When Hurt People Hurt People

The paradox of being powerful and feeling powerless; how the Israel-Hamas war is polarizing Americans; and the possibility of a different path.

Two weeks ago, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict bubbled over in my little village. After the October 7 attack by Hamas, most of the neighboring towns and jurisdictions had issued statements on the massacre, emphasizing their solidarity with Israel and Jews. But our mayor (who, to be clear, is paid something like $4,000 a year) hadn’t rushed out a statement like the others, and after several days some people started to get upset “at the silence.” Finally, on October 17, ten days after, she posted and emailed “A Message of Love and Solidarity.”

It begins, “I want to acknowledge and thank all of you who have shared what you’ve been feeling these last ten days, especially our Jewish and Muslim residents. The news of the devastating terrorist attack on innocent Israelis by Hamas horrified all of us, and the humanitarian crisis in Gaza breaks our hearts.” And it goes on to recognize, with clear empathy, how deeply personal and profoundly terrorizing it is for many, especially those who “have family and friends whose homes have been destroyed, […] know people who were wounded, killed or held hostage, they are traumatized and in mourning.”

That night, at the regular meeting of the town’s board of trustees, three local women, all Jewish, read from an open letter on behalf of about two dozen residents, lashing out at the mayor for how long it took for her to issue her statement, and accusing her of “all-lives-mattering” the topic when what they wanted to hear was “Jewish lives matter.” Most startling and poignant, they said they did not “feel safe” in our little town because of this, and one even said she thought she’d be safer going back to Israel where she is from.

I live in Westchester County, NY, one of the most affluent and safe places in America. The crime rate in the town of Greenburgh, which includes my village, is among the lowest in the state, 51 serious crimes per 10,000 population in 2020. Overall crime across the county has dropped significantly between 2017 and 2022.

Beyond that, American Jewry has achieved a remarkable level of prosperity, security and power considering that we are just two percent of the population. Support for Israel, even blank checks for Israel, is the default position for almost all of Congress. Is there any other contentious issue where Republicans and Democrats compete to outdo each other the way they posture at being pro-Israel?

But I am not going to deny someone’s lived experience: Jews in Westchester are saying they feel unsafe. And they’re not the only ones. What is going on? Yes, antisemitic incidents are up (though the ADL, which is the business of tracking these, has a disturbing way of conflating political speech with being antisemitic or “pro-Hamas.”) So are attacks on Muslims. People who “appear” to be Jewish or Muslim, or their buildings or offices, have been targeted for attack. Jewish students in college are having to deal with a lot of discomfort. But to feel “unsafe” in my precious little village?

Lately I’ve found myself thinking a lot about the problem of intergenerational trauma, and what trauma does to our ability to empathize with others. I think it’s fair to say that every Jewish person, except perhaps those who have converted from some other identity, carry with them some inherited trauma from how their parents, grandparents or other ancestors were harmed by antisemitism, as well as trauma from their own experiences. In addition we have collective trauma, from a shared history of oppression and persecution. And from that we have evolved a group of behavior patterns, which Kohenet Jo Kent Katz calls “embodied acts of survival and resistance to legacies of oppression.”

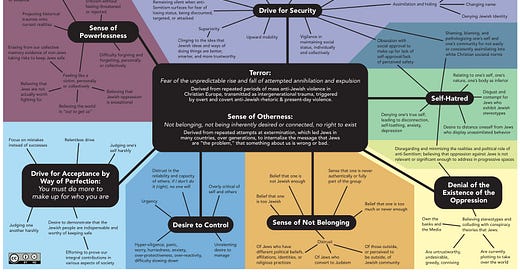

Take a look at this map, which was created by Katz as part of her Transcending Jewish Trauma website. Everyone of these behavior patterns are manifestly present in how Jews, especially Ashkenazi Jews who are the descendants of people who lived in Europe, navigate the world: starting with an overarching sense of encroaching terror and a feeling of being othered, we have the drive for security, the sense of powerlessness, the drive for acceptance by way of perfection, the desire to control, the sense of not belonging, the denial of the existence of the oppression, the self-hatred. Today, in the wake of October 7, several of these patterns are in overdrive, especially the paradox of seeking security from amassing state power while feeling an overwhelming despair at ever being secure.

It’s not for nothing that nine years ago, comedian Jon Stewart perfectly captured how sensitive Jews are when the topic of criticizing Israel arises. We have tremendous inherited trauma that has not been processed; and instead of working on healing most of our political and communal leaders insist on reinforcing these collective behaviors at every turn. The Israeli sociologist Eva Illouz makes this point exceedingly clear in her new book The Emotional Life of Populism. For decades, Israeli leaders have used past trauma to legitimize an overly warlike response to adversity. In April 1956, an Israeli kibbutznik Roi Rotberg, was kidnapped and killed by fedayeen (guerillas) from Gaza during a series of skirmishes along the border. Moshe Dayan, then a general, later to command Israel to victory in the 1967 Six Day War, eulogized him thus, in a speech considered to be one of the most influential in Israeli history:

“It's not among the Arabs in Gaza but in our own midst that we must seek Roi's blood. How did we shut our eyes to the reality of our fate, unwilling to see the destiny of our generation in its full cruelty? Have we forgotten that this small group of young boys, settled in Nahal Oz, is carrying the heavy gates of Gaza on its shoulders? Beyond this, hundreds of thousands of eyes and arms huddle together and pray for our coming weakness, so that they may tear us to pieces. Have we forgotten this? Don't we know that in order for the hope of our destruction to perish we must be armed and ready, morning and night? We are a generation of settlement, and without the steel helmet and the cannon's maw we cannot plant and build a home. Our children won't have lives to live if we won't dig shelters. And without a barbed wire fence and a machine gun, we won't be able to pave a path or drill for water. The millions of Jews who were exterminated and have no land are watching us from the ashes of Israeli history and command us to settle and rebuild a land for our people…. We will make our reckoning with ourselves today. Let us not flinch from the hatred that accompanies and fills the lives of hundreds of thousands of Arabs, who are sitting and longing for the moment their hands can get our blood. We must not avert our gaze, lest our hands be weakened. That is our generation's fate and our life's choice -- to be willing and armed, strong and unyielding, lest the sword be knocked from our fist and our lives cut down.”

As Illhouz writes, “Dayan’s speech is exemplary of what would become the essential blueprint of the Israel psyche. Dayan puts here annihilated Jews throughout the world and throughout history at the center of Israel consciousness. It is to them the nation now addresses itself and it this group that the nation represents. Arabs become an undifferentiated mass, full of hatred, mirroring the ancestral threat of annihilation. A small group of fedayeen became a vast threatening entity.”

In 1967, Yitzhak Rabin, who was then the army chief of staff, explained Israel’s smashing success in that war by saying that its soldiers fought so well because they understood “that if victory was not theirs the alternative was annihilation.” And in 1982, when Israeli invaded Lebanon in an ill-fated attempt to destroy the Palestine Liberation Organization, which was then based in Beirut, then-Prime Minister Menachem Begin said, “The alternative is Treblinka, and we have decided that there will not be another Treblinka.”

Benjamin Netanyahu has both continued to weaponize Jewish trauma as well as extend its use. In 2000, he wrote that the concept of Palestinian self-determination comes directly from the Nazis, Illouz notes. In 2002, he backed the US invasion of Iraq because “we now know that had democracies taken preemptive action to bring down Hitler in the 1930s, the worst horrors in history could have been avoided.” In 2006, he asserted that “It’s 1938 and Iran is Germany.” And in 2010, he promised that “we won’t forget to be prepared for the new Amalek, who is making an appearance on the stage of history and once again threatening to destroy the Jews.” Last week, he told German Chancellor Olaf Scholz “Hamas are the new Nazis.”

It's in this context that we have to understand Netanyahu’s statement last Thursday, as he announced Israel’s plan to expand its war in Gaza. Describing his meetings with some of the front-line soldiers as they prepared to invade, he said, “They are longing to recompense the murderers for the horrific acts they perpetrated on our children, our women, our parents and our friends. They are committed to eradicating this evil from the world, for our existence, and I add, for the good of all humanity. The entire people, and the leadership of the people, embrace them and believe in them. 'Remember what Amalek did to you' [Deuteronomy 25:17]. We remember and we fight.”

Amalek was a tribe based in the western Negev desert (talk about history rhyming) that attacked the Hebrews by surprise on their march out of Egypt, killing the weak and old who were straggling at the rear. Afterwards, the Torah says that God told Moses to record and never forget the story of Amalek’s treacherous assault, but also promised to wipe the memory of the tribe from the earth. It’s a paradoxical charge—remember to obliterate the name of Amalek for all time. For some Jews, the ancestors of Amalek are everywhere that the Hebrews encounter oppressors, like the Book of Esther, which traces Haman—another villain who seeks to exterminate all Jews—back to Amalek. (Here’s a Long Island rabbi invoking Amalek to justify the complete destruction of Gaza and dispersal of its residents to other lands.) In a different, perhaps lesser, Jewish tradition, Amalek is just an ancient people that has long since disappeared. No Amalek, no problem. No Nazis, no problem.

The problem though, is how much we Jews, both abroad and Israel, have failed to metabolize the trauma of the Holocaust, which itself sits atop these older memories. (And inside the American progressive movement, Jews have been expected to deemphasize their concerns about antisemitism in service of a larger shared racial justice agenda, which hasn’t helped.) Thanks to survivors like Elie Wiesel, the Holocaust is taught as something so evil that it can’t be analyzed or comprehended, not as the extreme manifestation of Western imperialism, colonialism and racism. As Naomi Klein writes in Doppleganger, “the facts of the Nazi genocide were drummed into us like arithmetic tables: the numbers of dead, the twisted forms of torture, the gas chambers, the cruelly closed borders….I am struck by what wasn’t a part of these strangely mechanical retellings. There was space for the surface-level emotions: horror at the atrocities, rage at the Nazis, a desire for revenge. But not for the more complex and troubling emotions of shame or guilt, or for reflection on what duties the survivors of genocide may have to oppose genocidal logics in all their forms. I am struck that we never actually grieved, nor were we invited to seize our anger and turn it into an instrument for solidarity. As Cecilie Surasky, one of the founders of the anti-Zionist group Jewish Voice for Peace, said to Klein, “It’s re-traumatization, not remembering. There’s a difference.”

But what happens when traumas resurface?

A friend recently shared a link to an old episode of the podcast Hidden Brain, titled “What Happens When You Empathize With the Enemy.” It focuses in part on Breaking the Silence, an organization of Israeli military veterans who are striving to educate their fellow citizens and the rest of us about the harsh and dehumanizing realities of the occupation. One of the responses to their work, from other Israelis, is to accuse them of being traitors. Why? Because seeing people from your own “tribe” show sympathy for the other makes people in your tribe angry. A study by psychologist Lee Ross at Stanford, the podcast notes, found that when shown news clips about the conflict, pro-Israeli students report seeing lots of anti-Israel references and pro-Arab students report seeing more anti-Arab content. Each wants validation of its side and reacts viscerally to those offering another side.

But even worse, when you remind people of the suffering of their own group, they become less empathetic toward other groups. From the podcast: “The psychologists Michael Wohl and Nyla Branscombe once asked Jewish volunteers to think about the suffering of Palestinians. The psychologists reminded some of the volunteers about the Holocaust. Compared to others, Jews reminded of their own group suffering showed less compassion toward Palestinian suffering. The same thing happens with other groups. Americans reminded of traumas, even distant traumas like the Pearl Harbor attack, show less empathy for victims of torture carried out by American service members. Trauma makes us turn inward. It creates justifications for the harm we cause other groups. It makes it harder to feel empathy for our enemies.”

What can change this dynamic?

One answer is realizing that instead of the two sides being Israelis vs Palestinians, to think in terms of Israelis and Palestinians who are for peace and those who are against it. This is not where we are now. Instead, we here in the Jewish and Palestinian diaspora are now being polarized and enrolled in a shadow version of the actual war playing out along the Mediterranean. The declarations being made and demanded almost all add more gasoline to the fire, with a few rare exceptions like this tempered and sane joint statement from the leaders of the Muslim and Jewish law student groups at the University of Ottawa. On the “pro-Israel” side, Jewish communal organizations like the Boston Jewish Community Relations Council are kicking out venerable organizations like the Boston Workmen’s Circle for daring to dissent against the continuation of Israel’s war in Gaza, while continuing to embrace far-right groups like the Zionist Organization of AmerIca.

And on the “pro-Palestine” side, activists are doubling down on their own polarizing choice. For example, Tuesday night, along with 2,000 other people, I attended an online teach-in/webinar on the conflict put on by Rising Majority, a coalition of multi-racial groups on the left that grew out of the Movement for Black Lives. After some opening songs and solemn remarks about the war’s victims in Gaza, a speaker offered their history of the Zionist project in Palestine. She showed us Theodore Herzl, the founder of Zionism, and shared the various conflicting promises made to the Jews and Arabs by their British overlords in the early 1900s. Suddenly she was on 1947-48. I had to rub my eyes in disbelief. There was no mention of the Nazis or the Holocaust, let alone the fact that Jews have their own indigenous ties to Palestine along with Arab Palestinians. I signed off soon after. (You can watch for yourself here, at about 35:00-36:00 in)

I’m particularly worried right now that many of our city streets are being converted into loci for conflict, as people seeking to draw attention to the plights of the hostages held by Hamas paper walls with photos of the missing—some of them placed provocatively close to Palestinian or Arab businesses—and now people angered by the deaths of Gazan civilians are starting to respond with their own posters of Palestinians killed by Israeli bombs. This will not lead anywhere good, unless someone figures out a meta-meme that encompasses both causes and neutralizes them.

It's understandable why people from both camps who are directly affected, Jews and Palestinians, would be retreating into their tribal corners. The fact that so many Jews have made the deliberate effort to empathize with the others by showing up at rallies in Washington and New York City to demand a cease-fire to stop the killing is not an act of personal self-hatred but of communal self-healing, all the more astounding because of the cross-ethnic solidarity it embodies. That is not something you see large numbers of any other ethnic group doing in the midst of mortal combat. Some of us are indeed trying to see past our collective trauma.

But what I still do not understand is why anyone on the left would choose to accelerate this polarization by adopting the black-and-white narrative that condemns all Israeli Jews as settler-colonialists, rather than buttress the efforts of Israelis and Palestinians committed to the path of co-existence. As Simon Sebag Montefiore writes (gift link) in The Atlantic, the decolonization narrative is dangerous and false, a mirror image of the narrative of the Israeli settler movement with its dangerous fantasy of removing all the Palestinians from the “Greater Land of Israel.”

There are alternatives:

Read “My lonely search for a Jewish community that lives its values,” by my friend Erin Mazursky in Waging Nonviolence.

Read “3 key insights for building a powerful and loving movement against oppression in Palestine-Israel,” by Rae Abileah and Nadine Bloch of Beautiful Trouble, also in Waging Nonviolence.

Read “When Both Silence and Statement Become Complicity,” by Charlotte Clymer on Substack.

Read Harold Meyerson, “Israel, Palestine and the Generational Rift Among American Progressives,” which makes a solid case for a strategic cease-fire inside the progressive movement.

Read “We’re Seeing the Calamitous Cost of Ignoring Palestine,” by Yousef Munayyer in The New Republic.

Read “Beyond the Carnage: Credo of a democratic Zionist,” by Sam Schube, a member of Kibbutz Nir Am and chair of Hagar, Jewish Arab Education for Equality.

Read “‘A kind of tribalism’: US supporters of Israel and Palestine fail to admit suffering of other side,” by Chris McGreal for The Guardian.

Read “Vengeful Pathologies,” Adam Shatz’s brilliant essay in the London Review of Books on the war in Gaza.

Read “Amid Israel-Hamas War, Some Still See a Path to Coexistence,” by Marc Champion in the Washington Post, which features profiles of Israeli Jews and Palestinians working at the intersection of their worlds.

See the “Two States, One Homeland” initiative of A Land for All.

End Times

This is for everyone who has done the reading.

Thank you for writing this, it's so important

Really appreciated this piece, thank you for writing it