When the Doors You Knock Belong to Your Own Neighbors

Face-to-face canvassing is a potent tool; why don't we do it locally year-round? Plus some gleanings from Netroots Nation 2022.

New York, my home state, is having its second primary election today thanks to a court ruling that threw out the redistricting maps drawn by our Democratic-controlled legislature and required the drawing of new lines for Congressional and state senate districts. As a result, I’ve had the opportunity to do something that I’ve always been interested in doing and never had a good excuse to do: I’ve canvassed my own neighborhood. And the experience was kind of mind-blowing.

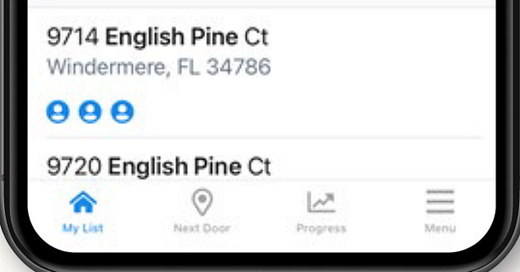

I’m assuming that most readers of The Connector know what canvassing is, but just in case here’s a quick refresher. On the Democratic side at least, it involves giving a volunteer a list of names and addresses to door knock and talk to, typically following a script recommended by the candidate’s campaign. These days, those lists are generated from the state party’s voter file, culled by the candidate campaign to whatever universe of potential voters they are focusing on, displayed on a mobile app called MiniVAN. (VAN stands for “voter activation network.”) In the primordial days of carbon-based politics, we used sheets of paper and clipboards to keep track; now MiniVAN displays all the info a volunteer needs. The tool drastically streamlines the work of managing a field campaign because lists are generated and updated digitally, relieving field staff of hours they used to have to spend nightly transferring hand-collected data to campaign spreadsheets.

I can’t remember the first time I canvassed for a candidate but it was probably in the late 1990s, when I spent an evening walking a neighborhood in Pelham, a suburban town in Westchester, not far from where I live, where the Working Families Party was involved in a battle for town board. I’ve canvassed in crowded Black and brown neighborhoods in North Philadelphia where you could hit 50 doors in just two blocks, depressed working-class towns along the Delaware River where every other home was a converted trailer, Hispanic suburban neighborhoods in Aurora, Colorado; exurban sprawl in upstate New York wine country where houses sit acres apart and it took half a day just to cover one turf, and various bits of more local turf on the leafy streets of the northwest Bronx and lower Westchester. Most of these were traditional canvasses focused on quickly identifying whether a voter was a strong supporter of my candidate or to encourage previously identified supporters to go vote, but in 2020 I also got trained in deep canvassing by the good folks at Changing the Conversation Together. At the doors I knocked with them in and around Philly I engaged in longer, more searching conversations with potential voters hoping to make an empathetic connection and remind them why they themselves wanted to vote, which I wrote about for the American Prospect.

According to lots of field research, a strong door-to-door canvassing operation can significantly improve voter turnout, potentially gaining a candidate a couple of points. Which matters a lot in close races (and also probably hurt Biden in the 2020 general election since Democrats were far more hypervigilant about Covid than Republicans). But in many places voters are rarely canvassed because their incumbents hold safe seats. So, if you are a motivated volunteer who wants to help your party, it’s far more likely for you to canvass districts far from home. Research has shown that the interactions that result may not be as persuasive in part because the kinds of people who volunteer are typically older, better educated and/or whiter than the infrequent voters they are sent to talk to, and can even turn those voters off if overdone. However, one side benefit of this kind of canvassing is it may change the minds of the people who volunteer and make them more aware of the complexities of voter thinking. Unfortunately, most of this kind of voter contacting has been turned by the Beltway Brain into isolated gig work; it’s extremely unusual for someone who volunteers to canvass to make friends as part of the process, sometime I wrote about for the New Republic as “The Loneliness of the Resistance Protester.”

I digress. Here’s what happened when I got to canvass the very streets where I have lived for more than 20 years, in the mostly liberal Democratic town on Hastings-on-Hudson, NY, on behalf of my congressman and friend Jamaal Bowman: I discovered layers of potential grassroots power that I had no idea existed.

Just walking the hilly streets of my own neighborhood, in that rough half-mile radius I encountered: a young interracial couple who recently moved in who were so politically active they had been out canvassing for Bowman too; another new family where the (white) father greeted me at the door wearing the most profane anti-racist T-shirt I’ve ever seen; a peer whose kids had been friends with ours during high school that I had lost touch with whose wife was out volunteering for Bowman; two homes where residents told me they had donated to him; and two where people mentioned they had been writing postcards to voters elsewhere. Most astonishing to me, down at the far end of the turf I was assigned I saw a familiar name on MiniVAN and got to reconnect with a writer who I had interacted with years ago as an editor at The Nation. He’s now a very well-respected novelist and a member of the editorial board of a different progressive magazine; I think he was as amazed as me. He’s been living in my town for the last ten years; I had no idea.

I also got to connect with several other new neighbors, strengthen some relatively new friendships, and reconnect with a few people I hadn’t talked much with since my dog died and I stopped needing to walk her around the block every day. At almost every door, saying that I lived nearby, “just over the hill on ______,” helped warm up the encounter. Of the 96 addresses I was assigned, about half were home; I counted 70 votes for Bowman and maybe four for one of his two opponents. One person who was on the fence told me he was a long-time local Democratic party activist who worried that Bowman was too far to the left for his taste; one older Irish woman who said she always voted Democrat had clearly been watching too much Fox News; and one younger Jewish man snarled that he believed Bowman was antisemitic and slammed his door on me.

I now have a hand-drawn map of all these contacts. And when I walk in my neighborhood, which I do often for exercise or to just unwind, I’ll be looking to reinforce the connections I just made. I can easily see inviting the folks who are already more politically active into an organizing circle of some kind, like the Indivisible group I already belong to and help steer, or something a little less formal like a small donor group.

Now, imagine if more organizers-in-place had access to the Democratic voter file and a tool like MiniVAN that let them keep track of their relationships with people they live near. My town has a fairly active local Democratic party, but my district committee reps only come by when it’s time for them to collect petitions to get candidates on the ballot. I’ve lived here more than twenty years and have never been asked by them to do anything hyperlocal that would connect me to likeminded neighbors.

Why don’t local independent organizers do this on their own, you might ask? Well, access to the Democratic voter file isn’t cheap. It cost $8,500 for the Bowman campaign to get it from the New York State Democratic Committee. NGP VAN (which is now owned by a private hedge fund) charges about $5,000 a month for its ongoing services. And the data that canvassers collect as they knock on doors doesn’t stay with them; it flows through MiniVAN back into the state voter file.

There’s nothing preventing a state party from tapping local organizers to do this kind of data-enabled hyper-local network weaving, except a lack of imagination and a decided preference for the status quo. (One study by Betsy Sinclair and colleagues found that when canvassers were assigned to their own neighborhoods by a community outreach group seeking to increase voter turnout, voters who communicated with local canvassers were between 4 and 11 percent more likely to vote.) To be sure, if a party were to do that it would need ways to filter who it offers the data to, and you might get an oversupply of organizing in places that are already well-off and well-connected. Though that doesn’t have to be a bad thing if the result is that we strengthen people’s engagement and work to steer their available resources towards the places that need more organizing help or money.

What do you think? Is anyone already doing this in your corner of the country? Leave a comment and let’s talk.

Notes From Netroots Nation 2022

I didn’t attend Netroots Nation in person this year but did catch a few of the sessions online. One that caught my attention was this post-mortem on what went wrong in Virginia in 2021, where former Governor Terry McAuliffe failed spectacularly in his race against Republican Glenn Youngkin. The panel pulled no punches, covering how national funders misread the state as having gone solid Blue and failed to prioritize it, how McAuliffe lost the support of parents across the spectrum with out-of-touch comments that showed he had no feel for their stresses or anxieties, how his campaign failed to engage with core Democrats in Black communities taking their votes for granted, all the way down to a Saturday rally with Barack Obama a few weeks before the election where dozens of canvassers were pulled off prime shifts in order to help build the crowd of people “who had already voted.” It was all very illuminating and healthy to air. But at the very end, one thing that state senator Jennifer McClellan, who had also sought the governorship but lost to McAuliffe in the primary, really stood out to me. It’s worth quoting her remarks in full:

“We've been here before, right? Not that long ago, in 2009, when we lost the top three [seats statewide]. Part of it the party infrastructure should be you've got your local committee, year-round, doing sort of the organizing and touching the voters and then you have your constituency group organizations or women's caucus, your whatever caucus, doing the relational organizing year-round, so that that infrastructure is already in place, and when the candidates come along, you put the candidates in [to that]. The Virginia Democratic Party, by the way, after we lost in 1993, did a strategic planning process where we said that's what we're going to do. And that sat on a shelf. And then we pulled it off the shelf after we lost in 1997. And said, oh yeah, let's update this. We created an outreach plan. I wrote it. We created an outreach plan that basically said, we're gonna use all of our constituency group organizations that do relational organizing year-round. We did it for a little while, put it on the shelf. So I think part of the reason we did that is because we as a party became too dependent on wealthy candidates at the top of the ticket. If we're being honest, he wasn't as wealthy [as] that but like, if we're being honest, Obama kind of did this a little bit where they said, I don't want this party apparatus over here. I want Obama for America. I want to be in charge and have my people in charge not this party, right? So here, so I'm gonna pay for everything and have the party be a subsidiary of me, rather than the party being a year-round organization that the candidate can plug into. That's where we need to get back to. And that really should be the purpose of state parties. But they have become like the press arm or an extra fundraising arm for a candidate that then withers when that candidate goes away.”

You can watch that whole session here.

—On the same topic, it was nice to overhear Art Reyes, the founding executive director of Michigan’s We the People, say this while speaking on a panel on winning back factory towns, criticizing how much we focus on electoral campaigns: “We were building sand-castles, cycle by cycle. They were big and expensive but they were not ours and they were easily washed away. They were temporary and not rooted in our agency."

—During Netroots there was a protest of Meta, one of the conference’s Premier Sponsors, for having helped authorities in Nebraska prosecute a young woman and her mother for seeking an abortion; I wrote about that on Medium, as a jumping off point for discussing the challenge of being dependent on tech platforms that have gained quasi-governmental power over our lives.

Odds and Ends

—In Wired, Francesca Tripodi argues that people are trusting Google search too much for their political information and that the dominant search engine is feeding people more and more garbage than accurate info because of how it has changed its algorithms, damaging democracy in the process.

—Twitter’s former head of security is now blowing the whistle on the company, telling Congress and other federal agencies that it “has major security problems that pose a threat to its own users' personal information, to company shareholders, to national security, and to democracy,” according to CNN and the Washington Post.

—The Irish Council for Civil Liberties has filed a new lawsuit against Oracle, claiming the company has amassed detailed dossiers on five billion people.

—Telehealth nurses who used to be employed by Amazon tell the Washington Post’s Caroline O’Donovan why you don’t want to rely on Amazon Care.

—It’s too late to stop buying Tripp Lite surge protectors, but wow has rightwing movement organizer Leonard Leo won the dark money lottery.

I appreciate the Netroots comments about party building. I worked on taking over and growing my county party years ago. I was also a baby field organizer and turned down opportunities to go to other states to remain in my own backyard (NE Wisconsin). So while I was on the state party's payroll, which created the vehicle to fund a coordinated federal campaign, I was often in the field office located in my city.

When people walked in asking "how can I help" - something only done during Presidential years from my experience - I would hand them a membership card and say, "the best thing you can do is join the local Democratic Party." I did commitment calls to get people to attend the monthly meetings. The party exploded from less than 50 members to over 800, many of whom are still active today. I also made sure the volunteer list was shared to the local party instead of disappeared with the end of the campaign. In my opinion this is the greatest hinderance to local party building and it happens cycle after cycle ad nauseum.

The state party and campaign would have HATED what I was doing because it wasn't directly impacting my nightly numbers. But that core group of people gathered during that presidential cycle elected a state house member two years later, winning every ward in the district. and becoming the 1st Dem elected from the region in over a quarter century. Campaigns are not built to play the long game and they use the power of the purse to strong-arm the party and local committees to abandon long-term building strategies for short-term numbers. This is aided and abetted by overzealous regional field people, whom are often not from the area, and who withhold everything from local party activists because their loyalty is to the candidate, not the party, much less the local party. All of it is a clear case of fighting to win battles but contributing to losing the war.

I love canvassing and enjoy talking to people and more importantly, listening. This is the first time that I'm actually canvassing in my home district thanks to redistricting. I've had some delightful unexpected encounters, too. I knocked on the doors of our pediatrician, family friends, and my kids' classmates! Back to the heart of canvassing...Every interaction matters, even the ones in which voters are not on our side. There's so much to learn and absorb. Canvassing is about much more than politics and collecting data. It creates connections, strengthens relationships, builds community, etc. as you mentioned - all of which are valuable and powerful. Canvassing also affirms the humanity in all of us. There's always a good conversation that gives me hope, something to cling to - and that makes it all worthwhile.