The Hybrid Workplace is Here to Stay: Work Has to Evolve

But will bosses get the memo? Or are home-bound workers at the end of their ropes? A new study from Microsoft and a new book on innovative workplaces are full of warnings.

Is remote work about to end? As infection rates drop and cities reopen for business, some American employers are looking forward to getting back to their offices. But they’re worrying that a good portion of their workforce may not want to come back. Say hello to the next great disruption: after a year of flex work, a lot of the assumptions about the wonders of “Office Culture” are on newly shaky ground.

Yesterday, Cathy Merrill, the CEO of Washingtonian Media, a small business of about 50-60 employees that she inherited from her father, published a controversial opinion piece in the Washington Post, where she shared her worries—as well as those of her CEO peers--about the “unfortunately common office worker who wants to continue working at home and just go into the office on occasion.” According to her, this is a bigger problem among senior employees who are “working from comfortable homes and happy to be relieved of commuting” than younger ones stuck in small apartments or their parents’ homes. And she frets that if hybrid work is allowed to become the new status quo, businesses like hers will have all kinds of problems: they’ll have a harder time attracting new talent if senior leaders aren’t on site; leadership teams will face challenges successfully managing employees; and most intangibly, the casual conversations and creative connections that get made informally at offices will leave out home-bound workers. “There’s no such thing as a three-minute Zoom,” one CEO told her.

If you don’t see what’s wrong with Merrill’s sentiments, well, people who have led or worked in office environments for a long time better get ready, because what the Pandemic Pause has taught a lot of formerly office-bound workers is “another world is possible.” Instead of treating working from home as a temporary emergency stopgap, some businesses and nonprofits have worked hard to adapt, making employee safety and health their top priority and treating the issues Merrill raises—how to remotely mentor and manage staff, how to create opportunities for creative collaboration—as challenges to be overcome.

Others, like Merrill’s Washingtonian, are about to step in it.

Today, the Washingtonian’s editorial staff are on a one day work slowdown, refraining from posting anything online and tweeting in unison that “we want our CEO to understand the risks of not valuing our labor. We are dismayed by Cathy Merrill’s public threat to our livelihoods.” That’s because in addition to all of her tone-deaf comments about her employees, she actually threatened to demote straggling stay-at-homers in her Post piece and turn them into lower-paid contractors with no benefits.

She writes, “I estimate that about 20 percent of every office job is outside one’s core responsibilities — ‘extra.’ It involves helping a colleague, mentoring more junior people, celebrating someone’s birthday — things that drive office culture. If the employee is rarely around to participate in those extras, management has a strong incentive to change their status to ‘contractor.’ Instead of receiving a set salary, contractors are paid only for the work they do, either hourly or by appropriate output metrics. That would also mean not having to pay for health care, a 401(k) match and our share of FICA and Medicare taxes —benefits that in my company’s case add up roughly to an extra 15 percent of compensation. Not to mention the potential savings of reduced office space and extras such as bonuses and parking fees.”

Excuse me while I go gargle. I just threw up a little in my mouth.

Bosses like Merrill are walking on thin ice. According to a new study of more than 30,000 people in 31 countries from Microsoft’s Worklab, more than 40 percent of the global workforce is considering leaving their employer this year and nearly half are thinking about making a major pivot or career change. (Holy cow, I wasn’t wrong when I suggested a few issues back that a lot of us were in a liminal state.) More than 70 percent want flexible remote work options to continue, while nearly the same number also crave more in-person time with their teams. Two-thirds of business decision makers are pondering how to redesign their physical spaces to embrace these contradictory impulses. “The data is clear: extreme flexibility and hybrid work will define the post-pandemic workplace,” the report says.

Most business leaders—who trend more male and older—are out of touch with their workers (big surprise? no!). By a large margin, leaders report that they’re thriving right now. At the same time, 37% of the global workforce “says their companies are asking too much of them” right now. 54% feel overworked. 39% feel exhausted. 60% of Gen Zers, the 18-25 year-olds new to the work world, say they are “merely surviving or struggling right now.” About one in six employees overall have cried with a colleague this past year.

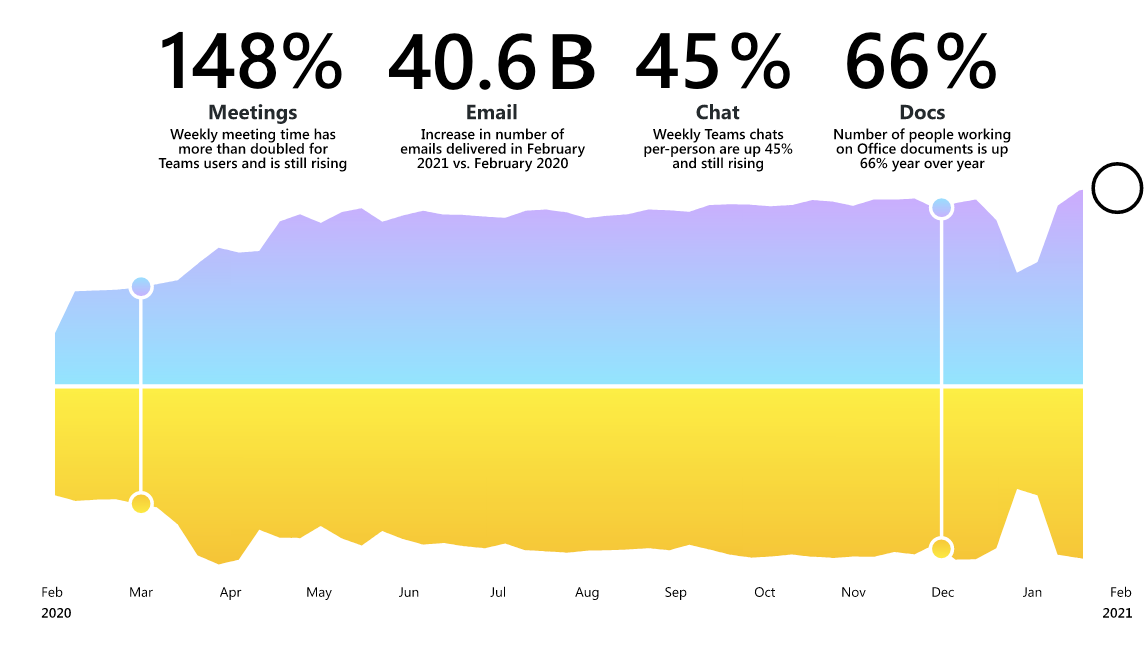

Worklab looked at “trillions of productivity signals from Microsoft 365” (yikes!) to “quantify the precise digital exhaustion workers are feeling.” They found that “the digital intensity of workers’ days has increased substantially.” The average meeting is ten minutes longer than a year ago. The average Teams user is 45% more chats per week and 42% more chats per person after hours. I could go on, but I’ve got to go respond to three new Slack prompts, brb. Oh, and, “Despite meeting and chat overload, 50 percent of people respond to Teams chats within five minutes or less, a response time that has not changed year-over-year. This proves the intensity of our workday, and that what is expected of employees during this time, has increased significantly.”

(Image from The Next Great Disruption in Hybrid Work, Microsoft Worklab. Blue is meeting minutes per person; yellow is chats per person. If you go to the original, the graph is interactive. The little dip at the end is the winter holiday break.)

Worklab’s researchers also point to a worrisome trend, which is the increased siloing and isolation of remote workers. People are tighter with their immediate teams or close networks, but even those interactions are diminishing. This is bad for all kinds of reasons, but Nancy Baym, a senior principal researcher at Microsoft, says it’s especially bad for creativity. “When you lose connections, you stop innovating. It’s harder for new ideas to get in and groupthink becomes a serious possibility.”

What to do? The Worklab report says to focus on empowering people “for extreme flexibility,” including investments in bridging physical and digital worlds, evolving team culture “to ensure all voices are heard,” addressing digital exhaustion; and more proactive efforts to build social capital and support among employees.

Ah, if only we lived in a world led by such enlightened bosses.

Several weeks ago, I found myself devouring a short book by Alexandra Deschamps-Sonsino, a independent design researcher based in London, called Creating a Culture of Innovation. It’s a delightfully subversive guide to the modern office environment with a particular focus on how what she calls the "global game of innovation theater" has evolved since the end of World War II to the present. At a moment when people are rethinking the workplace, I highly suggest picking up a copy. Because before we go back to “work,” it can’t hurt to understand, well, how did we get here?

The modern white-collar office started to change, Deschamps-Sonsino writes, with the Rand Corporation's use of inner courtyards to foster serendipitous connections between researchers. Later, in response to the security lapse represented by the leak of the Pentagon Papers (yes, that was 50 years ago next month), Rand clamped down on staff freedoms, pioneering new measures for employee surveillance that are now quite common. Then, with the rise of digital work, she charts the explosion of the "open office" format and the use of interchangeable "hot desks” where no one has a personal workspace anymore. Surveillance by management has risen the more "office spaces [have] start[ed] to resemble airports" where you can’t tell what someone is working on simply by looking at their desk.

What makes Deschamps-Sonsino’s book so enjoyable is how she slashes and burns her ways through so many totems of the so-called culture of the innovative office:

the rampant use of Post-It Notes ("the lack of real goal-setting and meeting structure when these tools are put into people's hands can make people feel like they've done something when in fact they haven't");

the reliance on cool design and furniture to signify that something innovative is happening in a space ("I'm not sure there's a correlation between a piece of furniture and productivity," the codesigner of the Aeron chair once said, she notes);

the notion that "creativity is a personality trait" and organizations are more innovative if they have a person or team with innovation in their title, or in their inflated title ("digital prophet" David Shing, aka Shingy at AOL);

why "strategy workshops" and organizational retreats usually fail;

the ways organizations over-rely on digital reporting systems like OKRs (objectives and key results) and how that can impede creative work.

Most delicious to me is how she punctures the myth of "innovation spaces" as anything more than a kind of form of tourism, "a trip to the aquarium of ideas," and a form of signaling to others that the organization cares about innovation. She writes, after offering a series of capsule case studies of Capgemini's Netherlands CoZone ("We wanted a space that was unregulated; a space in which graffiti would be considered cool rather than vandalism," its designer blogged, gargle some more) and its AI Zone in NY, SAP's Data Space in Berlin, PwC's Frontier Data Lab in the UK and Accenture's Innovation Hub, "These spaces are neither successful nor unsuccessful, but they are examples of a very particular corporate desire: the one where talking about innovation is as good as innovating."

I suspect this desire is widespread as well in the nonprofit and government sector. Take this anecdote from my time at Civic Hall. One day, NYC Mayor Bill de Blasio took over our loft space in Chelsea, along with a bunch of deputy mayors and various honchos from the NYPD, to brag about a new free digital security app that they were releasing. The app does very little -- the mayor said that if you were on a city-owned Wi-Fi network it would tell you if you were visiting a dangerous website -- but he flogged it as making New Yorkers safer than people anywhere else from cybercrime. More importantly, he flogged it at Civic Hall, demonstrating his savvy about how to signify that his administration "got" tech.

Deeper inside Deschamps-Sonsino’s book is a serious critique of the problems still inherent to the digital workplace as well as the project of fostering innovation, and some hard-won conclusions about the conditions that actually are conducive to creative work. One, which you rarely see discussed in the innovation literature, is the need for workplace equity. She writes, "It's very hard to have great ideas when you're angry at basic workplace inequalities." She also emphasizes the need for a culture of safety, where employees feel free to bring their whole selves to work and to make mistakes. Nearly every buzzword and technique now prevalent in workplace innovation, Deschamps-Sonsino, is likely getting in the way of basic prerequisites like creating diverse teams and making sure meetings have clear purposes.

For a long time, I’ve wondered if we would ever see a societal rebellion against modern digitalized work. Those of us who are older can remember when we didn’t spend a third of our time responding to work emails. But I also get why so many younger people embraced the new digital landscape; in some ways it was theirs to shape and also their supposed “fluency” offered a competitive edge. (More than years ago, I ran a breakout session at RootsCamp on coping with digital overwork and most of the younger folks in the room basically didn’t understand what I was worrying about—which was probably as much my fault as anyone else’s.) But here we are. How are you or your place of work navigating this new terrain? Are you thriving? Are you struggling? And who is doing the adapting, you or your boss? (Hit the button below to share a comment.)

Odds and Ends

-A whopping 18 million out of 22 million public comments submitted to the FCC in 2017 on its planned repeal of net neutrality rules were fake, a new report from NY state attorney general Letitia James has found. They were the product of a secret campaign funded by the country’s largest broadband companies, using lead generators, Issie Lapowsky reports for Protocol. Consumers were offered everything from discounted kids movies to free trials of male enhancement products in exchange for submitting their email info.

-Related: A new report from Free Press finds that broadband prices in America have risen at more than four times the rate of inflation since 2016. That includes their lower-priced entry-level options, which are disappearing. No connection to the end of net neutrality, right?

-Say hello to ParticipatoryGrantmaking.org, a new hub for people sharing their work, ideas and hopes for this emerging new form of philanthropy. (h/t Josh Lerner)

-Judd Legum on the Facebook Oversight Board’s decision to sustain Trump’s suspension speaks for me. I read their choice as simply this: Zuckerberg may have dropped out of college but he still has to do his homework.

-Must-read: My friend and former colleague Jessica McKenzie has a blockbuster piece in Grist on how a cryptocurrency company backed by a private hedge fund has given a shuttered coal plant in upstate New York a second life on burning carbon. There’s no demand for its electricity so after Atlas Holdings of Greenwich, CT, bought and reopened the plant, it decided to mine bitcoin instead. It’s now one of the largest cryptocurrency mines in the country.

-End times: God gets a performance review.

As always, The Connector is free to all to read. But if you are reading this because someone forwarded it to you, please subscribe. And if you can, choose one of the paid options—they’re not required but they help keep me from putting up a paywall.

Yes! I also was stunned by that piece from Cathy Merrill of the Washingtonian. One item that struck me is the idea that she has the power to demote some employee to contractor on executive whim. Unless you are Uber or Lyft and can afford to spend beaucoup millions on bespoke laws, this isn't the case. States look at employee to contractor conversions rather dimly, since it usually involves evading employer-paid taxes, and also runs afoul of IRS regulations (so, you just decided someone who was an employee and meets the IRS definition of an employee isn't one, to punish them, and stopped paying your share of social security taxes?). I'd put the Washingtonian high on my audit list if I was a taxing authority.

All I can add is that I've worked from home since 2008 and never looked back.. I loved the description of innovation theater from the book you mention and post it notes!

"the rampant use of Post-It Notes ("the lack of real goal-setting and meeting structure when these tools are put into people's hands can make people feel like they've done something when in fact they haven't");"