This Shor Smells Bad***

Why do so many Democratic politicians keep relying on bad advice on how to win elections and build power?

I’ve long wondered why David Shor, a 34-year-old data analyst and self-styled party boy, has so much influence over Democratic party debates about strategy, given that his main expertise is only in polling. Shor, who runs Blue Rose Research and oversaw Democratic SuperPAC Future Forward’s massive $560 million ad spend on behalf of Biden/Harris during the 2024 election, was one of the select few political experts asked by Senate Democrats to brief them at their annual issues retreat last spring. Back then he was telling everyone that Democrats were in a deep, deep hole, potentially generational in scope, particularly with young men and Hispanics, and that they had to tack right to win them back. Over the summer, Blue Rose was telling Democrats to avoid talking about Trump’s military takeover of Democratic-run cities because it didn’t poll well. We all know now that these weren’t permanent signs of anything, as now both young men and Hispanics are breaking hard away from Trump. Gosh, maybe you can change public opinion and not just reflect it?

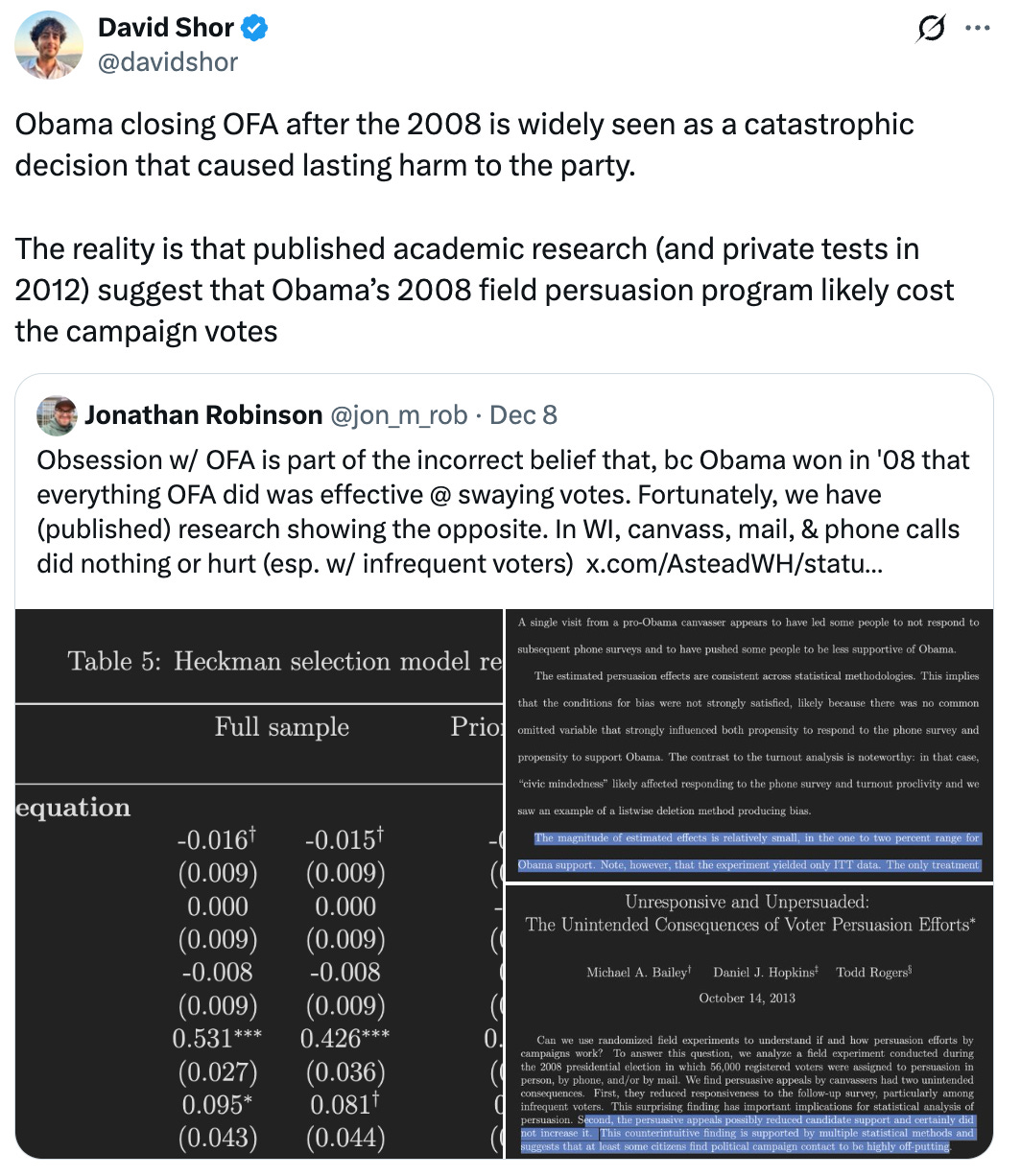

But a recent comment of his on Twitter/X ought to demonstrate how little anyone should trust Shor on big questions of strategy. Sunday, he wrote that “Obama closing OFA [Organizing for America] after the 2008 is widely seen as a catastrophic decision that caused lasting harm to the party. The reality is that published academic research (and private tests in 2012) suggest that Obama’s 2008 field persuasion program likely cost the campaign votes.”

Shor was piling onto a comment by Jonathan Robinson, another, less-well-known data analyst (who I’ve occasionally corresponded with and usually learn from, though not this time), that pointed to the same research. Robinson himself was commenting on a post by Astead Herndon, a very well-respected political reporter who is now with Vox and previously led some of the New York Times’ best coverage of the 2024 election. What Robinson wrote aligned with Shor’s condescension for the Obama grassroots network, though he was more polite about it: “Obsession w/ OFA is part of the incorrect belief that, bc Obama won in ‘08 that everything OFA did was effective @ swaying votes. Fortunately, we have (published) research showing the opposite. In WI, canvass, mail, & phone calls did nothing or hurt (esp. w/ infrequent voters).”

Now, before I dive into why Shor and Robinson are basically full of it in using this Wisconsin study to prove anything, let’s see what got Herndon’s eye in the first place, which is frankly far more important. “Caught my attention,” Herndon wrote, “@patrickgaspard on Zohran Mamdani’s discussions with Obama, and Gaspard’s regret about the decision to fold Obama for America into the DNC.” That is, Gaspard, one of Obama’s top political strategists, who served as his Ambassador to South Africa and who is today helping Mamdani navigate his way into his mayoralty, had told a group of veteran city journalists called The New York Editorial Board something very interesting about that 2008 decision to mothball OFA. To wit:

Patrick Gaspard: You know that he’s had several conversations with former President Barack Obama, my old boss. I won’t tell you the readout from those conversations, but I will say that I personally pressed him to have a dialogue with the president about what his evolving views have been about the decisions that we made coming out of the 2008 campaign to fold Obama for America, our movement that was independent of the traditional Democratic Party—because Barack Obama was not the choice, if you recall, in the primary, of the unions, of the elected officials, of their institutions.

We made a decision to fold OFA into the DNC. It’s a decision that I disagreed with strongly and I didn’t voice. I didn’t have the courage and the ability to voice my strongly held views about that. I’m not proud of the way that I held my views in that moment. [Emphasis added.] And I pressed Zohran to have a conversation with the president about his evolving sense of how he managed or didn’t manage that movement coming into his presidency, and whether or not there were ways to deploy that energy that could have accrued to our benefit as we tried to pass major legislation and tried to shift the tenor of the politics in the Democratic Party and beyond the Democratic Party. And I know that he’s had that conversation, he’s thinking clearly about what it means to hold that together as he litigates his—

Josh Greenman: And you’re talking about them doing things on the ground too, in addition to … in addition to calling legislators?

Patrick Gaspard: No, no, no. This is not about calling legislators. These are people who have skin in the game, and who are ready to go out and knock on doors again and do the thing on street corners, in front of supermarkets. And so they’re ready to be called to a purpose, and he’s ready to organize that to a constructive purpose in all the essential parts of his agenda, but also the crisis du jour that will invariably come up.

That’s the excerpt that Herndon cited in his post, which got such pushback from Robinson and Shor. It’s worth reading the whole interview with Gaspard, in part because he makes clear that he believes Mamdani feels a strong personal connection to the “104,000 to be exact” volunteers who worked their hearts out for his victory. “They came out and did a thing that is historical [and] he believes that the victory belongs as least as much, if not more to them than it does to him and those who were part of his core team,” Gaspard says.

It’s this whole package of hard work, commitment, and community that Shor and Robinson are dumping on. Responding to Shor on Twitter/X, Zephyr Teachout, who worked for Howard Dean in 2004 and later went on to run a strong primary challenge against New York Governor Andrew Cuomo in 2014, said:

“The Obama 2008 campaign chose, in the way it structured OFA, to maintain centralized power, distributing tasks not decisionmaking. Nonetheless, significant nodes of local organizing developed that could have formed the seeds of far greater local organizing. The deep objection to the decision at the time (and now) is that it shut down powerful organizational power, and had nothing to do with an assessment good or bad of the effectiveness of the field program.”

Powerful organizational power, it seems, is not something dreamt of in Shor’s philosophy (or perhaps I should be more precise and say business model).* But he does read polls. So perhaps he should consider this little fact about OFA: After the 2008 victory, the Obama campaign polled its massive 13 million-member email list, and more than a half million people reportedly responded. Two-thirds said that not only were they interested in helping the President pass his legislative agenda, they believed it was important to elect state and local candidates to advance the goals of the campaign. And more than ten percent (50,000+) said they personally were interested in running for local office. When OFA was folded into the DNC, no significant resources were put into supporting local organizing. Those 50,000 potential candidates were left to fade back into the woodwork.** And over the next eight years, Democrats lost tremendous ground in statehouses—a net drop of 948 legislative seats according to Ballotpedia. Twenty-nine state legislative chambers in 19 states flipped from Democratic to Republican control over the course of Obama’s two terms. In ten states these flips resulted in the creation of Republican trifectas, where Republicans controlled both chambers as well as the governorship.

The fact that Patrick Gaspard now publicly regrets NOT pushing Obama to keep OFA going is 100 times more interesting than whatever David Shor thinks. The suggestion that Obama has an “evolving sense of how he managed or didn’t manage that movement coming into his presidency, and whether or not there were ways to deploy that energy that could have accrued to our benefit” is also intriguing (especially as he made zero mention whatsoever of his grassroots movement in his memoir A Promised Land).

But there’s a reason why Shor’s opinion still matters. That’s because there’s still a gigantic debate underway across the Democratic ecosystem about what went wrong in 2024. On one side are the people and institutions that basically think we just need a better candidate who is more in tune with public opinion and who avoids raising issues of concern to its activist base, and that we don’t have to change anything about how Democrats campaign or, more deeply, what the party and the whole constellation of groups and activists around it organize to do in the 21 months in every two-year cycle that aren’t right before an election. Just follow the polls and deploy the messages that test best in the lab, aka “popularism,” the position Shor upholds. As for trying anything like the massive field organizing operation constructed by the Obama campaign in 2008 or that Mamdani built in 2025, well, look at this one study from Wisconsin that supposedly shows it “likely cost the campaign votes,” as Shor tweeted.

Facts are Stubborn Things

There’s one little problem. That Wisconsin study is basically useless. “Unresponsive and Unpersuaded: the Unintended Consequences of Voter Persuasion Efforts,” by Michael Bailey, Daniel J. Hopkins, and Todd Rogers, says that when 56,000 registered voters in the state were picked by the Obama campaign in mid-October 2008 to be targeted for persuasive appeals by canvassers, phone-calls and/or mail, those contacts “reduced responsiveness to a follow-up survey among infrequent voters … [and] the persuasive appeals possibly reduced candidate support and certainly did not increase it.” Sounds bad, right? And indeed, sometimes unwanted voter contacts can backfire.

But this study can’t say if the reason it spotted a decline in candidate support is because the Obama volunteers’ efforts turned off voters. That’s because the researchers only know which voters were targeted for persuasive appeals – not who was actually touched. For example, in this study, 80% of the people assigned to the canvassing group never actually talked with a canvasser. Furthermore, the researchers have no idea of the quality of canvassing conversations with the 20% who did have a conversation with someone who knocked on their door. If they did find null effects or backlash from those 20%, they can’t say if it was because of good canvassing, bad canvassing, or something in between. (Same for the phone contacts, where only 14% of the targeted population was reached.) It’s a mush, and one that certainly doesn’t justify the sweeping conclusions made by Shor and Robinson.

Deep in the paper you can find its authors admitting that they’re skating on thin ice. They write:

“The organization did not report the outcome of individual-level voter contacts, meaning that our analyses must be intent-to-treat. Put differently, we do not observe what took place during the implementation of the experiment, and so are constrained to analyses which consider all subjects in a given treatment group as if they were treated. Subjects who were not home or did not answer the phone are included in our analyses, as are those who indicated strong support for a candidate and so did not hear the persuasive script in person or by phone.”

The rest of the study also suggests that it really shouldn’t be used for making sweeping statements about the value of field operations, though it might be useful for lining cat litter boxes. Its finding that after infrequent voters might have been contacted they were less likely to answer a follow-up survey call made in the final weeks of a hard-fought election doesn’t prove anything – other than the commonsense likelihood that as Election Day approaches, targeted voters get sick of unwanted political phone calls! Other problems with this paper include the fact that the entire study was focused on single-voter households only, excluding most married couples, families and roommates. Such singles are likely older, more isolated and potentially more suspicious of strangers at their door. The people targeted for persuasion in this study also weren’t the main focus of the Obama field operation—which sought to mobilize its base voters and new registrants far more than people still on the fence about their choice. And it’s crazy to make vast judgments about one voter contact operation in October in a swing state, when such people have already been bombarded from every angle.

If anything, there’s solid evidence that Obama’s 2008 investment in local field offices had a demonstrably positive effect on his county-level general election vote. Seth Masket of the University of Denver found that it “helped to boost his vote share by almost one point overall and by more than three points within some states.” His analysis suggests that “three states, worth fifty-three electoral votes, may have gone Obama’s way because of the effective allocation of field offices,” turning “a tossup into an Electoral College blowout.”

Towards a New Way of Seeing What Works

Dear reader, I wouldn’t have taken you this far into the weeds if it weren’t to make a larger point. For more than a decade if not two, the dominant paradigm for discussing “what works” in politics on the Democratic side has focused on “treatments” that supposedly tilt voting behavior in elections in significant enough ways to affect outcomes. Modest tweaks in tactics, like semi-personal postcards or text-based nudges or mailers that subtly shame voters by comparing them to their neighbors’ voting habits or scripts that require canvassers to ask a voter their specific plan for voting, get outlandish amounts of attention. Meanwhile no one really checks to see if they’re implemented well or worries when the humans attempting to use these tactics in the field report pushback. The data model says “they work,” after all. Someone did a random controlled test!

(And the whole secondary economy of influence, where a big donor can write a big check for a voter registration or GOTV effort that some “cost per vote” study showed X effort would produce Y votes, means that said donor can go talk to the person they’re really targeting – a US Senator or Governor, say – and claim that their money helped them win Z election, so now you owe me favors.)

Fortunately, a different approach to organizing people to win power is well on its way to challenging this paradigm. You can find it in things like Civic Power: The Role and Impact of Independent Political Organizations in Expanding the Electorate and Building Governing Influence, a recent report by Joy Cushman, research director of the Democracy and Power Innovation Fund, and Elizabeth McKenna, an assistant professor of public policy at the Harvard Kennedy School and faculty director of the Civic Power Lab. You’ll also find it in Swing Left’s new “Ground Truth” project, which seeks to change how Democratic activists engage with voters by getting them to listen first before trying to persuade. This work has important implications not only for how we engage in election campaigns but also in how we organize for meaningful policy wins and to combat authoritarianism.**** In future issues of The Connector, I plan to dig deeper into the new way of seeing that researchers like Cushman and McKenna are pioneering, as well as the actual practice of power-building groups that are applying these concepts on the ground in many states. Stay tuned!

*The Senate Majority PAC has paid Blue Rose nearly $3 million since 2024. The Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee is also a major client.

**Today we cheer groups like Run For Something, which has attracted the engagement of more than 250,000 people interested in running for office over the last eight years. Imagine what a different world we might be living in had the 50,000 galvanized by Obama in 2008 hadn’t been abandoned.

***I’ve never met David Shor so this headline is not a comment on him physically.

****To give one very current example: A coalition of power-building groups just succeeded in gathering 300,000 signatures in Missouri seeking to put a referendum on the ballot next year to block that Republican-dominated state from re-gerrymandering its congressional districts mid-decade.

Clearly, we need to be taken into these weeds! Up until now I was blissfully unaware that some people - some powerful people - argue that destroying OFA was a good idea. Good grief. I thought it was just that folks didn’t know about it, and didn’t understand how it led to us not competing in and thus losing so very many states. As for your question about why he and his ilk are powerful, is his daddy rich? Was he college roommates with a senator’s son? Did he date a Cuomo or a Kennedy? I’m sorry. I know that’s obnoxious. But seriously. Why????

Thank you for writing this.