Why Dems Keep Fighting the Last War

Turns out, there is a playbook. And it's filled with errors of commission and omission.

Dear readers: Today’s post is a deep dive in the belly of the Democratic establishment beast. If your main focus is the escalating challenge of ICE repression, just tuck this essay away for later and instead go to these links: ICE Rapid Response: State-by-state community-sourced info on how to connect with a rapid response team in your area. Go here if you need free 3D printed whistles or want to help pay for some. To donate to organizations on the frontlines in Minnesota, check out Stand With Minnesota’s list. And read and share this new and urgent Call to Action from Minnesota Organizers from Doran Schrantz.

Why do so many Democratic officeholders, candidates and political operatives keep following the same playbook, the one that says that if they want to win elections they have to raise tons of money, spend nearly all of it on targeted media, and appeal to middle-of-the-road voters by distancing themselves from liberal or left-wing positions, while saying nothing about the danger of rising fascism or elections in 2026 that may be neither free nor fair?

Why, for example, in this moment of deepening national crisis, with a major American city under violent attack by federal agents who have been told by their masters that they have absolute immunity from prosecution, and that city crying out for support as it prepares to stage a General Strike on Friday, are many Democrats saying little or, worse, pre-emptively advising their colleagues to reject the slogan “Abolish ICE” in favor of softer phrasing like “reform and retrain ICE”?

I don’t have the whole answer, and some part of it undoubtedly is explained by some combination of the age-old adage of “where you sit determines where you stand,” along with Upton Sinclair’s quip that “It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends upon his not understanding it.” If you’re a campaign manager or an elected representative, or someone who those people hire to help win elections, of course you’re going to keep applying expertise earned from past experience to the next election—even if we are no longer living in a normal, functional democracy. And if you’ve come up to your level of prominence by being good at writing, testing, producing and placing paid political ads, why wouldn’t you keep telling people that paid media is the most important tool in a candidate’s toolbox?

Still, it’s a bit startling to discover that there really is an actual written playbook that expresses the sum knowledge of today’s top Democratic political operatives, and that a new generation of campaign managers and candidates is being trained on it. I’m referring to something called the W.A.R. Room book, a 212-page manual that was recently leaked to me by a trustworthy source. It is primarily written by Aaron Strauss, Future Forward’s program director[1], in collaboration with a coterie of experts[2] drawn largely from the upper ranks of the top Democratic political committees and independent PACs (plus one political blogger named Matt Yglesias).[3]

“W.A.R.” stands for “wins above replacement,” a baseball term that Strauss and his colleagues have adopted as their way of describing someone who performs above their position’s baseline, which in electoral terms means getting a vote share above expectations. The existence of something called the “W.A.R. Room” itself is not a secret – it started as a post-2024 eight-week Zoom night school for mid-career campaign and political staff held in the spring of 2025, followed by a two-day in-person gathering in Washington, DC in early June. You can read about its core curriculum and see its list of trainers at War-Room.us. What you can’t see is the W.A.R. Room book, which is made available to campaign managers free of charge. I’m only going to quote from salient sections today, because a lot of people put serious work into this thing and it comes with strenuous requests about not sharing it publicly.

The copy I have is dated June 26, 2025, but this is meant to be a living document. Just last week, on January 14, the W.A.R. Room team convened several dozen people at the AFL-CIO building in Washington to tackle some fresh topics with the goal of adding new chapters to the book. Judging from a PowerPoint deck summarizing the meeting that I’ve seen, attendees at that meeting focused on four questions: “Popular economic ideas,” the impact of candidate quality and “authenticity,” how to inoculate candidates from Republican attacks on cultural issues, and an audience choice determined at the meeting, which turned out to be dealing with anti-system and less engaged voters. According to the real-time discussion notes recorded in that PowerPoint deck, the word fascism never came up. ICE was mentioned just once—this, a week after Renee Good was killed as part of “Operation Metro Surge” in Minneapolis, something that the vast majority of Americans have been paying close attention to. But I digress.

A decent chunk of the W.A.R. Room Book is innocuous. The bottom hundred pages or so is an almanac of national and state level political data aimed at giving readers a rough guide to baseline demographics for recent elections as well as how each congressional district voted in the last two presidential elections. Careful readers might quibble with relying on data that is skewed by US census undercounts of minority groups and that gives the false impression that each election occurs with the same, static electorate[4], but everyone relies on these numbers to get a ballpark view of the playing field. A short opening section on candidate recruitment and preparation starts by offering common sense advice about knowing one’s district and looking for potential candidates among people with real roots in the places they want to represent. A section on John Zaller’s model of public opinion and how to understand how campaign communications get incorporated by people into their voting behavior says nothing controversial about how people develop a world view and how hard it is to get a voter to pay attention to politics.

But the heart of the book is built around two flawed key assumptions and one gigantic omission.

The first assumption, one of the book’s “four strategic pillars” is that “Moderates over-perform.” Strauss writes, “Compared to extremists, candidates who are perceived as moderate and/or take moderate stances over-perform average expectations. This is true for both Democrats and Republicans. The explanation is straightforward: the median voter is a moderate.”

The second assumption is that today’s political war is entirely being fought inside an “attention economy” where the “media landscape is fractured” and “low-information voters are key” but where paid, targeted media is the most essential way of getting to them and the smartest thing to do is find out what these people say they like and then say it back to them. (Some call this “popularism”; Anat Shenker-Osorio more critically calls it “pollingism” and argues it traps Democrats into simply responding to revealed public opinion instead of trying to shape it.)

That leads into the gigantic omission. The book says almost nothing about having a field operation other than to mostly downplay its value, touts successes in places that have benefited from years of intensive community organizing without any recognition of its importance, and is completely silent on the dirty little secret of Democratic campaigning, which is that overreliance on the Democratic voter file causes campaigns to miss nearly ¼ of their potential voters and about 40% of potential Black, Brown and younger voters. (And then we wonder about post-election polls where those same voters disproportionately report that they never were contacted by a campaign.)

But let’s go ahead and see what in this wannabe bible for today’s Democratic campaign managers.

The Problem with Claiming Moderates Over-Perform

Before we can look at this claim, we have to see how the W.A.R. Room Book defines who is a moderate. It offers three definitions but only embraces one. Along the way, it goes through so many twists and turns that you’d be well within your rights to question if “moderate” is being used in a way that no longer means what you think it means.

A politician who tries to take the middle road on all issues—a “squishy, centrist”—is not the kind of moderate the playbook endorses, because, Strauss writes, “moderate voters usually have a mix of liberal and conservative views.” In that case, why not recognize that such voters are confused or volatile or multidimensional instead of sticking to a one-dimensional view of people’s political leanings? Strauss also rejects the notion that being a moderate means “siding with the establishment, status quo, corporations, or government systems.” He notes that confidence in America’s institutions is at an all-time low and many less-engaged voters have even less trust and tend to be conspiracy theorists. That indeed seems to be true, but how then are these people “moderates”?

It might be far more useful to talk about the many voters who do not fall neatly into the D or R boxes as “cross-pressured” rather than moderate, because they hold a mix of positions (think of Bernie Sanders voters who hate big corporations AND love their guns, or devout Catholics who oppose abortion AND the death penalty AND want increased social spending). Same with the many, especially younger people, who are self-identifying as “independents” and believe both parties are too subservient to their wealthy donors. Appealing to these sorts of voters may well be critical to the future of American politics, but trying to stuff all these people under the “moderate” label completely and uselessly flattens the picture. (However, if you’re trying to win an ideological war of intense interest to big Democratic donors, or give junior campaign managers the ability to project more confidence than they should…but I digress.)

Finally, we get to the kind of moderate the playbook wants candidates to emulate: someone who takes popular AND heterodox positions. Strauss writes, “The best path to moderation and over-performance is taking popular stances that are at odds with either the focus or substance of Democratic party orthodoxy. The research clearly shows that politicians who vote against the party (especially from the center) benefit electorally.”

Who are the Democrats who have done this well? Strauss points to Rep. Jared Golden of Maine who was the sole vote against a version of President Biden’s Build Back Better bill because it gave wealthy homeowners a big tax break, Rep. Marie Gluesenkamp Perez for attacking onerous day care food prep regulations, Sen. Ruben Gallego for being tough on border security, and failed Missouri Senate candidate Jason Kander for his ad showing off how he could assemble his army rifle blindfolded while touting his support for the 2nd Amendment and background checks.

These are all indeed examples of Clintonesque triangulation. But do you notice what aren’t examples of questioning the party orthodoxy? Voting against massive increases in the Pentagon’s budget to better fund domestic needs. Voting to suspend aid to Israel. Challenging Trump’s vicious attacks on immigrants and people of color. Opposing the crypto lobby. Etc.

It turns out that Strauss’ advice for candidates to distinguish themselves from the Democratic “orthodoxy” runs mainly in one direction. If the orthodox position is to only talk about “kitchen-table” issues—as the conventional wisdom ran last spring—and you’re Senator Chris Van Hollen and you go to El Salvador to highlight how the human rights of one of your constituents, Kilmar Abrego Garcia, have been violated, that’s not being what Strauss thinks of as a moderate. Which is too bad, because it turns out that such principled action not only had the effect of moving public opinion but it helped distinguish Van Hollen as a fighter rather than an appeaser. (Words that also do not appear in the playbook.)

To be charitable, one could say that the good thing about Strauss’ repositioning of the word “moderate” is that it rescues it from meaning things like “squishy, centrist, corporate Democrat” and replaces that with some anti-elite populism and cultural flexibility. But the case it reinforces for punching hippies (“extremists” is Strauss’ word) as THE way for Democratic politicians to appeal to cross-pressured swing voters is not helpful. Nowhere does the book examine how that affects traditional Democratic voters—many of whom are sick of being asked to back candidates who won’t fight for core Democratic values.

Do These Kind of “Moderates” Over-Perform?

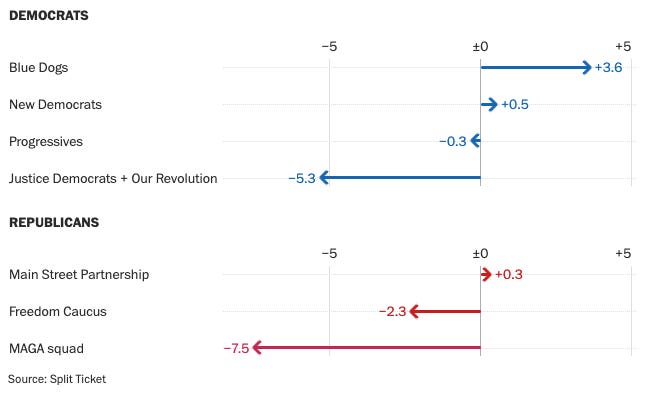

I don’t want to get too deep into the weeds here, as people far more expert than me like G. Elliott Morris and Adam Bonica have already done solid work on this front. A few main points to make. First, Strauss points to this study (gift link) by Lakshya Jain and Harrison Lavelle of Split Ticket, an election data analysis firm, as the “most useful depiction” of data from the 2024 election proving that moderates do better.

This suggests that House incumbents in the Blue Dog Caucus did better than expected in 2024 while Justice Democrats did worse. But are Blue Dogs NOT corporate Democrats or squishy centrists? Strauss doesn’t say. And are they benefiting from advantages that come from incumbency and/or not having mega-millions spent trying to damage their brand, as has been the case with “The Squad”? Strauss also doesn’t say. Bonica (with colleague Jake Grumbach) makes a more devastating critique of the Split Ticket analysis, arguing that the whole way it defines “wins above replacement” is broken. By his analysis, when you look at how Democrats performed compared to Kamala Harris in 2024, “moderates and progressives did essentially the same.”

The W.A.R. Room Playbook doesn’t address a different problem, which is how many “moderate” Democrats have lost in recent years while MAGA Republicans have won while pushing tax cuts for the rich and attacking Obamacare. As Bonica notes, “The Republican Party’s electoral success despite having one of the least popular policy agendas ever recorded suggests that traditional left-right policy and ideology aren’t driving election results.”

No matter, Strauss is convinced that, “The science is incredibly clear: moderates over-perform. Literally each of those links is to a different study that supports this basic finding.”

I’ve included the links from the playbook for those of you who really want to dig into the weeds growing in that sentence. Have fun. But do note: one study supposedly proving the value of being a moderate that Strauss links to is based on “a series of tests of the 1956-1996” elections. Not very relevant to today. Another finds that how well an incumbent fares in their election is only “modestly correlated” with their roll call votes. A third says that in general elections party labels do most of the work of helping voters decide who to vote for, while in primaries that lack such cues other information (such as group endorsements) matter more. A fourth says that the penalty congressional candidates pay for ideological extremism has declined since 1994. No kidding. A fifth says that Democrats who voted for health care reform paid a penalty in the 2010 elections. So Democratic moderates should back away from Obamacare? A sixth finds that “contested general elections [in state legislatures] have favored more-moderate candidates, on average. … However, this advantage is relatively modest in magnitude and appears to have declined noticeably in recent years.” The last link is to a study by Strauss of the 2022 elections and argues that Democrats who criticized teachers unions and “defund the police” did better than expected.

What does any of this have to do with the 2026 election, when the salient issues for voters will likely be some combination of: ICE killing American citizens with impunity, the implosion of NATO and trade war with Europe, measles outbreaks, a stock market crash caused by the AI boom or cryptocurrency shenanigans, and the list goes on. Your guess is as good as mine, but don’t worry: THE SCIENCE IS INCREDIBLY CLEAR. Just find a way to punch the left and you’ll do great!

The Problem with Chasing Low-Information Voters

The W.A.R. Room Book is not wrong to point out that today’s media environment is highly fragmented and voters, particularly those who are less interested in politics, can tune out and almost become unreachable (a number of platforms, including Netflix and Amazon, don’t allow political ads). It’s also not wrong to recognize that over time, people tend to forget political messages. But instead of getting curious about the places where Democrats have overperformed and exploring how years of concerted organizing created those environments, the book just stays under the lamppost where the light is brightest and urges readers to figure out how to “target its communication to the lowest-information voters who will still cast a ballot” since “paid media ads do persuade voters.”

What follows is page after page of advice on how to get earned media, how to cultivate reporters, the value of building a brand or slogan, plus lots of detail on all the different venues for paid advertising (linear television, streaming, YouTube, Meta, radio, podcasts, apps, direct mail, paid canvassing, and paid influencers). The best time to run ads, Strauss writes, is in the last week before an election, but he also suggests doing so earlier if an ad will “prove viability for fundraising” or “to fundraise from voters.” If you’re doing the former, he says, “it might be a good idea to both (a) run advertising for a short period of time, and (b) commission a poll to be run at the tail end of the buy. Put the poll in the field while the advertisements are still running so that ad effects can’t decay at all. Take the ads down right after the poll is complete.”

And to think that last week at the W.A.R. Room meeting I mentioned above, a top focus was figuring out how to help candidates with their “authenticity.” Maybe, just maybe, the way to win more tough elections is by addressing the conditions in those districts that make them “tough” in the first place?

Why So Silent About Organizing?

That gets to the last major problem I have with the W.A.R. Room Book: how diligently it ignores the effect of power-building on electoral outcomes. This is especially curious given that it opens with a glowing introduction from Rebecca Lambe, who built Senator Harry Reid’s formidable political machine in Nevada. As she writes, “My mentor, the late Senator Harry Reid, a former boxer, taught us how to fight—and how to win... Reid also believed in building power from the ground up. His legacy in Nevada proves what’s possible when smart campaigns are powered by real people and real purpose.” Lambe also talks about working with “Senate candidates who started out unknown, outspent, or underestimated—and watched them defy the odds. Their victories weren’t accidents. They were the result of grit, smart strategy, and relentless organizing.”

These candidates must include people like Jon Ossoff and Raphael Warnock of Georgia and Mark Kelly of Arizona, places where “relentless organizing” set the table for game-changing wins, in part by enabling big voter registration drives and in part by shaping the issue environment in those states. But Strauss & crew say nothing further about the importance of this work, instead taking as a given that we somehow must go from zero to 100 in each election cycle solely using political marketing tactics. The fact that top party operatives make this assumption every two years compounds the problem of the Democrats’ shrinking organized base.

Harry Reid’s political machine was built on a year-round community presence (not campaign-season contact), strong partnership with the state’s power Culinary Workers Union (providing deep integration with its working-class Latino community); trusted validators developed over years (not weeks or by purchasing “influencer” attention); service provision (help with immigration paperwork, job applications) and old-fashioned relational organizing (friends talking to friends within trust networks). Reid made the word Democrat in Nevada mean something like “the people who show up for us.” It’s not rocket science, but it is hard work.

Given how much the playbook dwells on the importance of low-information voters and how hard it is to reach them with targeted ads, one would think that developing non-advertising-based pipelines to such voters would be a higher priority. That would include investing in developing trusted messengers (friends, family, coworkers, community figures), building relationships in non-political contexts (churches, union halls, barbershops, child care centers, youth sports), repeated contact over years (not just a last-minute blitz), material aid, and cultural presence. Gosh, it might even include fighting for some big-picture things that could dramatically improve people’s lives (or save them from corporate predators and rightwing thugs) enough that such voters would feel a bigger stake in politics rather than being alienated by political moneyball.

But what do I know? I’m just a guy living at the tail end of what these top Democratic political operatives push through the body politic. It keeps repeating and what comes out ain’t pretty.

[1] In case you’ve forgotten, Future Forward is the giant super-PAC that raised and spent $700 million on paid media meant to support the Biden and then Harris presidential tickets, saving most of that money for the last weeks of the election because it believed that was when it would be most effective, and which is now apparently advising many Democratic big donors to hold their gunpowder and not run attacks aimed at driving down Trump’s popularity over his chaotic presidency and to stick to kitchen-table issues. Though Strauss works for Future Forward, the introduction to the W.A.R. Room book notes that it is “not a Future Forward product.”

[2] The full list of contributors to the W.A.R. Room book:

Abby Curran Horrell: Executive director of the House Majority PAC, 2019-present

Jon Fromowitz: Cofounder, Future Forward (previously, senior adviser for paid media for Biden 2020)

Todd Harris: Managing director, Blue Rose Research

Adam Jentleson: President, Searchlight Institute

Brad Komar: Senior advisor, House Majority PAC, 2019-present

Rebecca Lambe: Founder/senior adviser Senate Majority PAC, Senior adviser, Cassidy & Associates lobbying firm

Ty Matsdorf, Partner, The Messina Group; former director of the DCCC’s independent expenditure program, former campaign director of Senate Majority PAC

Matt Morrison, Executive director, Working America

Kristen Orthman, Democratic communications strategist; Former director of communications, DNC

Ishanee Parikh, Creative director, Future Forward USA (2020-present)

Jim Pugh, CEO ShareProgress 2013-present and Director, AI Progress Hub

Ausaf Qarni: Director of research and analytics, Working America

Meg Schwenzfeier: Chief Analytics Officer, Harris for President

Taren Stinebrickner-Kauffman: Founder, AI Impact Lab

Matthew Yglesias: Writer, Slow Boring

Jesse Ferguson: General consultant and Democratic Strategist, Dover Street Strategies

Kelly Ward Burton, Founder & CEO, Both/And Leadership; Former executive director, DCCC.

Megan Clasen, Partner, Gambit Strategies

Patrick Bonsignore, Director of paid media, Biden for President, 2019-2024

[3] Simon Bazelon, Kelly Ward Burton, Christina Coloroso, Kevin Collins, Kass DeVorsey, Andrew Grunwald, Daisy Hernandez-Barguiarena, Josh Kalla, Leo Liu, Jonathan Robinson, Anat Shenker-Osorio, Gaurav Shirole, David Shor, Madeline Twomey, Margit Westerman, and Miya Woolfalk are also thanked for reviewing the book in advance, and David Plouffe, Ben LaBolt and Rep. Marie Gluesenkamp Perez are thanked for providing supplemental videos.

[4] Former AFL-CIO political director Mike Podhorzer says, “The Electorate Is Never the Same River Twice. The ‘median voter’ image wrongly suggests that both parties have a certain percentage of base voters baked in, and that the contest is about which party can persuade more middle-of-the-road swing voters to join them and secure a majority. This image presumes what I call a “Flatland” mental model, in which the pool of voters stays basically the same from year to year. In the reality of “3-D Land,” however, we know that churn in the electorate is what matters most – which kinds of voters decide to stay home instead of turn out to vote, or vice versa.

Follow the money. One of the biggest problems, hinted at here, is the amount of money in politics. Not just because of the time and soul-selling it takes to raise it, and the influence it can buy, but with how it’s spent. There is an entire industry of consultants who suck up that money developing “messaging” and running ads. They sell manipulation not real communication and empathy. How do you make money on the hard work of folks getting out in their neighborhoods building real relationships? You don’t. Stop listening to these consulting firms and get your ass into your neighborhoods. This book you so wonderfully pull apart is actually just an advertising packet for these leaches.

Thanks for the glimpse into the belly of the beast. The playbook has all the excitement of soggy, cold, plain noodles.

You saved the best for last - your suggestions: "...investing in developing trusted messengers (friends, family, coworkers, community figures), building relationships in non-political contexts (churches, union halls, barbershops, child care centers, youth sports), repeated contact over years (not just a last-minute blitz), material aid, and cultural presence..." and, "...fighting for some big-picture things that could dramatically improve people’s lives (or save them from corporate predators and rightwing thugs) enough that such voters would feel a bigger stake in politics rather than being alienated by political moneyball."

Maybe instead of hunkering down in a conference room with calculators and legal pads and spreadsheets (the cover illustration for the article was pretty good!), the democratic brain trust should've been on the streets of Minneapolis handing out hot chocolate. I guess we'll find out in November...