Welcome to the Silly Season

With 2024 looking like a Biden-Trump rematch, now's the time to let your imagination run wild about third-party plays like a Dwayne Johnson/Mark Cuban ticket--and then get sober about hard realities.

Not long ago, I got a query from my friend David Callahan, the publisher of InsidePhilanthropy.com and BlueTent.us. He wrote, “As a former Perot expert, here's a question for you: If a similarly strong -- or stronger -- third-party candidate runs in 2024, and has plenty of money and ballot access in all 50, what vote share would you predict for them?

My answer surprised him: “As strong or stronger than Perot is a tall order, but such a candidate could win if the D-R matchup is a re-do of 2020.” I noted that David didn’t include access to nationally televised presidential debates, but since Perot was included in those, I assumed the same. And I also noted that one of David’s conditions, ballot access in all 50 states, wasn’t very likely. Perot managed to do it, but several big states, most notably Texas, make it quite hard to pull off.

David wrote back that he thought the increased level of polarization in the country would make it hard for any hypothetical independent to even come close to the 19% that Ross Perot garnered in 1992. And he could be right. On the other hand, I think the “exhausted middle”—people who are not hardcore political warriors and who just want things to work and all of us to get along—is up for grabs. So if 2024 is a replay of Biden-Trump and if, and only if, we get a credible non-politician ticket that is on all 50 ballots and has funding like Perot did, such a candidacy could blow a huge hole between the two major parties the way that independent Jesse Ventura shocked the political establishment in the Minnesota governor’s race 25 years ago.

Am I crazy? Consider the following.

Few people remember this, but in the late spring of 1992 President George H.W. Bush and Governor Bill Clinton were losing to Perot in the polls. A Washington Post-ABC News poll in early June 1992 found that among likely voters, Perot was preferred by 38%, to 30% for Bush and 26% for Clinton. The billionaire businessman had only announced his willingness to run four months earlier, in an appearance on CNN’s Larry King Show, but he had rocketed to the front of the field by dispensing folksy wisdom on TV, taking few questions from reporters, and letting his grassroots supporters do all the heavy-lifting of getting him on the ballot.

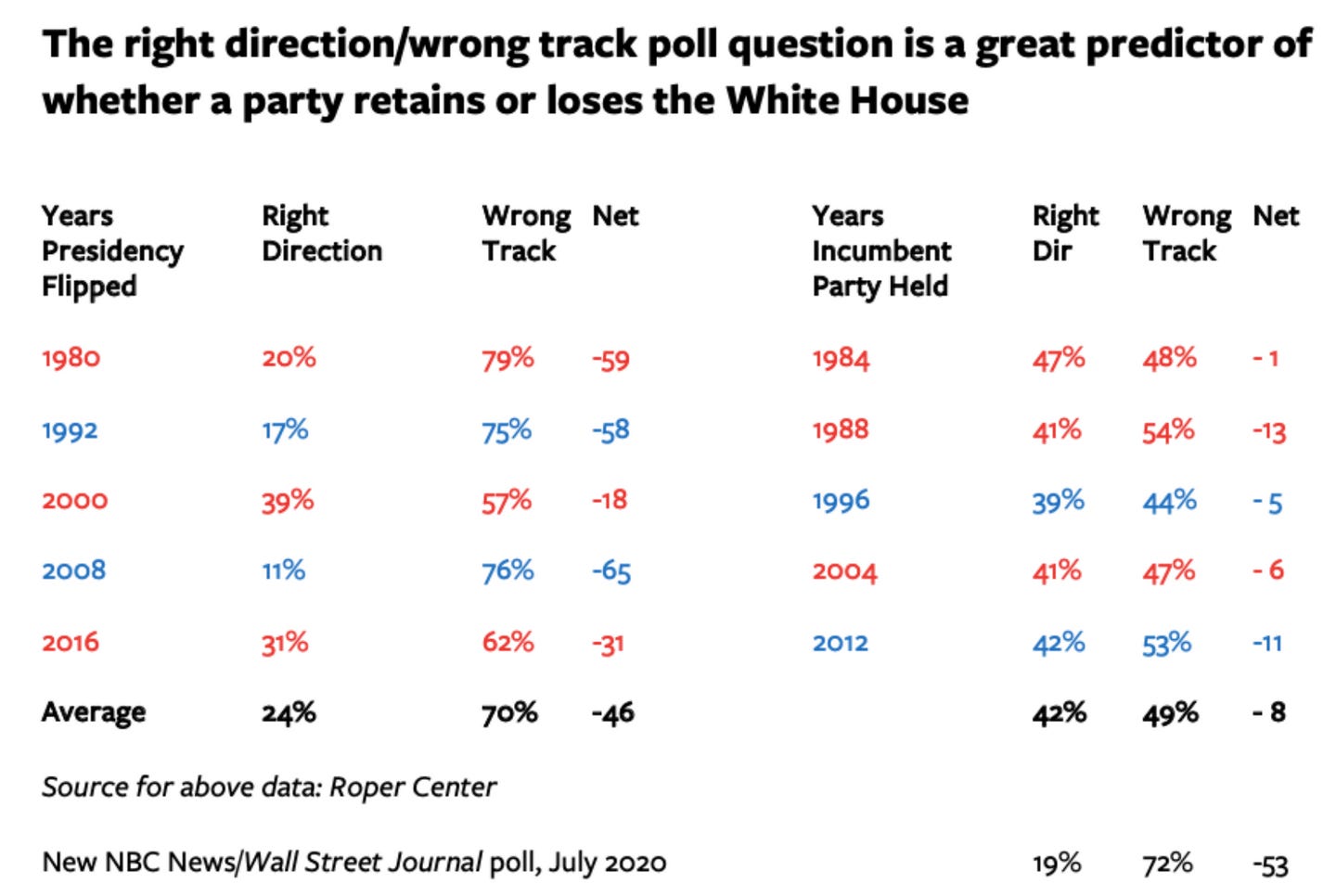

Why was Perot doing so well? Well, people were feeling pretty unhappy about the direction of the country at the time. As Charlie Cook pointed out not long ago, when substantially more Americans think the country is on the wrong track than the right one, the incumbent party in the White House loses. Perot picked an especially good cycle to toss his hat into the ring.

Of course, Perot didn’t win that election. June 1992 was the high watermark of Perot-mania in America. He soon experienced a barrage of negative publicity (much of it deserved) and cracked up, making up a paranoid story about threats to his family and suspending his campaign. But in the fall, he changed his mind and got back into the race, using the debates and millions of his own money on a series of 30-minute (not 30-second) TV ads that made a coherent case for his candidacy. The result: he got 19% of the vote overall.

What this shows is the soft underbelly of our two-party duopoly. As long as there are just two major candidates on the ballot, voters will gravitate toward them, either because they genuinely like one of the candidates or, as it frequently the case, because they really dislike the other one more. But if someone manages to overcome the obstacles to getting on the ballot and, crucially, gains the legitimacy that comes from being included in the presidential debates, we’re in a different game. Such a candidate still has to convince voters they can win, because in the waning days of a hard-fought election both major parties and nearly all the media will be saying that they can’t. Exit polls from 1992 show that this was the final blow to Perot’s chances—when asked if they would have voted for Perot if they thought he could win, 36% said yes, almost double his actual showing.

The new New York Times/Siena poll shows that Americans are pretty unhappy about the direction of the country, with 65% saying it’s on the wrong track vs 23% thinking the opposite. (Look again at the above chart.) And despite holding the White House, Democratic support for the incumbent is soft. Negative partisanship—the dislike of the other party’s standard-bearer—is the main thing buttressing Biden. Fifty percent of likely Democratic primary voters say they want their party to nominate someone else. If that isn’t a like a bad cholesterol report on your blood test, I don’t know what is. The heart of the Democratic party is weak.

Imagine Dwayne Johnson (“the Rock”) as the standard bearer of a “Common Sense” party, with someone like Shark Tank’s Mark Cuban as his running mate. They have all the name recognition they need. They could self-finance. Their appeal to working-class voters would be obvious (Johnson’s a big backer of the SAG-AFTRA union; Cuban is saving consumers lots of money with his CostPlus Drug online retail site.) That would be a very potent combination. Would it happen? Very unlikely (as both Johnson and Cuban, who have each dallied with running for president, endorsed Biden in 2020). So even speculating this way is why we call August the “silly season” for political punditry.

There’s a serious point to this exercise, though, which is aimed at all the people currently worrying—with good reason—that the self-styled centrist group No Labels is going to blow up the 2024 rematch between Biden and Trump by nominating an independent ticket made up of West Virginia Senator Joe Manchin and former Utah Governor Jon Huntsman Jr. That bipartisan pairing would appeal to very few people, but likely just enough to tip the election to Trump.

Right now, there’s a wild-bedfellow coalition of Never Trumpers, centrist groups like Third Way, and progressive outfits like MoveOn doing everything they can to block No Labels, filing lawsuits and asking secretaries of state to investigate their ballot access efforts.

Of course, politics isn’t beanball, and those kinds of brass-knuckled tactics may well hobble the No Labels bid. But the malaise afflicting Democrats is serious. The sharp (48%) drop in donations from small political donors in the first half of 2023 is just another indicator of the problem. In some other universe the money that is now being spent to stymie No Labels could be much more productively spent rebuilding the state and local infrastructure of the Democratic party. After all, Band-Aids don’t cure heart disease, they just hide it.

—Related: Don’t miss Lee Drutman’s wise analysis of the latest New York Times/Siena poll. He’s right that there’s a lot more possibility under the surface of our calcified and gridlocked two-party system, and one way or another it’s going to get tapped.

Deep Thoughts

—Dave Karpf has some second thoughts about his 2013 book The MoveOn Effect, which I highly recommend. The key question is why the Big Email groups that he heralded in his book never chose to support what he calls “neo-federated” membership models supporting lots of local chapters, and I think he gets at nearly all the answers. But in addition to the high costs of building and maintaining federated membership groups with healthy internal cultures, his main reason, I’d add one more: the Big Email model gives a few people a lot of control over how their group (MoveOn, Color of Change, UltraViolet, et al) will act in the world. Empowering members in chapters inherently means sharing decision-making—i.e., losing that control.

—Anne Applebaum’s report in The Atlantic on the decline of democracy in the state of Tennessee is probably the most depressing thing I’ve read lately about what is happening to the Republican party. Here’s just a short excerpt: “Walking to her home in Nashville, an acquaintance saw a car with a shoot your local pedophile bumper sticker, showing an outline of a man holding a gun to another man’s head. T-shirts with this image, phrasing, and implied approval of violence are for sale online. ‘This isn’t new to you, but it’s new to us,’ she told me, which isn’t quite true. Poland, where I live part of the time, has had one political murder in recent years, but it was a knife murder. In Tennessee, people have guns. Jim Cooper, the former member of Congress, told me that getting anyone to run for office as a Democrat in some rural parts of the state is difficult partly because Democrat and pedophile are so often conflated by Republican activists, and potential candidates are spooked. About half of the state-legislature seats were uncontested in 2022.”

Odds and Ends

—If you haven’t seen Oppenheimer yet, go while it’s in the theaters (though be ready for some of the soundtrack to needlessly drown out the dialogue at a few moments). It’s the best political movie I’ve seen in a long time, not only for how it revives our awareness of the nuclear danger but also for showing the importance of dissent and freedom of speech when faced with existential questions of war and peace.

It's only after seeing the movie, though, that you can truly appreciate the chutzpah of Alexander Karp, the CEO of Palantir Technologies, who was given the entire back page of the Sunday New York Times to expound on why the US—led by defense contractors like his company, which sells data analysis tools to the Pentagon—should rush to develop AI-powered weapons. Astonishingly, and without any sense of irony, Karp compares the development of bigger and bigger nuclear weapons—the largest being the 50,000-kiloton Tsar Bomba, which was powerful enough to cause third-degree burns 100 kilometers away—to the development of large language models. But the crowning hubris of Karp’s essay is his claim that we have to develop AI weapons so that “we,” the United States, will maintain our hard power superiority over other countries. As if this is even a “weapon” that “we” will be able to control. Karp also says, regarding the many AI experts and engineers who have called for caution in the further development of LLMs, “The preoccupations and political instincts of coastal elites may be essential to maintaining their sense of self and cultural superiority but do little to advance the interests of our republic.” Good lord.

—My friend Hollie Russon Gilman has a smart roundup of all the ways that investing in civic infrastructure can help address America’s “loneliness epidemic.”

—Participate: Dizzy Zaba, a Ford Foundation technology fellow, is working on a research project about the state of online-to-offline organizing in the progressive movement ecosystem and is asking folks who are organizers, campaigners or strategists to take this short survey.

End Times

RIP, Paul Reubens. Remember it was the height of the Reagan years when he managed to do this.

Thanks for the David Karpf link, Micah. So timely. So sobering.

I always have a question about the "right direction/wrong track" question: How are people who believe that the incumbent party is "not going far enough" counted in the results? For example, if someone thinks that Biden should never have given in on oil leases in the Arctic and that we should be making faster progress on decarbonization, stopping all fossil fuel incentives, taxing the rich more, opposing threats and limits on reproductive choice, and supporting immigration, while neither the White House nor the Republicans in DC or on the Southern border are doing the right thing with regard to these issues, would that person answer that we are on the "wrong track"?

The same "wrong track" answer of someone who thinks that Biden is a criminal, that Democrats are destroying the fabric of the country, that Trump is the savior?