDS distributed mimeographed leaflets in all the dorms once a week discussing the latest developments. SDS members talked, distributed newsletters, and talked more. Over and over again, we returned to the question of how we could manage to live a moral life in the face of mass consumer culture, racism, stifling consensus in support of the corporate liberal state, and, above all else, an immoral war.” [Emphasis added.]

Later in the book, Ansara explores how and why SDS activists veered into sectarian infighting, conspiracy thinking and, in some cases, support for violence—causing it to lose support, fracture and collapse just when it needed to mature into an organization that could sustain a generation moving from college into the workforce and the long march through the institutions. He excoriates himself and his colleagues for turning away from electoral politics in 1968, when they told young people that voting was a waste of time (instead of backing the flawed Democrat Hubert Humphrey against the far more dangerous Richard Nixon), and he fiercely regrets their choice to march with the flag of the Vietnamese National Liberation Front rather than the American flag, sharing how he only learned later how much that alienated many working-class young people who were themselves becoming leery of the war by the late 1960s, but also put off by the elitism of the much of the antiwar left. But even that is a lesson he learned because he was trying to organize working-class neighborhoods against the war and thrust into conversations with people very different from the red-diaper babies and fellow travelers who flocked to SDS in its early years.

As Trumpism continues to spread and shock millions into action, the ranks of Defiance keep growing. But we can’t rely simply on moral shocks to produce a counter-reaction big enough to tilt America in a better direction. (The newly passed Big Ugly Bill will produce all kinds of pain, but as Robert Kuttner argues darkly in The American Prospect, Trump and the GOP may not be worrying about a backlash in 2026 because they’re prepared to either tilt the election in advance or ignore its results in the aftermath.)

So I think we’ve got to shift from protest to persuasion and absorption. The twenty lessons that make up the body of Timothy Snyder’s essential On Tyranny are designed to help people resist rising authoritarianism and efforts by would-be dictators to intimidate us into submission. They’re all worth following. But if I could offer an addendum, I’d suggest one that is surprisingly missing from Snyder’s list: we must get out of our comfort zones and talk with people who aren’t already with us, and do it not just as isolated volunteers working through a call list, but as part of something bigger.

Federal Workers are Still Fighting

—The Environmental Protection Agency has suspended 139 employees for signing an open letter to EPA Administrator Lee Zeldin dissenting “against the current administration's focus on harmful deregulation, mischaracterization of previous EPA actions, and disregard for scientific expertise.” Public employees are protected by the First Amendment, but an agency spokesperson said they’ve been suspended as retaliation, declaring that it “has a zero-tolerance policy for career bureaucrats unlawfully undermining, sabotaging, and undercutting the administration’s agenda as voted for by the great people of this country last November.” This Wednesday at 5pm in Foley Square in Manhattan, people will be rallying to support them.

—Nineteen fired and current federal workers from 16 different agencies came together in the first coordinated interagency act of digital resistance last week, co-producing a video where they restate their oath to the Constitution (something they all do on first starting their government jobs). The video was published by the alt- accounts of USAID, NIH, OPM, and VOA, joined by Project Moonshot, We The Builders, and Feds Work For You.

End Times

I could easily get lost in this.

Can't tell you how strongly I agree with the fundamental message of this post. Will be sharing it with lots of folks.

I was a student at U of M Ann Arbor and involved in that first teach in on the Vietnam War. It was exhilarating. What we did NOT have then was well-processed Alt Facts on Tik Tok, Instagram, Facebook, websites. I can't imagine being able to do that today. I wish it not so.